[Cross-posted at Society for Military History Blog.]

In Giulio Douhet and the Foundations of Air-Power Strategy, Thomas Hippler describes what he calls Douhet's 'ahistorical historicism':

His thinking is ahistorical to the extent that it poses a concept of history ('everything has changed') that simultaneously cuts off history itself. His thinking is historicist, because this absolute beginning not only occurs as a break within history, but also to the extent that it gives way to a technology-driven teleological understanding of later historical development. In other words, it gives way to interpreting the development to come in the sole light of the imagined essence of this beginning.

That is, Douhet asserted that warfare in the future is going to be utterly different to warfare in the past, and that we can only predict it by looking at warfare in the present, which itself does not resemble warfare in the future either.

Douhet, of course, was not alone. Airpower prophets routinely asserted that the past was no guide to the future, and that the present was not much better, but it was all there was to go on. So Claude Grahame-White and Harry Harper wrote in 1917 that

In viewing the lessons of this war, as they are likely to throw light on the future of the aeroplane, either as a vehicle for transport or as a weapon, it must be understood that this campaign by air, in the sequence of its phases, offers little or no guide to the trend of an air war of the future. The next great war, should it come, will begin where this leaves off; and all its subsequent stages, so far as any one air service is concerned, must be governed by the success or failure of that service in its first offensive by air -- an offensive which, following instantly on a commencement of hostilities, will need to be delivered with a maximum possible force and speed.

The paradox is that as the last war receded and the next war, presumably, approached, airpower prophets had to continue to rely on that last war for their evidence, as it was the only example of large-scale application of airpower to date. Their futurism became increasingly historical, in other words. To take a random example, in 1937 Frank Morison devoted three quarters of his book to recounting the experience of London and Paris under aerial bombardment two decades previously, and the final quarter to showing how this experience gave only a hint of what was to come. Recalling the 'hectic days of excitement and warlike preparation' before the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914, he suggested that

Surely few historical parallels could be more misleading, because the march of science has destroyed in advance that indispensable time-lag upon which the successful deployment of our military, social and industrial resources mainly depended.

The reason, of course, was the march of technological progress:

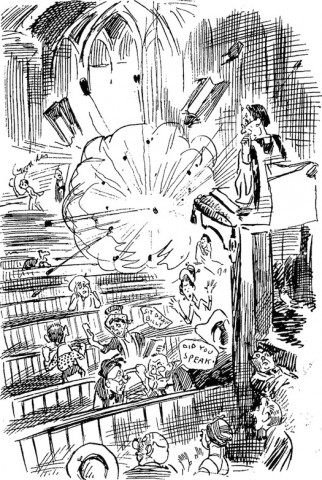

It is practically assured that the speed of a long-distance bombing squadron, sent against London in the next war, will not be less than 250 miles per hour and may conceivably be in excess of that figure. This means that a formation sighted at Beachy Head, say at 11 a.m., if not intercepted and driven off, will reach the suburbs at 11.12 a.m. and be over Central London about one minute later.

Hence the teleology, with war, and thus all of history, marching towards its inevitable fate of domination and even determination by the bomber. Of course Morison was not to know that within a couple years Beachy Head itself would be the site of a Chain Home Low radar station, and hence part of the solution to the bomber threat. But then, by definition believers in the bomber never had faith in the fighter.

Douhet, Grahame-White, Morison and the rest were essentially military mini-singularitarians. According its adherents, the Singularity is the point in the not-too-distant future when technological changes, especially in artificial intelligence, will accelerate and converge such that they will so utterly change society and humanity itself that it will be practically unrecognisable. But like the airpower prophets before them, singularitarians like Ray Kurzweil extrapolate wildly from the past -- CPU speeds, increasing lifespans -- to predict that the future will be nothing like it -- uploaded personalities, immortality. They too are ahistorical historicists, and if the past is any guide to the future, just as likely to be right.