So, as I was saying, there doesn't seem to be much evidence about what was on Tolkien's mind when he was writing The Hobbit, in particular about the issue of aerial warfare. For example, I don't know what he made of the bombing of Guernica, which took place about 5 months before The Hobbit (and I stress again that this might just be because I have not done the requisite research!) However, we might be able to make an educated guess from his feelings as expressed just a few years later, during the Second World War. Of course, the aerial bombardments of that war itself, from Warsaw to Hiroshima and all points in between, would have given Tolkien ample food for thought. But so strong is his hatred of the bomber war in the 1940s that it seems unlikely that it wasn't there in some form in the 1930s.

...continue reading

The dragon will always get through — III

Let's turn now to Tolkien's The Hobbit and Smaug's attack on Lake-town (Esgaroth).1 In my PhD thesis I identified six characteristics of the ideal theory of the knock-out blow from the air: it would be a surprise attack, on a large scale, which would strike at the interdependent structures and civilian morale of its targets, and would wreak massive destruction with great speed. In the 1920s and 1930s, fictional and non-fictional predictions of victory through airpower would usually feature four or five out of these six. As I'll now show, The Hobbit has four: surprise, morale, speed, destruction. Of course, Lake-town isn't a modern, industrial society, nor is Smaug a technologically advanced enemy nation, so the fit isn't going to be perfect. It doesn't need to be, though.

There being so many editions of The Hobbit, it seems a bit pointless to cite page numbers here, but all my quotes come from chapter XIV, 'Fire and Water'.2

...continue reading

- Cf. Janet Brennan Croft, War and the Works of J. R. R. Tolkien (Westport and London: Praeger, 2004), 112-3, for another analysis of military themes in this part of The Hobbit, suggesting that Bard's organisation of the defences is more suggestive of a modern infantry officer than a dark ages hero. [↩]

- The actual copy I'm using is a 1984 edition I read as a boy, a hardcover with beautiful illustrations by Michael Hague. [↩]

Acquisitions

John Garth. Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle Earth. London: HarperCollinsPublishers, 2003. Never let it be said I'm not willing to go the extra mile for this blog! Actually, I read this last year and it's well worth having, not only for Tolkien fans but also as an examination of a different form of postwar literary disenchantment than the usual.

Philip Ziegler. London At War: 1939-1945. London: Pimlico, 2002. A spontaneous purchase because of a single page which will come in handy for an article. But also useful for describing wartime London before and after the Blitz, something I tend to neglect.

The dragon will always get through — II

Let's begin at the beginning:

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

No, that's not the beginning. For understanding J. R. R. Tolkien and the aeroplane, the beginning is the Great War. He may have seen one flying overhead at Birmingham, where he grew up and went to school, or at Oxford, at which he enrolled in 1911. But they were quite rare birds at this time, and Tolkien doesn't seem like the sort of young man who would have been particularly interested in them. He probably would have encountered them when training as an Army officer in 1915, or, at the very latest, when he was posted to frontline service in France in July 1916.

Here Tolkien was thrown into the thick of things, as a signals officer in the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers fighting on the Somme, and aeroplanes were a common sight (there was a dogfight over the village where he was billeted when he arrived at the front). But the only trace of anything aeronautical in his writings at this time are blimps. These seem to have made quite an impression on him. In 1924, he recalled that 'German captive balloons ... hung swollen and menacing on many a horizon'.1 Perhaps he thought they were menacing because they made him think of some weird monster; but they were also menacing in a more direct way, because observers in the balloons recorded British positions and movements, for use in German counterattacks and barrages.

But Tolkien's interest was philological too. After the war he speculated that the world 'blimp' was a portmanteau word deriving from 'blister' and 'lump': 'the vowel i not u was chosen because of its diminutive significance -- typical of war humour'.2 But more significantly, in a lexicon he worked on during the war for his invented Elvish language, Quenya, he added an entry for pusulpë, 'gas-bag, balloon'.3 This was probably added sometime after the Somme and so would seem to be inspired by the 'swollen and menacing' German balloons he had seen: an obvious connection between Tolkien's war experience and his developing legendarium (all the more so because, as far as I'm aware, Elves are not known for their ballooning).

...continue reading

The dragon will always get through — I

Last year Alun Salt pointed out to me a proposal for a collection of essays on the theme of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and history, and asked if I'd thought about sending in something on ideas about airpower and the dragon Smaug. I hadn't, but immediately saw what he was on about! I did a little research, wrote up the proposal below (with a couple of small differences), and sent it in. Of course, it was rejected (or not accepted, same thing).

...continue reading

Acquisitions

Randall Hansen. Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942-1945. New York: NAL Caliber, 2009. Can't do better than to quote the blurb: 'most of the British bombing was carried out against the demands of the Allied military leadership, leading to the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians and prolonging the war. By contrast, American precision bombing almost brought the Germans to their knees. This incisive story of the American and British air campaigns reminds us of the basic idealism and principle that underpin the history of U.S. military power.'

