The 'flight' -- The machine reached the edge of the slope, shot out a few yards into the air with the impetus it had acquired, and then dropped with a crash onto the rocks.1

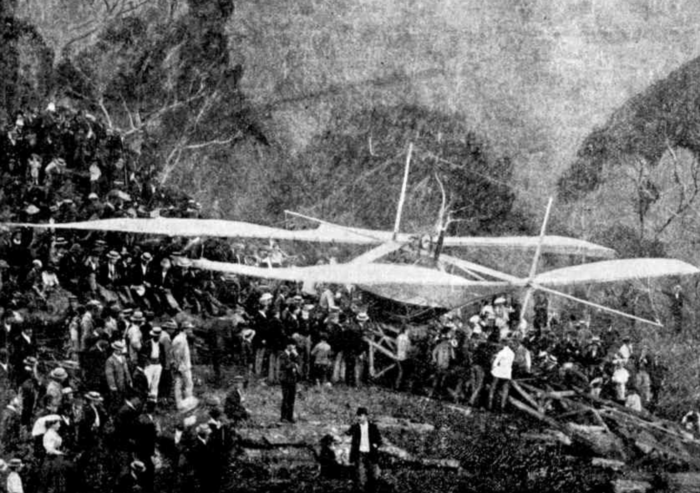

I am very nearly done with N. R. Gordon, who built at least five completely unsuccessful flying machines over a period of several decades, from well before Kitty Hawk to after the First World War, when how to fly was pretty much a solved problem. But a post at the Aerodrome alerted me to the existence of some further photographs of his first and most ambitious attempt, before a large holiday crowd at Chowder Bay on Boxing Day 1894. The most remarkable is the one above, which shows Gordon's oddly sinuous machine just at the moment of being launched over the precipice. In the background there are many small boats out on the bay, and in the foreground eight or nine people with their backs to the camera, watching the flying machine. All the accounts frame the trial as a failure -- or worse, as I'll come to -- but at this very instant the possibility of success was still there. Did these spectators believe, or hope, that they were witnessing the beginning of the conquest of the air?

Inspecting the wrecked machine -- The 'boiler,' still smoking, is seen in the background.2

In this one, though, the failure is complete, though the wreckage still affords some entertainment. The two men in bowlers at the right seem to be smirking (though that could be my imagination).

Oddly, the source for these photographs is from a British magazine, Wide World Magazine, some fifteen years after the event.3 I'm not sure why there was any interest in an obscure attempt at flight in another hemisphere and another century, except that in 1909 aviation was highly topical but still highly fraught, and it was perhaps easier to sneer at aeronautical foibles at such a remove. And this article does sneer, portraying Chowder Bay as a hoax perpetrated by a conman on a naive public.

Chowder Bay, Sydney Harbour -- 'Dark' undertook to fly his machine across this stretch of water to a point some miles distant.4

The author of the Wide World Magazine article is J. S. Boot, who I haven't been able to identify but appears to be Australian or at least familiar with Australia. But whether or not the author was present at Chowder Bay, the account he or she has written is problematic. For a start, Gordon, the supposed conman, is not mentioned at all. Instead, possibly for legal reasons, the inventor is named as Richard (or Dick) Dark. Dark is said to have come from Queensland, which fits what I can find of Gordon (who seems to have emigrated to Brisbane before he went to Sydney); and is described as having the gift of the gab, which sounds like Gordon too. I can't say whether it's true that Gordon's 'chief sphere of activity had been confined to the various hotels and saloon bars of the town'; it could well be, but a suggestion of drunkenness was a standard way of smearing somebody's character at this time.5

But when Boot says that Dark 'admitted freely that he had never yet attempted anything in this line' of aeronautics, that seems to neglect the fact that nearly a year and a half before Chowder Bay Gordon was experimenting with an earlier model of his ornithopter. His persistent experimentation later in life with flying machines shows him to have been sincere, if misguided, in his attempts to build a flying machine. (Boot doesn't mention any of these, even though the flight trials at Footscray took place just two years previously and could have been worked into the same scam narrative quite easily.)

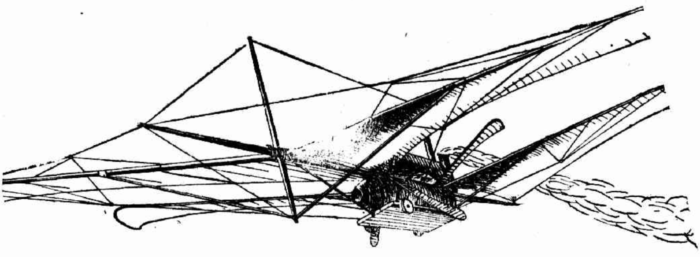

The machine almost ready for the trial trip -- Notice the inclined way down which it was to glide.6

More significantly, Boot places Dark at Chowder Bay, overseeing the construction of the machine and superintending the flight attempt, but then taking off with the takings afterwards:

The last the people of Sydney saw of Dick Dark was a swiftly-moving buggy on the sky line, and their appreciation of his genius was hardly helped by the quickly-acquired knowledge that not only had he eloped with the whole of the gate-money, but had left behind him a souvenir in the shape of a big unpaid bill for the cost of building the flying machine, erecting the staging, and the wages of the workmen he had employed!2

But contemporary press accounts, even though they are quite scathing of the Chowder Bay 'fiasco', don't mention this absconding with the funds at all. Nor do they mention Gordon, or even anyone who sounds like an inventor, as being there on the day. Gordon himself claimed afterwards that he had not been associated with the trial for a couple of weeks before the flight attempt.

