The earliest cite for the word 'airport' in the Oxford English Dictionary is from 1919:

1919 Aerial Age Weekly 14 Apr. 235/1 There is being established at Atlantic City the first 'air port' ever established, the purposes of which are..to provide a municipal aviation field,..to supply an air port for trans-Atlantic liners, whether of the seaplane, land aeroplane or dirigible balloon type.

As is often the case with the OED's cites, earlier ones can be found (though not many, it is true). The following is from March 1914, from a proposal by the Aerial League of the British Empire to decentralise flying by setting up airfields around Britain:

The time will come when, with the development of aviation, every town of any importance will need an air-port as it now needs a railway station.1

Now, it seems pretty obvious that 'airport' was coined by analogy with the much older word 'seaport', just like 'air power' and 'sea power'. I don't doubt that this is mostly true, but there is another possibility too. The word 'air-port' (with hyphen) did in fact exist before the coming of flight: it referred to a hole for ventilation, especially on a ship or in an engine -- what today might be called an air intake or outlet. I'll come back to this in a moment.

The earliest use of 'airport' or 'air-port' in something like the modern sense that I know of is from a leading article in the Manchester Guardian in March 1913. The Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, had just announced regulations implementing aspects of the Aerial Navigation Acts of 1911 and 1913. The main points of this order were:

- A list of various locations around Britain: flying over these by any non-government aircraft absolutely prohibited.

- Aircraft of foreign governments not to approach the British coast closer than three miles.

- A list of eight sections of coastline: privately-owned aircraft arriving from abroad to enter through one of these sections of the coast, and these alone.

- Aircraft entering the country from abroad through one of these sections to land within five miles of the coast and the person in charge to report to authorities.

It was in relation to the third of these that the Guardian noted

The rules governing the entry of privately-owned aircraft seem to be modelled mainly on maritime regulations, with such special precautions and provisions as the differences in physical conditions require. Chief of these is the creation of eight air-ports, specially prescribed areas along the east and south coasts, at which alone our "territorial air" may be entered by navigators from abroad.2

Note that here, the 'air-ports' (the Guardian's term; it doesn't appear in McKenna's order) are not the places where the arriving aircraft are to land, but the areas of coast over which they are allowed to pass. It seems to me that this has much of the sense of the older meaning of air-port in it: they are like ventilation holes through which foreign aviators could enter Britain's 'territorial air'. Admittedly, it can also be read as an analogy to 'seaport', especially since the regulations are explicitly compared with the maritime model in the previous sentence. I'm happy to split the difference and say both senses were at play here :)

Either way, McKenna's regulations are a reminder of the very different circumstances of international air travel at the time! It makes sense that incoming aircraft were given large areas to land in, instead of specific locations. For one thing, there weren't going to be many airports in the modern sense when flight was so infrequent (after all, it was only four years since Blériot) -- particularly since no runways were actually needed, just a nice flat field or a road. Also, it would have been pointless to direct pilots to land at a specific point: long-distance navigation was a matter of luck at this time, especially over long stretches of open water.3 Such rules were appropriate for the pioneering phase of aviation, but not for the more routine flying of the interwar period.

Another question which interests me is the relationship between, on the one hand, the Navigation Act of 1913 and the Home Office regulations flowing from that, and on the other, the 1913 phantom airship scare which peaked that February. The Navigation Act, which introduced the power to shoot down aircraft flying over prohibited areas, was rushed into law in less than a week (first reading in Parliament, 8 February; Royal Assent, 14 February), and it's tempting to think that it was a direct response to the reports of mysterious and presumably foreign airships flying all over Britain, but in fact the Committee of Imperial Defence discussed an earlier version of the bill in mid-December 1912. The Sheerness Incident the previous October may well have been one motivation -- it was indeed discussed by the CID -- and of course the unseemly haste with which the Act was passed suggests that either the Government felt it needed new powers to deal with the scareships, or at least wanted to reassure the public that it could do so. If that was the plan, it didn't work -- Conservative newspapers were quick to point out that without any air defences, or even an aerial police force, there was no way to actually enforce the new law. But a start had to be made somewhere.

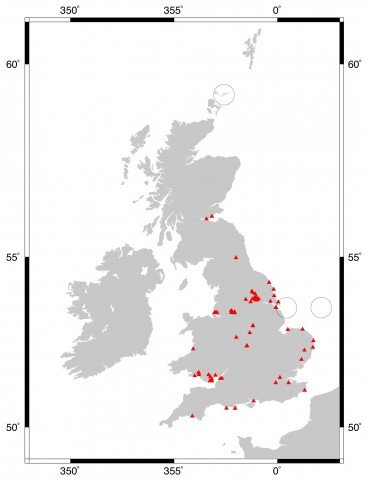

Above is a map from the Manchester Guardian (5 March 1913, p. 8), which I've cleaned up a bit. The named places (ports, forts, wireless stations, and the like) are the no-fly zones; the dark smudges along the coast are the eight air-ports. As can be seen, they were actually quite long sections of coast (except for the one on the north side of the Thames Estuary), which was just as well given the navigational difficulties noted above. Both the air-ports and the prohibited areas are concentrated towards the south-east, which would be by far the most likely places for a foreign aircraft to visit in 1913. Or so one might have thought, if it weren't for the phantom airships! Here's a partial map of where these were seen in 1913:

I'm not claiming that there is a direct correlation between sighting locations and prohibited places, but clearly if you were in the Home Office and worried that the scareships were in fact foreign airships, then you'd want to draw up a wide-ranging list of places you don't want them to go, just in case. Except that in publishing the list you've just handed the enemy air force a great target list ...

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- The Times, 16 March 1914, p. 5. Emphasis added. [↩]

- Manchester Guardian, 5 March 1913, p. 6. Emphasis added. [↩]

- Peter Wohl in The Spectacle of Flight: Aviation and the Western Imagination, 1920-1950 (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2005), 44, makes the point that one of the things about Lindbergh's 1927 flight which was so impressive was that he took off from one airfield (Roosevelt Field, New York) and landed at another (Le Bourget, Paris). Most other trans-oceanic fliers at that time were grateful just to land anywhere in one piece -- if they did manage to, that is. [↩]

Pingback:

Tuesday, 11 February 1913

Pingback:

Wednesday, 5 March 1913