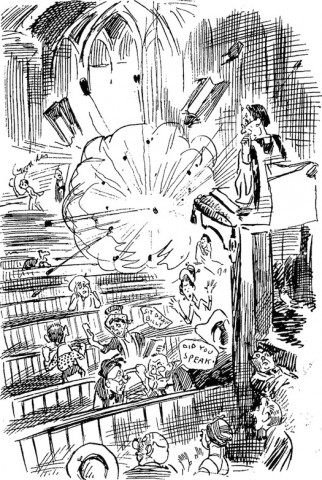

For a country so far from the frontline, there was a surprising amount of discussion in the New Zealand press in the autumn of 1918 about the possibility of Auckland being bombed or Wellington being shelled. It's true that it was often framed in a joking fashion, as with the above cartoon which appeared in the New Zealand Observer on 4 May with the caption 'IF A BOMB FELL ON ONE OF OURS?' showing the reactions of an amusingly confused congregation as the war intrudes into their Sunday devotions.1 But despite the humour, there's an undercurrent of fear, and also perhaps, strangely, of desire.

So, according to the Observer's 'They Say' column on 30 March, one of the things they were saying was

That is is possible that a raider will visit New Zealand, let loose an air plane, and drop bombs on Auckland City. If one should drop on Laidlaw Leeds? Good-bye New Zealand.2

Laidlaw Leeds was a big Auckland department store (now better known as Farmers); obviously it's an exaggeration to suggest that blowing it up would be an irretrievable disaster for the country as a whole. It's just part of the sarcastic and cynical style of the columnist. A few days later, a similar column in the New Zealand Free Lance (quite possibly inspired by the Observer, its sister paper) suggested that 'town talk' had it

That if a Hun air-raider should visit this fair Dominion and drop bombs on some of our 'indispensables' it would be 'Good-bye, New Zealand.'3

The 'indispensables' here would be men deemed too essential for the war effort to be conscripted. What's significant about these jokes is that the idea of German raiders launching aeroplanes to bomb New Zealand cities had some currency, otherwise there would be no point to them. Another 'They Say' comment in the Observer a couple of weeks later made the connection to the mystery aeroplanes scare explicitly:

Thousands of New Zealanders have seen hostile aircraft in New Zealand air lately. It is sincerely hoped they will not drop bombs on any 'indispensables,' or even on Appeal Boards.4

How far this claim of 'Thousands of New Zealanders' seeing mystery aeroplanes can be trusted is unclear. Again, the jocular tone of the column means it can't be taken at face value, as another relevant entry from the same issue shows:

Owing to the reported presence in New Zealand of hostile skycraft hairdressers are secretly planning punitive hair raids.5

Presumably, hairdressers were doing no such thing! But it seems likely that, at the very least, 'Thousands' can be read as indicating that many more mystery aeroplane sightings took place than were otherwise reported in the press.

It wasn't just about aeroplanes, however. Recall the apocryphal Aucklander who was worried about bombs dropped from seaplanes as well as:

[...] these big guns firing 100 miles. What's to stop a raider coming in behind Rangitoto with one of these guns and firing a shell into our houses in Grafton Road?6

This is a clear reference to the Paris Gun, a German supergun which fired over three hundred 9-inch shells at Paris from a distance of 120 km, beginning with the opening of the Spring Offensive on 21 March. Unlike Gothas (which also raided the city during this period), the Paris Gun gave no warning: the shells could land anywhere at anytime. They killed 256 civilians in total, 88 alone when a shell hit the church of St-Gervais-et-St-Protais on Good Friday -- an incident prominently reported in the New Zealand press.7 This deadly, surprising, and above all long-range attack on Parisian churchgoers seems to have struck a nerve on the far side of the world, and was conflated with the concurrent fears of a attack on New Zealand by a raider.8 For example, the caption of the cartoon at the top of this post actually read in full:

IF A BOMB FELL ON ONE OF OURS?

Parson (reading war news). So a shell from the Hun long-distance gun fell onto a church and killed and wounded hundreds of people? 'Um, safer here.9

There are several things going on here. One is a commentary on the lack of churchgoing in New Zealand, as yet another 'They Say' item from 30 March makes clear:

The remarkable thing about the German shelling of Paris is that when the shells hit churches they invariably injure someone. Now if a shell were to fall on a New Zealand church ---10

Another is the obvious one, the simple act of imagining New Zealand under fire. And I think that yet another is the confusion of the congregation, who are surprised and don't know how to interpret the explosion: 'Did you speak?', 'Sit down Billy!', 'Good day'. That is to say, that New Zealanders, so remote and safe from the fighting, don't know what war really is.

