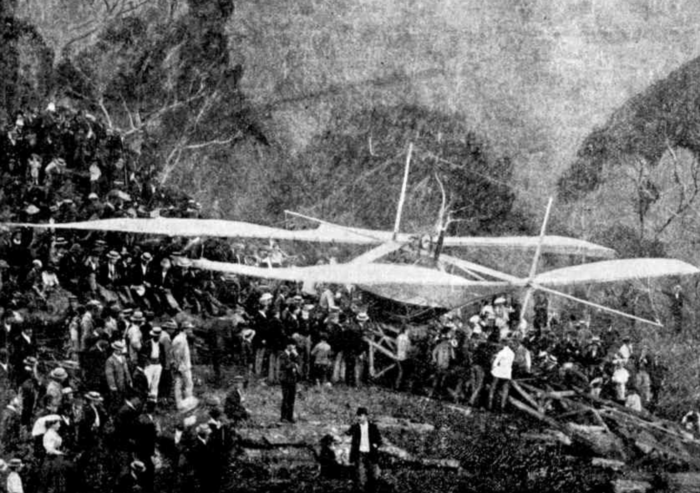

When we first met N. R. Gordon, it was in Sydney in 1894 and he was preparing a steam-powered ornithopter for flight. When we last saw him, it was 1900 and he was filing a patent application for a human-powered ornithopter. Here he is again, in May 1907, this time at Footscray in Melbourne’s west, attempting another ‘experiment with a flying machine’:

The body consisted of a small canvas boat on two pneumatic-tyred wheels, and had four great white canvas wings, each 17ft 6in in length. The flying machine was hitched on by a rope to a motor car, which, when all was ready, set off at full speed. The flying machine, which carried no passengers, of any kind, rose gradually about a foot from the ground, but when apparently about to soar off to the sky the wings carried away, being too fragile to stand the strain.1

I think that is the machine pictured above, which has the tires though maybe not a ‘boat’2 It seems quite different to the Chowder Bay machine, chunky rather than spindly.

In any case, Gordon was soon back with a bigger or at least more expensive model, funded by the grandly-named Footscray Aerial Navigation Syndicate (estimated at £300 in May, though it’s not clear how much it ended up costing).3 In August he was at Maidstone (not far from Footscray) with ‘a grotesque object like a boat with wings, but which in reality was reputedly a flying machine designed to revolutionise the modes of travelling […] The contrivance consists of a small boat with two masts, to which is attached four wings of sail canvas’.4 This was again towed behind a car,

But the machine absolutely refused to fly. The motor put on full spead ahead, the

eight strong men, holding up the wings, manfully struggled along, anon splashing into mud holes; the inventor, in his shirt sleeves ran in the rear, endeavoring at the same time to lift the apparatus from the ground, and behind them all came a mob of amused spectators, who voted it the funniest sight that had ever been witnessed out that way. Those under the huge wings were yelling with might and main to the driver of the motor car to stop; the crowd cheered him on, and the crowd could be more clearly heard and seen, with the result that the perspiring flying machine bearers were almost exhausted before the car was brought to a standstill.5

If this account verges on the farcical, that of Gordon’s third trial that year (possibly written by the same journalist) is even more so, under the headline ‘FOOTSCRAY “FLYING” MACHINE. A MIRTH PROVOKING INVENTION’:

Despite efforts to preserve the utmost secrecy, there was a large, gathering of residents of Footscray and surrounding districts to witness the third attempt to induce the alleged flying machine, the invention of Mr Newton Gordon, of East Melbourne, to fly.6

Adding to the writer’s amusement, the motor car used to tow the flying machine in the previous attempts was abandoned for a horse, which was certainly no more successful; ‘a man, armed with a sharp knife, standing by to sever the rope should the apparatus ascend too high. His services were not required’:

