On 17 July 1917, the London Gazette published a proclamation by George V:

We, out of Our Royal Will and Authority, do hereby declare and announce that as from the date of this Our Royal Proclamation Our House and Family shall be styled and known as the House and Family of Windsor, and that all the descendants in the male line of Our said Grandmother Queen Victoria who are subjects of these Realms, other than female descendants who may marry or may have married, shall bear the said Name of Windsor.

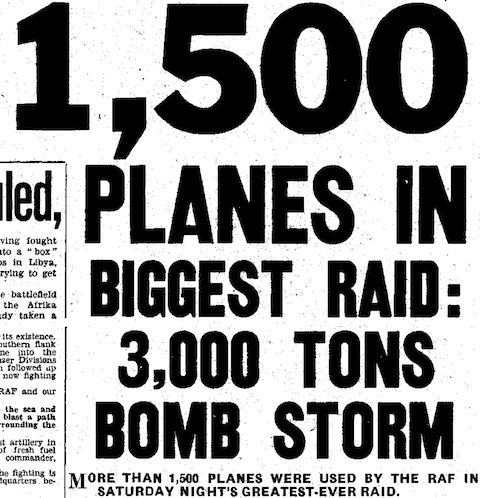

Now, this was only ten days after the second Gotha raid on London, and just over a month after the first Gotha raid. These air raids took place in broad daylight with little interference from British air defences, and between them killed more than two hundred people, including eighteen children at the Poplar Infants School. One result, eventually, was the Royal Air Force; a more immediate one was anti-German rioting in several London suburbs. What I've often wondered is whether the House of Windsor was another result, because before the proclamation of 17 July it used to be known as the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Did the Gothas kill the Saxe-Coburg-Gothas?

The Wikipedia article on the House of Windsor does seem to imply that this was the case, but we can do better than Wikipedia. Ian Castle says:

The [7 July] raid brought a wide variety of reactions. Sections of the bombed population turned against immigrants in their midst, considering many with foreign names to be 'Germans'. Riots broke out in Hackney and Tottenham where mobs wrecked immigrant houses and shops. Moreover, such was the anti-German feeling that four days later King George V (of the Royal House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha) issued a proclamation announcing that the Royal family name had changed to Windsor.

Similarly, A. D. Harvey writes:

Ten days after the air raid King George V changed the family name of the royal dynasty from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor -- the fact that German heavy bombers were also called Gotha was an unfortunate coincidence which obviously could not be allowed to persist [...]

And likewise Ian Beckett:

[After the Gotha raids] There were riotous assaults on allegedly German-owned property in the East End and the affair not only played decisive role [sic] in the establishment of the Smuts Committee -- and, therefore, the ultimate creation of the Royal Air Force in April 1918 -- but also persuaded King George V to change his dynastic name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor.

So there are histories which claim that the Gotha raids played a significant and perhaps decisive role in convincing the monarchy to drop the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha name. But all of these discussions are quite general, and none quote any primary sources on this point. Moreover, they are all by military historians, for whom (like me) it might be obvious to look for such a connection. Unfortunately, more detailed accounts, written by historians of the monarchy, do not seem to back them up. In particular, it looks like the search for a new name for the Royal Family began before the Gotha raids took place.

...continue reading →