This is where desire comes in. Early on in the mystery aeroplane scare, the Observer published a letter from a wounded New Zealand soldier who had been in London during an air raid. He suggested that

Except for the unfortunate few who are killed, I think it is a good thing there is a raid now and again. It lets some of these headed [sic] 'peace at any price people' in the House of Commons see that there is really a war on, and it would do both Australia and New Zealand a lot of good, too, to get either a good raid or a bombardment on to some of their main cities. It might shake some of those blighters up who are hanging back, and probably -- having had a taste of what the gentle Hun is really capable of doing -- they would perhaps have a little more real fellow-feeling for the maimed and wounded who are lucky enough to get back to their native shores, after being under the iron flail for months -- perhaps for years.11

This was exactly the same discourse that was evident across the Tasman at the same time: that it would do Australians some good to have some bombs dropped on them. While this didn't happen, both Australians and New Zealanders did start dreaming war, by seeing hostile aircraft in the skies.

Interestingly, a leading article in the Observer on 6 April seemed to suggest that the scare over mystery aeroplanes, German raiders and Paris Guns was not about dreaming this war, but rather was about dreaming the next war, apparently with Japan:

There are local signs from people who have never seen war, and have never lived on a frontier with shells of war, that they have got the 'wind up.' It is to be remembered that we are many thousands of miles from the gun that is set up to kill Parisians, and that there is no credit in being either optimistic or courageous so far away. But to those people who are getting 'the wind up' one would say, as one has said so many times before, that New Zealand its very self will sooner or later become the same sort of a cockpit as Belgium, and that the courage of civilian New Zealanders will enhance in the same proportion as her danger increases. It is said by those who understand the signs that the Pacific will yet become the battle ground (or sea) for humanity.12

There follow references to a recent controversy over the future status of Samoa, leading to the question of whether the sort of person who 'only shoots off his mouth' about war will 'shed his own blood for New Zealand when New Zealand is a frontier, and the enemy is battering at its gates? -- not the gates of Paris, but of Wellington and Auckland'.5 The aerial threat appears in the next paragraph:

People living on frontiers always expect war, and insular people always affect to believe that islands are impregnable. There is no impregnability anywhere, for the rapidly developing sky battle machine has altered all that, and the enemy has even invaded England, if persistent air raids can be called invasion. What is possible in the method of attack on England is also possible as far as little New Zealand is concerned. Every ounce of war effort made by New Zealand has, of course, been in the direction of sending men out of the country, and not in preparation for the defence of this country -- a defence, by the way, that will have to be naval. In the future the discipline of the people will have to be of a sterner kind if New Zealand is to be held by New Zealanders, and by every known means the State should instil into the people a knowledge of the possibilities. Everyone should be told in the plainest terms that New Zealand is not to be immune from war. When her time of trial comes may New Zealanders, with the philosophy of Jean, say, 'C'Est la guerre!'5

The leading article ended by predicting that

New Zealanders will have to grit their teeth harder and make a better do of it if the country is to remain British, and look forward to a day when, with shells falling in Queen Street, the citizens calmly exclaim, 'Why worry -- "C'Est la guerre!"'5

Did New Zealanders really have the wind up? After all, only a handful of mystery aeroplane sightings had been reported in the press. And nearly everything discussed in this post is either couched in humorous terms, and is from the one newspaper. So it could be a bit of a beat-up. Indeed, after late April, even the sorts of half-joking reports of mystery aeroplanes I discussed previously disappeared.

But only for a while. In the next post in this series I'll examine the re-emergence of the scare at the end of May 1918. And finally I'll look at the evidence for the government's response to the mystery aeroplanes.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- New Zealand Observer (Auckland), 4 May 1918, 5. [↩]

- Ibid., 30 March 1918, 7. [↩]

- New Zealand Free Lance (Wellington), 4 April 1918, 22. [↩]

- New Zealand Observer, 13 April 1918, 7. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Ibid., 20 April 1918, 16. [↩]

- E.g. New Zealand Herald (Auckland), 1 April 1918, 5. [↩]

- Compare another item from the 'They Say' column about how Aucklanders wouldn't mind something like a Paris Gun to hit Parliament House with: New Zealand Observer, 30 March 1918, 7. [↩]

- Ibid., 4 May 1918, 5. [↩]

- Ibid., 30 March 1918, 7. [↩]

- Ibid., 16 March 1918, 11. [↩]

- Ibid., 6 April 1918, 2. [↩]

Pingback:

The mystery aeroplane scare in New Zealand — V

Pingback:

The mystery aeroplane scare in New Zealand — IV | Airminded