Strong men held the wings in position for the start; a rousing cheer went up from the delighted spectators — and with a dull thud the flying machine came heavily to the ground. The inventor and the members of the Footscray Aerial Navigation Syndicate groaned aloud; the crowd roared with laughter, and the horse, unaccustomed to such peculiar proceedings, stopped dead. The animal’s intuition, or presence of mind, saved the machine from utter destruction, and enabled the spectators to get considerably more fun out of the proceedings.5

A second attempt that day was also a failure. Ridiculous as all this might seem, an official observer from the Defence Department was on hand to witness the second trial, a Major Parnell (probably John William Parnell, who was director of engineers at Army Headquarters in Melbourne, though he had recently been promoted to lieutenant-colonel). And the aviation age was just about to dawn. Why shouldn’t Australia be at its forefront? In May, a Sydney newspaper noted Gordon’s failure, but saw value in the attempt:

It would indeed be a feather in the cap of the Commonwealth if an Australian were to forestall M. Santos Dumont in constructing a practicable airship […] Why does not some philanthropist come forward, and offer a substantial cash prize for the first person who succeeds in flying from Sydney to Melbourne? Such an offer would do much to stimulate the talent that is at present lying idle. And when a test service of airships has been inaugurated for the run between the two cities, we may perhaps hope to see the Federal Ministers in New South Wales a little oftener than heretofore.7

But powered, controlled, heavier-than-air flight was not to arrive in Australia for another three years.

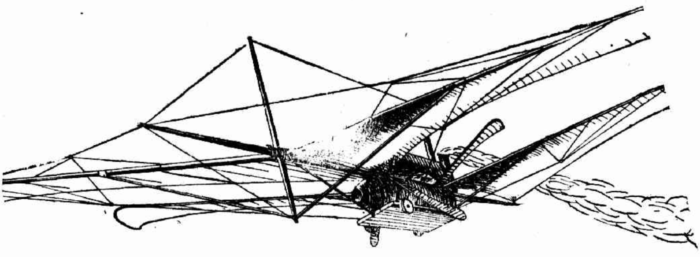

It’s not clear if the Footscray flying machine was another ornithopter. None of the accounts mention the wings flapping, or being intended to flap. One article says that the idea was that ‘the huge wings of the machine would be raised like a kite, and the action of the wind would sustain the airship in mid air’, and Gordon is said to have said (rather unhelpfully) that the machine ‘depend[ed] only on the laws of gravitation for its success’.8 So it was only a glider; and since there was no engine of any kind installed, it could hardly be otherwise.

On the other hand, the accounts emphasise that Gordon always planned to fit an engine in the machine, and since there’d no mention of any propellors and every other single flying machine he worked on was an ornithopter, it seems reasonable to conclude that this was one too. Not only was the 1894 machine an ornithopter, and the 1900 patent an ornithopter, but so was a machine he built in 1909, after moving back to Britain. And so was what seems to have been his last attempt at a flying machine, in 1921 when he was in his early seventies. Enter the ‘Kangartross’:

A real one-man-power flying machine, which has wings like an albatross and legs like a kangaroo, is shortly to make its first attempts to take [to] the air […] No home will be complete without the Kangartross if it realises the faith of its parent.9

It seems that Gordon entered the Kangartross into a Royal Aero Club gliding competition in 1922. 10 And, after that, it looks like his forty or more years of aeronautical experimentation came to an end.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Singleton Argus, 14 May 1907, 3. [↩]

- From Sylvia Black, ‘Dreaming the impossible dream’, East Melbourne Historical Society Newsletter, June 2016, 7; she doesn’t refer to the photograph and it doesn’t appear in any of the sources she cites. [↩]

- Singleton Argus, 14 May 1907, 3. [↩]

- The Age (Melbourne), 3 August 1907, 13. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩]

- The Age, 12 August 1907, 5. The ‘third attempt’ here seems to suggest that this machine is substantially the same as the one trialled in May. [↩]

- The World’s News (Sydney), 15. [↩]

- The Age, 12 August 1907, 5; The Age, 3 August 1907, 13. [↩]

- Straits Times (Singapore), 7 December 1921, 10. [↩]

- Flight, 12 October 1922, 588. [↩]