The images in this post are from Boyd Cable, ‘Death from the skies’, in John Hammerton, ed., War in the Air: Aerial Wonders of our Time (London: Amalgamated Press, n.d. [1936]), 20-4 (see below).

The article itself is a short story describing an air raid in the next war. I won’t summarise it in detail, but it argues for the futility of both air defence and civil defence. The RAF’s interceptors never even encounter the enemy bombers (in part because they are stealthy thanks to their silenced engines, only 20% as loud as normal aircraft engines). Though the populace has been drilled well and resists panic, at least at first, they are too vulnerable. A first wave of bombers uses high explosives to block the streets with rubble, making it impossible for fire engines to pass; the second drops incendiaries which set the city ablaze and, crucially, force civilians out of their shelters; and the final wave drops poison gas, which starts killing the now-exposed people on the streets. Now the panic starts and the mob flees, their suffering increased by strafing raiders. The RAF now has its chance, but the city is doomed…

“Proof enough of what we’ve said so long,” growled the one [Air Staff officer]. “Defence as such is a wash-out. Attack is the only useful form of defence.”

“If we can hit them harder and faster and oftener than they can hit us, we win,” said the other. “We can do it, too, if we have more bombers — men and machines — than they have.”

“Yes — if,” said the other wearily. “That’s what we were arguing as far back as the first R.A.F. expansion scheme in — what was it — 1935 and ‘6, wasn’t it?”

THINGS TO COME?

H.G. Wells, in his pre-war fantasy, “The War in the Air,” proved himself an astonishing prophet, a fact that makes these “stills” from his film “Things to Come,” depicting an air raid in the next war, as disturbing to consider as they are terrible to look upon.

REHEARSAL FOR DEATH

Anti-air raid drills on a mass scale have become a feature of German life. This photograph shows an elaborately staged rehearsal of a gas-bomb attack as it might affect civilians, held in the Technical High School at Charlottenburg, near Berlin.

APPREHENSION…

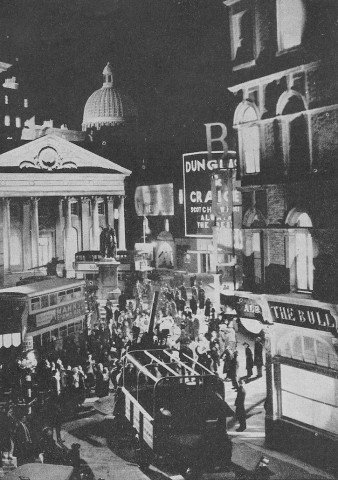

In “Everytown,” a city of the very near future, a crowd watch and strain their ears for the first signs of approaching enemy aircraft; an A.A. gun is ready for action. The photograph is a “still” from H.G. Wells’s film, “Things to Come,” and though, were war to come, the street would be deserted and lights out, it suggests the atmosphere of apprehension.

… AND THEN INFERNO

In vivid and horrible contrast to the scene in the previous page are these two further impressions of a city’s doom, the first representing the street a few moments only after the raid commenced, the second the same street the following day. Though again the limitations of the film studio have perhaps happily prevented the full frightfulness from being shown, there is enough of horror to suggest the fate that may overtake troops and civilians alike in the next war.

Actually, the corresponding scene in Things to Come wasn’t set the next day; or at least there’s no indication it’s not part of the air raid sequence itself.

NIGHTMARE OF THE FUTURE

This reproduction of a German artist’s idea of a scene in London during an air raid in the next war forms in all probability an all too lamentably accurate forecast. It has been suggested in responsible quarters that 100 aeroplanes could stifle a great city with a gas cloud that would rise many yards from the earth, an idea even more terrifying than the though of high-explosive bombs.

War in the Air was a partwork issued weekly, costing 7d. The first issue, in which this article would have appeared, came out on 7 November 1935, a few days before Armistice Day; once complete, all the issues were collected together in a bound volume (which is what I have) around the middle of 1936.

Boyd Cable was the pseudonym of Ernest Andrew Ewart, a Boer War veteran and newspaper correspondent during the First World War. I’m not aware of any specific expertise he might have had in aviation outside of his war experience, though he did write several books with suggestive titles: Air Men o’War (really?), The Flying Courier, Air Activity, The Soul of the Aeroplane: the Rolls-Royce Engine (okay, that one’s particularly suggestive). He wrote a number of other ‘Things of Tomorrow’ stories in like vein for War in the Air, which I’ll discuss in future posts.

The editor, Sir John Hammerton, was the doyen of partworks; Harmsworth’s Universal Encyclopedia sold 12 million copies, and I suspect the wartime The Great War:The Standard History of the All-Europe Conflict and the 1933 A Popular History of the Great War (among other works) were highly influential in shaping the memory of the First World War. (Dan Todman in The Great War: Myth and Memory suggests that these and similar partworks have been neglected by historians, just what I was thinking!) War in the Air also devoted a lot of space to that war, but it was also explicitly framed as a warning about the next war, as the advertisement above, from Daily Express, 7 November 1935, 4, shows:

A Book of Vital Importance to every man, woman and child in the British Empire, called into being by the most urgent problem of our time

WAR IN THE AIR, while brilliantly recording the stirring story of the Past, is mainly concerned with the Future and this, the first publication to deal with the subject in its entirety, gives a vivid picture of the dread menace of aerial warfare […]

THIS is no mere book of thrills and startling pictures, it is a living, vital thing that ought to enter into your life and help you the better to bear your part in the most urgent need of our time — the need to make Britain as powerful in the Air as in times gone by she was dominant at sea.

