Here is what I’ve been able to reconstruct about the Alvares flying machine. Firstly, nothing about Alvares himself, except that he was a Brazilian, who was said to have successfully carried out experiments with smaller gliders in his home country for some 18 years.((Manchester Evening News, 17 September 1904, 3; Daily Mirror (London), 17 September 1904, 11.)) Frustratingly, no other names are given — he is always Senor (or Señor) Alvares.

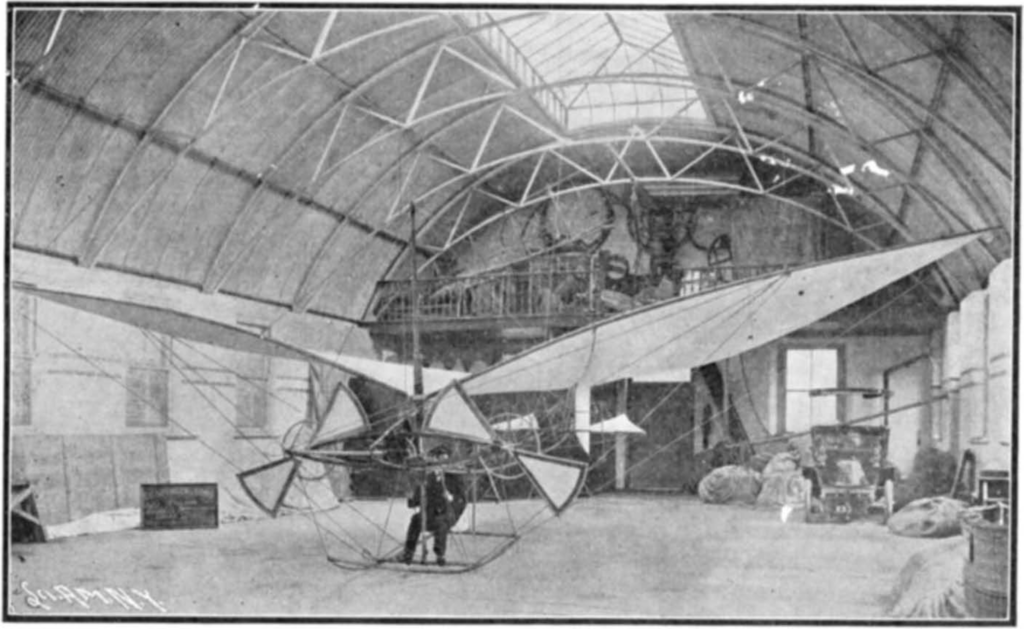

Above is the one (1) photograph of the aeroplane I’ve been able to find (thanks, Scientific American!)((Scientific American, 17 June 1905, 480.)) It was built by C. G. Spencer and Sons, a well-known manufacturer of balloons and even small airships, between about May and September 1904, in their ‘Balloon Hall’ at Highbury Grove, where it was exhibited on 16 September, ‘a pretty bird-like structure, weighing about 150 pounds […] capable of holding only one man’.((Standard (London), 17 September 1904, 2.)) Indeed it was said to have been inspired by the flight of gulls and their ability to soar in the air for long periods. Alvares was present for the initial demonstration along with ‘several members of aeronautical societies’.((Manchester Evening News, 17 September 1904, 3.)) The intention always seems to have been to fly it initially without any pilot (though ballasted at 150 pounds), but to release it from a balloon so as ‘to test its actual power of flight’, with ‘a perfect balance’ being the goal.((Standard (London), 17 September 1904, 2.)) However, the first reports say this was to be done at the Crystal Palace in the following week; it’s not clear why it took place at Hendon a month later instead.

The Standard gives a good description:

The machine consists of two wing-like aeroplanes, measuring 40ft from tip to tip, attached to outstretching arms, and fixed to a bamboo framework. Beneath this framework is a seat for the aeronaut, who can control the mechanism, which comprises a Minerva motor of two horse-power actuating two propellers, each five feet in diameter, and supported on outriggers situated in front. At the rear of the framework are two rudders controlling the upward or downward motion, and a larger rudder for guiding the machine to the right and left. The motor was worked yesterday and seemed to go very easily, making about 240 revolutions a minute. The rudders, too, were under perfect control.((Standard (London), 17 September 1904, 2.))

As for the actual flight on 14 October 1904, none of the British press accounts give much more detail than the Australian report I found first. So here’s Scientific American‘s (belated) description:

The aeroplane was attached to the balloon and when an altitude of 3,000 feet was attained the motor was set in motion and the airship was cast adrift, its progress being followed both from the occupants in the car of the balloon, and a group of interested experts on the ground below.

When the aeroplane was liberated it plunged rather erratically toward the earth for some distance. When it had regained its equilibrium, however, it sailed steadily in a horizontal direction. The propellers revolved rapidly and the aeroplane maintained its balance in a perfect manner. It traveled at a high speed for over a mile, and then came slowly and steadily to the ground as the power of the motor became exhausted. The experiment was attended with complete success, and testified to the efficiency of the design.((Scientific American, 17 June 1905, 480.))

This confirms that the engine was running, making it a powered heavier-than-air flight. Since it was also unpiloted (!) I’m not sure if we can call it controlled. In any case it doesn’t seem likely that the tiny 2hp engine contributed much, if anything (the Wright Flyer’s engine was 12 hp), nor was there any intention to even glide. According, again, to Scientific American,

The machine is not supposed to drop vertically or to glide in the same manner as the flying machines of Lilienthal and Pilcher, but to descend gradually in a series of aerial jumps, as it were. Gravity is the power-giving motion, the motor simply exercising an accelerating or retarding influence so that the curves will be of a great radius.((Ibid.))

Taking the numbers at face value (a 1 mile glide from an initial height of 3000 feet) the glide ratio comes to 1.76, which is not great (it’s somewhere in the vicinity of the Space Shuttle, the so-called ‘flying brick’). Not quite gull-like, but better than free fall, I suppose. But it really just sounds like a glider with a little motor attached (Minerva made literal clip-on engines, to convert bicycles into motorcycles). At least stable flight was achieved, Alvares’s stated goal.

Unfortunately, despite the apparent soft landing and the plans for ‘A larger machine with a motor having sufficient power to lift the machine from the ground’, I can find no evidence of further flights by Alvares’s flying machine.1 But at least it’s somewhat less mysterious now, though the same can’t be said for Alvares. In a final post, I’ll try to dig a little more into who he might have been.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Ibid. [↩]