In June 1936, Flight published a short story entitled 'If, 193--? A conjectural story'. It's interesting as an example of an air force view of the next war. That is, for the RAF it goes pretty much according to plan: the enemy's attempt at a knock-out blow against Britain fails, whereas the RAF plays a key part in Britain's victory. The author and illustrator, H. F. King, was only 21 or so when this story was published; in July 1940 he became a pilot officer in the RAF, and after 1945 wrote a number of books about aeroplanes (including a couple of entries in the authoritative Putnam series). I don't know what his relationship to the RAF was at this point, but he seems to have been pretty well-informed. Or perhaps he just read his Flight cover to cover every week.

The situation is as follows:

Through indefensible aggression Eurland had secured a number of Continental bases, the nearest being not more 400 miles distant from the English coast. It was apparent that the enemy intended to push his way toward the coast and to acquire additional aerodromes from which to operate all manner of aircraft, including his short-range fighters.1

One of the few characters in the story, a planespotting young ship's engineer (perhaps modelled on the author himself) muses that it was 'Funny to be thinking about war with Eurland, of all countries. Still, there was no accounting for the machinations of the politicians'.2 The reader should NOT identify this 'Eurland' with any real Germany, as an editorial comment makes clear. Did I say 'Germany'? Sorry, I meant 'country'.

THIS story is not intended as a forecast. Indeed, any mention of politics, foreign countries or exact period have purposely been omitted. Rather it is intended to tell something of what might be expected should Great Britain be attacked from the air after her Royal Air Force has been made stronger than it is to-day.2

This last sentence gives the game away: the story is an argument for the continuation of RAF rearmament (i.e. the one triggered by German rearmament), which had begun only a year or so earlier. King has a paragraph on how expansion has fared by the fateful year of 193-:

Some of the fighter units were still flying the Gauntlet. More were using the four-gun Gladiator and the improved Fury. The Hawker monoplane was just beginning to percolate into the Service and threatened to turn all fighter tactics topsy-turvy. We had scores of Blenheims, Battles, and Wellesleys, in addition to the obsolescent Hinds and Ansons. Our heavy bombers included the Heyford and Hendon (both due for replacement), the Whitley, and various types of more modern design.2

'None of these' latter, King remarks, 'bore any trace of the slackening in the pace of bomber development during 1933, when the British Government recommended restrictions on the all-up weight of bombing aircraft', presumably referring to Britain's proposals at the World Disarmament Conference.2

While Eurland's ground forces are advancing towards the coast, its bombers 'do their utmost to terrorise London'.2 Without air bases closer to Britain than 400 miles away, they must attack without fighter escort. Ten squadrons of twin- and four-engined bombers take off at midday and arrive over the Channel about 2pm. There they are met by the RAF:

the Gladiators and Furies had torn into the enemy formations on their way to London. Of the machines which had reached the Metropolis the majority had released their bombs south of the river. Whether by accident or judgement, a complete salvo fell in Kingston not many hundred yards from the Hawker factory. Three hundred dead were reported from the suburbs, and a quarter that number from the city. A number of large fires were started [...]3

'London trembled at the thought of the night', but has protection in the form of 'night fighters, anti-aircraft guns and searchlights, the sound locators, and the Observer Corps'.2 Trawlers and destroyers reported the passage of enemy aircraft overhead, as did the yeomen of England:

Somewhere in Kent a little band of villagers -- one of many -- sworn in as Special Constables, took up their vantage points to wait for the raiders they knew must come and to report their height and direction. There was the parson, farmers and the baker, each inwardly thrilled that he was taking part in defending this, his country. As the schoolboys on the village green shouldered their bats and stumps and chattered off into the dusk, a car hummed up the hill and pulled into the roadside, and the constable started forward to open the door for the rubicund squire, who eased himself out on to the grass and snapped at his spaniel to camouflage his excitement.