Raphael Samuel. The Lost World of British Communism. London and New York: Verso, 2006. A trilogy of essays Samuel wrote for New Left Review in the mid-80s, recreating the culture and politics of the CPGB in the 1930s and 1940s.

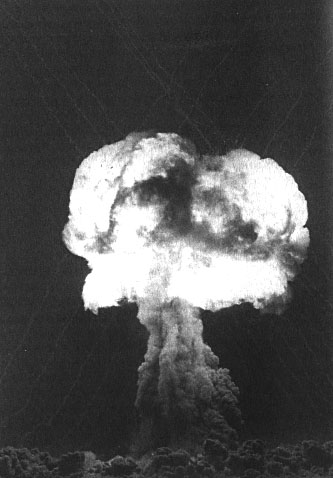

The last time Britain nuked Australia

The last time Britain nuked Australia was at Maralinga on 9 October 1957, over half a century ago. The last of the Antler series of tests, code-named Taranaki (above), involved the detonation of a 25 kiloton fission bomb from a captive balloon at a height of 300 metres. The fallout 'moved east and then north-east towards the Queensland coast, missing the rain areas in New South Wales and Victoria as predicted'. Radiation levels in some areas 'slightly exceeded Level A [no health risk] for "people living in primitive conditions"', more than was predicted but not dangerously so, according to the safety criteria then in place.1 A 1985 Royal Commission however criticised the Antler tests on the grounds that '"inadequate attention was paid to Aboriginal safety", and that the patrols designed to ensure that the range was clear were "neither well planned nor well executed"'.2 Service personnel were also placed in greater than expected danger: a Canberra tasked with flying through the cloud half an hour later to collect air samples rapidly received unexpectedly high doses and had to abort the mission.3

Today the Federal Government introduced a bill into Parliament which will provide compensation and better health care for at least some of the latter group (the local Maralinga Tjarutja people received compensation in 1994). According to Warren Snowden, the Minister for Veteran Affairs:

The bill will benefit Australian personnel who participated in the British nuclear test program and their dependents by enabling compensation and health care to be provided with a minimum of delay [...] The personnel were involved in the maintenance, transporting or decontamination of aircraft used in the British nuclear test program outside the current legislated British nuclear test areas or time periods.

And there may be more to come:

The quality of the records from the test period and the secrecy surrounding the operation means that it is impossible to rule out the likelihood that new information may come to light which warrants further extension of coverage to additional groups of participants.

Not before time, either.

Image source: Nuclear Weapon Archive.

Is there such a thing as folk strategy?

[Cross-posted at Cliopatria.]

Folk physics (or naive physics -- there's also folk biology, folk psychology, and so on) is the term used in philosophy and psychology to describe the way we all intuitively understand the physical world to work. It's very often at odds with scientific physics (unsurprisingly or else there'd be no need for the latter). For example, we all know that in order for something to move, there has to be some force moving it. If you stop pushing a box across the floor, it will stop moving; if a car's engine stops working, the car will slow down and stop too. That's folk physics. Scientific physics disagrees: force causes acceleration, not velocity; in the absence of any other forces, once an object is set in motion it will keep moving forever. Of course it's that caveat which is responsible for the different conclusions of folk physics and scientific physics in this case: friction with the ground exerts a force on the box and the car and so robs them of their momentum. Folk physics works well enough for us in our everyday lives but would be disastrously misleading in, say, trying to dock a spacecraft to a space station.

I wonder if it's useful to apply this demarcation to military strategy? There have been attempts to formalise principles of strategy, of course, though trying to sciencise (yes, I just made that up) them by making them rigid formulae is not necessarily fruitful. Strategy has always been an art much more than a science, and as such is pretty intuitive itself. But certainly there can be (and probably usually is) a gap between what military leaders do and why they do it, and what everyone else, particularly civilians, understand them to be doing. This gap creates a space for folk strategy to exist.

...continue reading

How London was warned

In July, 1917, a new scheme for warning the people of London of impending air raids was adopted. When enemy aircraft were approaching, policemen with a notice warning passers-by to "take cover" went out on bicycles, blowing their whistles to attract attention. When all danger had passed, Boy Scouts went round blowing bugles.

Acquisitions

Alan Brooks. London at War: Relics of the Home Front from the World Wars. Barnsley: Wharncliffe Local History, 2011. What's left? More than you might think -- shelters, bomb damage, memorials (lots of those), even ghost signs. Profusely illustrated.

Zara Steiner. The Triumph of the Dark: European International History 1933-1939. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. With the first volume, The Lights that Failed (which I bought almost exactly six years ago), Steiner has produced the definitive history of the international politics of interwar Europe, at least for a generation or so. Although page 88 could have been improved with a reference to recent work on the British air panic of 1935 :)