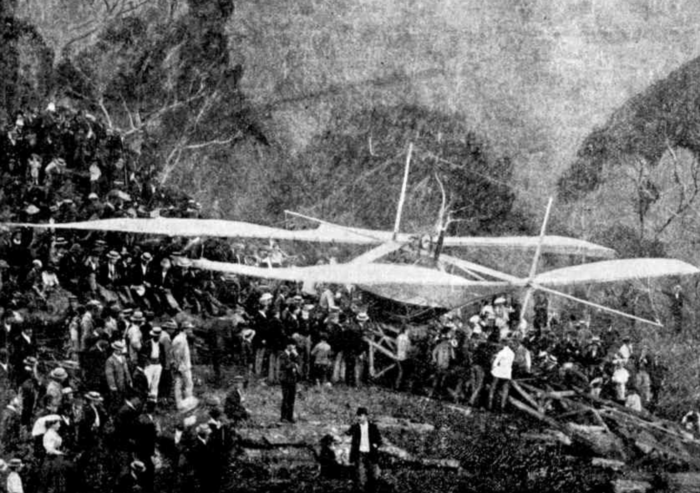

This photograph shows a steam-powered 'flying machine' which was to make the world's first heavier-than-air flight from the cliffs at Chowder Bay, Sydney Harbour, Boxing Day (26 December), 1894. Spoiler: it didn't.

The attempt was widely advertised, even in the other colonies: the Brisbane Week reported that

The management are making all arrangements to propel this little flying machine of 1,100 lbs weight, and 900 square feet wing surface, through the air by steam and ingenious mechanism. Only one person will sample the first flight, but subsequently volunteers will be called for.1

In the end, it was decided to launch the flying machine without anyone in it. That didn't deter the crowds: according to the Bulletin's amused account, 'All the "push" and his "donah" gathered there [...] to the number, it is alleged, of 12,000, and sweltered and drank beer through the long, hot afternoon'.2 The flying machine was set up at the end of a tramway which ran down to the cliffs; the idea was that it would roll down the rails over the edge into the air, and thereby gain lift to soar over the sea into which it, at some point, would fall. But the signs were not promising:

All day the machine stood on its tramway getting up steam and preparing in a dull and hopeless fashion for the promised performance. It was a humble looking thing, cigar-shaped, painted a dull red, and with canvas wings about 50ft across. There was a small boiler in the centre of it, but no visible machinery to connect the alleged steam-power with the pinions, and the whole concern looked about as active as a kedge-anchor.3

This went on for hours, as the crowd got more and more drunk and irritated:

a great crowd surged round and 'poked borak' at the business manager, and the treasurer, and the secretary, and the board of directors [...] The business-manager went round with a worried expression like a man who had much on his mind, and smiled a joyless smile as the crowd urged him to 'let her fly.' As the afternoon went on it somehow became generally understood that if the machine didn’t do something the manager would be badly 'stoushed,' and the excitement grew tremendous.3

Release came at about 4pm, 'when the bay was full of steamers, sailing-boats and skiffs, and the crowd on shore was thickest and most profane':

the Flying Machine stumbled heavily down its tramway and fell over, with a loud noise, on to the beach. There it promptly took fire and the show was over. A chest of drawers or a dead goat would have fallen quite as gracefully, and no more decisively.3

Still, the crowd teetered on the edge of violence:

For a few seconds the assembled push had a vague idea of rolling the management down also, but, thinking better of it, contented itself with rushing down to the beach and cheering the combusted machine, and kicking the ruins of it. Then, after one or two irrelevant free-fights, the show terminated, and the problem of aerial navigation remains unsolved.3

Violence was always a risk in early aerial theatre. A generation earlier and across the Harbour another failed attempt at an aviation first -- the first balloon ascent in Australia -- had led to an actual riot. After the balloon prematurely drifted and then deflated, the would-be aeronaut, Pierre Maigre, had to be spirited away by constables while a crowd of 4000 or more boys and young men destroyed his livelihood:

a cry arose, 'The balloon! the balloon! burn the balloon!' No sooner said than done. The machine was dragged to the spot, the brazier was upset, knocking down a man as it fell, and the balloon was cast upon the fire. A savage yell came from the crowd as the balloon burst into flames, and the spirit of ungovernable mischief seemed at once to be let loose.4

This in turn was just one -- albeit perhaps the most tragic, as a young boy was killed by a falling pole -- of a series of balloon riots stretching from Paris in 1783, in the very first days of flight, to Melbourne in 1858, to Leicester in 1864, to Merthyr in Wales in 1890, and probably beyond. It seems that aviation spectacle could be just too exciting -- perhaps most of all when it didn't go according to expectations.5

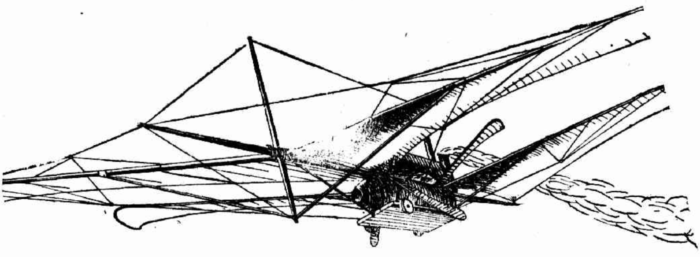

The crowd seems to have more or less behaved itself at Chowder Bay on Boxing Day, 1894. But the failure-to-launch was widely covered in other colonial newspapers, generally with as much or more cynicism as the Bulletin. The South Australian Chronicle, for example, ran a syndicated report under the headline 'THE ALLEGED FLYING-MACHINE. A COMPLETE FIASCO'.6 And, well, the whole affair does seem rather farcical. The carnival atmosphere and the failure to even name the inventor suggests unseriousness. Seaside attractions and fake aircraft went together: at Bondi, the aquarium advertised a 'flying machine' as early as 1889, while in 1907 visitors to Wonderland City could ride in an 'airship' called Airem Scarem.7 The rather spindly contraption in the photo certainly doesn't look very airworthy, and the Bulletin doubted the steam engine was even hooked up to anything. With Hiram Maxim's giant biplane test rig so recently in the news, it all seems like a sideshow gone wrong.

In fact, the Chowder Bay flying machine was a serious, if misconceived, attempt at flight, as I'll show in a following post.

Image source: Town and Country Journal (Sydney), 12 January 1895, 31.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Week (Brisbane), 21 December 1894, 22. [↩]

- Bulletin (Sydney), 5 January 1895, 8. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Sydney Morning Herald, 16 December 1856, 5. [↩]

- See Michael R. Lynn, The Sublime Invention: Ballooning in Europe, 1783–1820 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015); Northamphton Daily Recorder, 16 June 1890, 1. [↩]

- South Australian Chronicle (Adelaide), 29 December 1894, 10. [↩]

- Sydney Morning Herald, 12 October 1889, 3. [↩]

Roger Horky

The passage cited in footnote #6 ends with a reference to "serial navigation." No doubt the phrase was "aerial navigation."

I rely on OCR a lot in my research and am grateful for it (especially when dealing with foreign languages) but it can't be trusted completely.

I've actually reached the point where i can read the gibberish it produces at times. German texts in fraktur are a lot of fun.

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks for that -- yes, an OCR error (not helped by the fact that the original word is actually 'ærial'!)