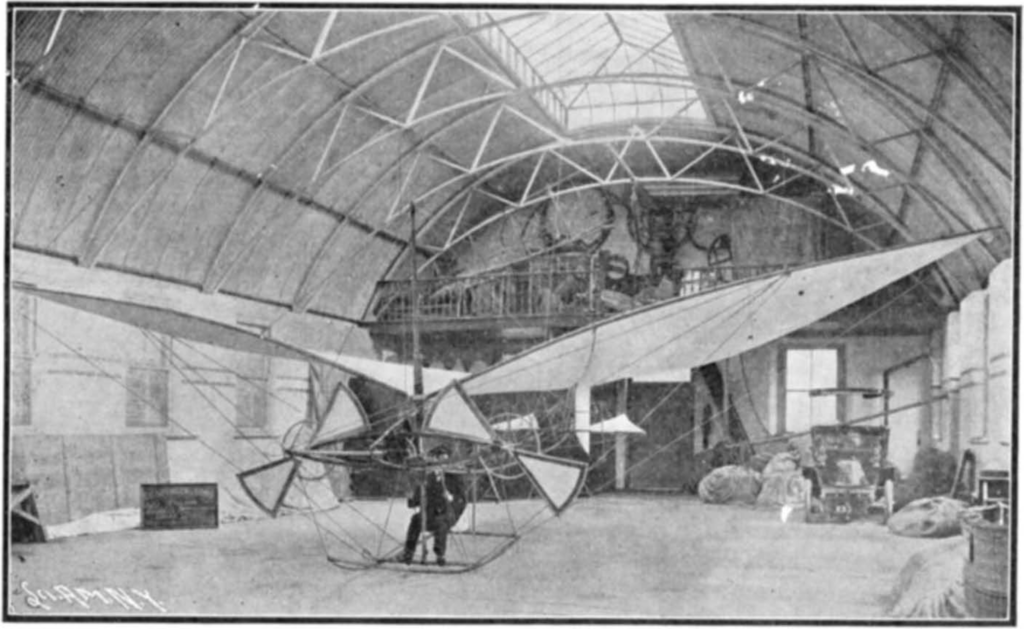

The mysterious flying machine of the mysterious Señor Alvares — III

So how can we find out the identity of the mysterious Señor Alvares? The press is no help; I’ve checked British Newspaper Archive, Gale NewsVault, Chronicling America, Gallica, and Trove. The aeronautical press is no better, since 1904 is before Flight or Aeroplane. All I can find is that he was a Brazilian called Alvares, […]