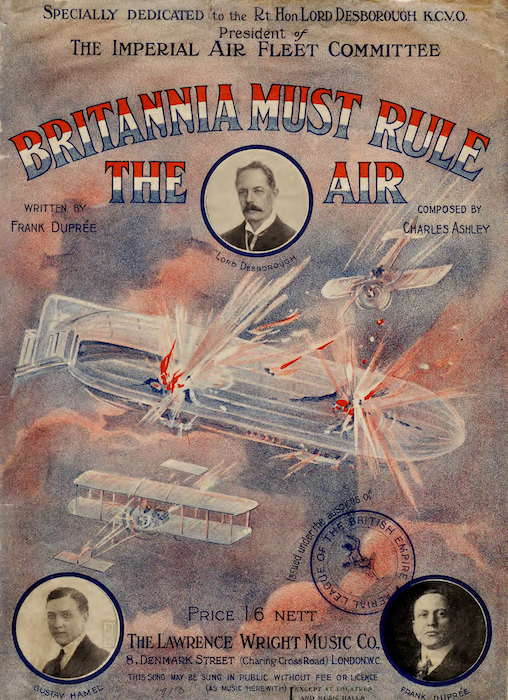

Britannia must rule the air!

This stirring scene is the cover for the sheet music for a song published in 1913, Britannia Must Rule the Air, written by Frank Duprée and composed by Charles Ashley. It shows a reasonable (if stubby) approximation of a Zeppelin in the process of being destroyed by gunfire from two aeroplanes, a Farman-type biplane and […]