Such scenes were common all over south-eastern England [...]4

The information supplied by all these sources suggests that five waves of Eurland bombers were coming up the Thames for London. Eighty fighters (Gauntlets, Gladiators and Demons) are sent up to patrol Essex and Kent at 12,000 ft. One type in particular has some success:

The Gladiators represented the last of the dog-fighters -- highly manœuvrable biplanes in a class developed by Great Britain to a higher pitch than by any other power. Their spectacular tactics, however -- utilising incredible dives, zooms and turns were soon to be rendered obsolete with the advent of the 300 m.p.h. fighters, which showed that aerial tumbling could be performed only at comparatively low speeds. Anyone attempting to defy the laws of nature was whisked into temporary oblivion by "g" -- a force of unbounded power unleashed by the slightest movements of the hands.2

But many bombers get through to London:

A large percentage of the projectiles contained gas, for which London was barely ready, but it was chiefly the high-explosive bombs which made that night so devilish that even the destroyers were stunned by the horror of their handiwork.2

Even so, 'It would take many a night's bombing to reduce London to the heaps of ruins talked about so glibly in the pre-war Press'.2

And what of Britain's own bombers? The heavies are held back until the enemy munition stores are located, but as soon as the first Eurland raid is detected, the RAF launches immediate 'reprisals' -- not against the enemy's cities but its airfields, so that 'in the event of their return, the enemy squadrons should be unable to recognise their aerodromes'.5 This is a job for the Blenheims whose 'superlative speed and medium-weight bomb load place them in a class which was much to be desired'.6 The eight Blenheim squadrons actually pass the first enemy raiders over the Channel, but neither side 'dared deviate one degree from its set course, for an engagement would have ruined any chance of success in its primary mission'.2 They continue at high speed towards the Eurland frontier, there meeting enemy fighters:

They would have to be good to break the Bristol formation. What luck. Fanhar 34s. No more than 250 flat out -- if that. But plenty to cope with. There must have been fifty of them. And he was the bull's-eye. Funny. Here he was leading a British force in the first aerial battle since 1918, and all his duty required of him was to open the throttle a bit wider.

Then a pneumatic drill got to work on his windscreen and instrument board. It danced around gaily, shattering the glass and clipping fragments from the casings. A boost gauge gone; a rev. counter....2

Eight of the Blenheims are shot down and about the same number of Fanhars, meaning that the defenders had about twice the loss rate as the attackers. The Blenheims do their job, as one of the aircrew reflects: 'the personnel of certain squadrons, in the somewhat questionable event of their return, would go without their tea'.2

After the first day, the air war repeated the same patterns but with less intensity. Eurland's 'Bombers tried for dockyards, factories, aerodromes' but find it difficult to penetrate inland.

They learned respect for the "Archies" and searchlights in the darkness of the suburbs; for the Furies which seemed to leap at them from the ground; for the incredibly fast Hawker monoplanes which showed themselves more frequently and chased them back to the coast.7

For their part, the RAF's bombers had to concentrate on the ground war: 'although they managed to delay the advance of the Eurland forces toward the coast, they failed to stem it entirely'.2 After two months of war, Eurland arrives at the coast, taking 'four bases just across the Channel from which the fastest of her fighters could be over English soil in fifteen minutes'.2 The RAF harasses the airfield construction (using Hinds) and makes 'a great concerted effort to wipe out some of the main munition factories'.2 But it also becomes aware of rumours that Eurland

planned to follow up a period of intensive bombardment on the coastal districts of England by landing troops from a fleet of warships and commandeered liners said to be assembling at a port about 400 miles. Although there was little case to fear him on the sea, it was deemed advisable to send a reasonably strong force to reconnoitre the harbour and at the same time to inflict all possible damage on the shipping.2