Just before the start -- The boiler, concerning which the 'inventor' maintained a great deal of mystery, is seen in the centre, covered with matting.6

It's tempting to write off Boot's account itself as a complete fabrication, if not libel. But the idea that a failed attempt at flight must be a hoax perpetrated upon a trusting public, rather than something to be expected given flight's infancy, was a persistent one, as I previously discussed in relation to balloon riots, including the one in Sydney in 1856. And some of this sense of moral indignation comes through in Boot's description of the crowd's behaviour at Chowder Bay. Firstly, and this does accord with other contemporary accounts, at the lack of a flight attempt at all:

The flying machine, however, did not rise at the appointed time, and as Dick Dark and his assistants were still actively at work on the fittings it was evident that some delay had occurred. The boiler, too, which was now in position, was still covered with matting, and the sporting element among the crowd began to lay odds against the chances of a successful flight. An anxious hour went by, and the flying machine still remained at rest. The spectators began to get restless and a little out of hand, several ugly rushes taking place towards the centre of the ground. The local roughs, known as the 'Chowder Bay Chickens,' were quick to take advantage of the situation, and when the Australian larrikin starts out to make himself objectionable he does so with a whole-heartedness that is bad for anything breakable in his immediate neighbourhood. Consequently it looked as though the flying machine, if it did not achieve fame in the air, would surely meet with an untimely end on earth at the hands of 'the Chickens.'

Thanks to the disturbing influence of these gentlemen a riot was soon imminent, but fortunately, just as things were beginning to look serious, it was seen that a thin streak of smoke was issuing from the boiler, and a tremendous cheer was raised at this belated sign of life.7

And then again after the crash, when it seemed that the flying machine was no machine at all:

Most of those present had been inclined to condole with Dick Dark in his misfortune, but when a short examination revealed the fact that the mysterious boiler was nothing more nor less than a hollow iron drum containing a mass of burning bracken, which had produced the smoke, and that the machine was innocent of anything in the way of mechanism for propelling purposes, and consequently absolutely incapable of aerial flight, his much-advertised invention at once presented itself in a new and totally unexpected light. In fact, the flying machine, to all intents and purposes, was a bare-faced 'fake.'

Then it was that a pretty general feeling arose that this too-enterprising gentleman justly merited some swift and sure form of retribution as a fitting reward for his duplicity. Up to that moment, however, the fact that he was more conspicuous by his absence than anything else had, in the excitement, escaped notice, and a hunt about the grounds failed to reveal his whereabouts.2

Leaving aside the accusations of fraud and unpaid wages -- of which I am sceptical, at least as far as Gordon is concerned -- if there is any truth to these accounts of crowd emotions then there's also a tension. The restlessness as the boiler gathered steam suggests a desire for entertainment, which is fair enough: they'd paid their shilling(s) and they wanted their fun. But then why the anger over the fake flying machine? They'd had the show they came to see (and presumably few people actually believed with certainty that they were going to see the world's first true flying machine soaring out over the Heads). It seems that even though the spectacle here was acknowledged as entertainment, it also needed to be authentic, plausibly aeronautical as far as popular understanding was concern. When that belief was broken, anger over the abuse of the larrikin's trustworthy nature was the result. Flight or fight, then.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- J. S. Boot, 'The Sydney "flying machine"', Wide World Magazine, April 1909, 32-36, at 35. [↩]

- Ibid., 36. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- In another Australian connection, Wide World Magazine also published 'The Adventures of Louis de Rougemont', a supposedly factual account by a Swiss explorer who wrote that 'I knew that wombats haunted the islands in countless thousands, because I had seen them rising in clouds every evening at sunset'. [↩]

- Boot, 'The Sydney "flying machine"', 33. [↩]

- Ibid., 32. [↩]

- Ibid., 34. [↩] [↩]

- Ibid., 35. I can't find any mention of the 'Chowder Bay Chickens' in Trove, but other accounts did refer to the 'Push' being present. [↩]

Martin

It does seem rather sad, that for all his years of trying, Gordon never did succeed in building something that did actually fly, even after so many others had done so (in the case of his Kangatross).

I'm not sure his seemingly eternal optimism is a case for celebration or not, but I guess he does fit the bill for being 'airminded'.

Brett Holman

Post authorYes, it is a bit sad! I suppose he's representative of a horde of other airminded inventors who had an idea about how to fly, perhaps just a bit more single-minded. Most, like him, never got anywhere -- but a very few did (and that's all we needed).