The doom of cities

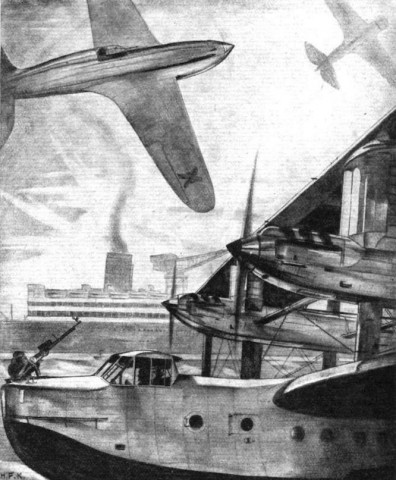

RAIN OF BOMBS Milan’s wonderful cathedral is here shown under a rain of dummy bombs dropped by 80 aeroplanes during recent manoeuvres of the Italians. To make the display more impressive and to ascertain the results with more certainty, luminous “bombs” were used and fell in a fiery rain upon the city — a dire […]