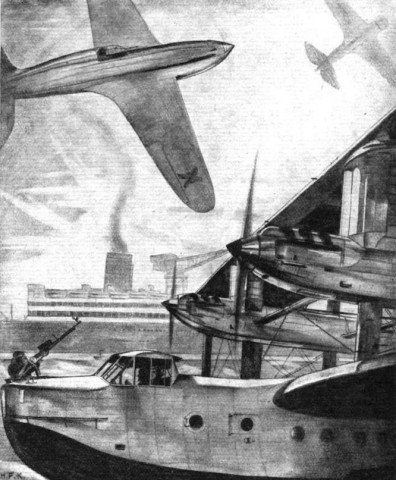

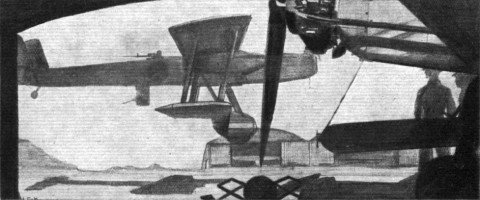

This operation is carried out by Singapore flying boats and Heyford bombers at dawn (see the illustrations above):

Out of the early morning mists swept the green and silver armada and, by good fortune, caught the entire harbour unprepared. As the Heyfords arranged themselves for their attack they seemed to give the observers in the Singapores just time to note the appearance of the target in its entirety. Then salvos crashed into quays, warehouses and through the thin, unarmoured decks of merchant ships ranged alongside. If ever a plan existed to use that fleet for the invasion of England an extensive revision of the programme was necessary.8

The enemy fighters find it difficult to engage the Singapores skimming low over the water's surface, as they are unable to attack from below. The British bombers return home without loss.

The RAF now has the upper hand over Eurland's air force; apparently its counterforce strategy has paid off. Indeed, the war is soon over:

The turning point of the war was a week's merciless bombardment in all weathers by British machines on the big Eurland centres. Day and night, bombers of every type flew out over the Channel, to return, perhaps, after a few hours to rearm and fly off again. On one occasion a squadron of Wellesleys penetrated so far inland that it found the depot which it was to bomb almost completely lacking in defence against air attack.

One evening a squadron of Battles returning from a raid reported much less opposition than was usual. That same night, when well on its way to the target, a squadron of Whitleys was recalled by wireless. And that signified only one thing.2

'If, 193-?' is interesting as prediction. Based on the aircraft is use one might pick 1938 as the 'actual' year. But in some ways it's 1940, when Germany advanced to the Channel coast in a few weeks, took aerodromes within fighter range of southern England and began to prepare an invasion force. In most ways, of course, it's not (and one could just as easily say it's 1934, when the Army got money for a Field Force to secure the Low Countries against their occupation and use as a launch site for a knock-out blow, or 1909, when bolts from the blue were all the rage). It seems odd now to read that fast monoplane fighters (the not-yet-Hurricane and the largely unknown Spitfire) would make dogfights a thing of the past; but biplanes are more manoeuvrable in general, and without much experience to go on it wasn't an absurd idea. The special constables/Observer Corps thing, with its popular basis, seems a bit like an airminded Home Guard; though the idealised vision of village life is hardly Tom Wintringham.

As I said, King's scenario pretty much is as the RAF would have written it; some of the episodes even sound like they were inspired by certain of the Hendon set pieces, and it seems a bit unsporting that the British bombers fare are able to press home their attacks in the teeth of air defences when the enemy bombers are not. I'm not sure how closely the idea that counter-bombing aerodromes and aircraft factories in retaliation for a knock-out blow corresponded to actual RAF doctrine; but it was widely described to the public as such in the 1930s. It certainly avoided thorny questions about the morality of bombing cities; and King is noticeably coy on this point when it comes to describing the effects on civilians of British bombing of Eurland's 'centres'. 'If, 193-?' is a relatively rare attempt to imagine the next war in a way that didn't scare the hell out of its readers. But remember that proviso: if. If the RAF continues to expand. P. R. C. Groves and other pro-rearmament writers who did try to scare the hell out of their readers did so by envisaging a world where the RAF was not big enough. King was really just showing the other side of the same coin.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.