A recent post at Ptak Science Books alerted me to the existence of page 363 of the Illustrated London News for 6 September 1913. Not that I was surprised by this in general terms, but I was unaware of what was on it: an artist's impression of a both a flying aircraft carrier -- which idea I've discussed before -- and an airship drone -- which I haven't.

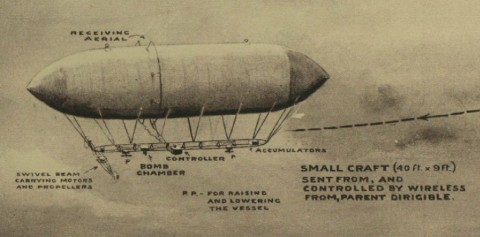

As the images above and below show, the idea was that the 'parent dirigible' (which looks very much like a Zeppelin) would carry several of these 40-foot long 'crewless, miniature air-ships' slung underneath it, and then launch them when in range of a target (here a fortification). The smaller airship would then be controlled by radio to fly drop its bombs 'on any desired spot'.

...continue reading