Amidst the scaremongering there’s a very hard sell going on here, and not a little hyperbole too (‘the most important and significant publication issued in this country for a generation’!) But mixing profit and patriotism never did any harm.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Step 1: Patriotism

Step 2: Panic

Step 3: ?

Step 4: Profit!

Except we’ve figured out step 3, which makes us even smarter than underpant gnomes.

Notice how one myth of war is preserved in these images? The bodies are whole.

Erik:

Well, do tell! What is step 3? Presumably it begins with P.

Mark:

Good point! Yes, images of mutilated or dismembered bodies are exceedingly rare in the imagery of bombing from this period. They were perhaps most likely in pacifist and other radical literature designed to shock people into awareness of the threat of war. But I wonder if it is more about sensibility than mythology? It was certainly permissible (though I still wouldn’t say common) to describe such things in words. After the Western Front (and more especially the wounded returned soldiers) there must have been a greater awareness of the effects of shrapnel and high explosive on the human body. But that doesn’t mean people wanted to look at the results. Today we’re far less sensitive to images of shattered bodies; but even so I still find the few images of (real) dead bodies in my sources disturbing and it’s my general policy not to reproduce them on this blog. (I think I’ve only done so once, and that also is, as far as we can see, a whole body.) Though I suppose it is precisely by such silences and reluctances that myths are passed on to the next generation.

With these particular images, isn’t the lack of severed limbs better explained by the fact that most of them are stills from _Things to Come_, in which severed limbs would have been too expensive to fake for just one scene, and the other is a drawing illustrating the special horrors of gas attack, rather than high explosive?

Fair point about gas (though if they wanted to be gruesome they still could have). But I disagree about Things To Come. It may only be one scene but it’s the pay-off to the air raid set-piece which dominates the first act of the film. Having spent so much on the sets and special effects, why skimp at that point if you’re trying to impress upon your audience the horrors of aerial bombardment? Severed limbs, pulped faces, intestines strewn over the road — that would do the trick. It seems more likely to me that such things were more or less unrepresentable in 1930s British cinema. But I’m happy to consider counter-examples!

Does the Lewis Milestone version of All Quiet on the Western Front count?

43 and a half minutes into the DVD copy I bought a couple of years ago, during the first big setpiece battle, a French soldier reaches out to a strand of barbed wire and is obscured by smoke and debris from two explosions. When the smoke and dust clears, two hands, one severed at the wrist, the other with a bit of sleeve attached. They only appear for a few frames, and the film cuts to Lew Ayres averting his eyes in disgust.

I was quite surprised to see this because I’ve never noticed it when watching the film before. Apparently I first saw All Quiet.. when I was 9 or 10 because I wrote a poem which was published in the school magazine despite being about thirty verses too long* (my parents kept a copy…), and I’ve seen it several times since, all without severed hands.

This edition claims to have been restored by the Library of Congress Motion Picture Conservation Center, so I’m wondering whether there’s always been a difference between the US released and UK released versions, or if some new footage had been found.

* They were short verses.

Pingback: Airminded · The doom of cities

Yes, that very definitely counts! It was an American film, but it had to pass the British film censors so that’s just as good a guide to what was permissible in British cinema as a British film. I found an article about how the different versions and how it fared with the censors: Andrew Kelly, ‘All Quiet on the Western Front: “brutal cutting, stupid censors and bigotedpoliticos” (1930-1984)’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 9 (1989), 135-50. Kelly notes the severed hands scene, and explicitly notes that it was included in the 1934 and 1939 re-releases (and presumably in the 1930 first release). However, he doesn’t actually say whether that scene was seen British cinemas (as opposed to simply being in the cuts re-released in those years). I think it probably was, but it seems that the BBFC records are not as complete as might be desired. So I have to backpedal from my dogmatism a bit. You could show severed limbs, at least if you didn’t dwell on it (the scene in All Quiet is only a few frames). But I still doubt that mass carnage that such a scene would entail in Things to Come would have been attempted. (On Mark’s original point, the air raid scene actually ends on a shot of the body of a small boy introduced earlier in the film: he’s buried under rubble but has no visible no wounds or even a mark on him, if I recall correctly).

Incidentally Kelly also explains why you wouldn’t have seen the severed hands before, Rik: the cut of All Quiet purchased by the BBC in the 1960s is the one usually seen on British TV, and while it restored some previously cut footage, it deleted the severed hands (Kelly speculates) because it was intended for a TV audience.

Pingback: Airminded · New horrors of air attack

Another ‘severed hands’ reference, because I came across it recently. From a passage in Jonathan Rose, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001), 359, on the impact Hollywood films made on British audiences, quoting the autobiography of ‘An Irish laborer’s son in Clapton’ published in 1958:

Pingback: Airminded · If war should come

Pingback: Airminded · When war does come

Pingback: Airminded · Future schemes of air defence