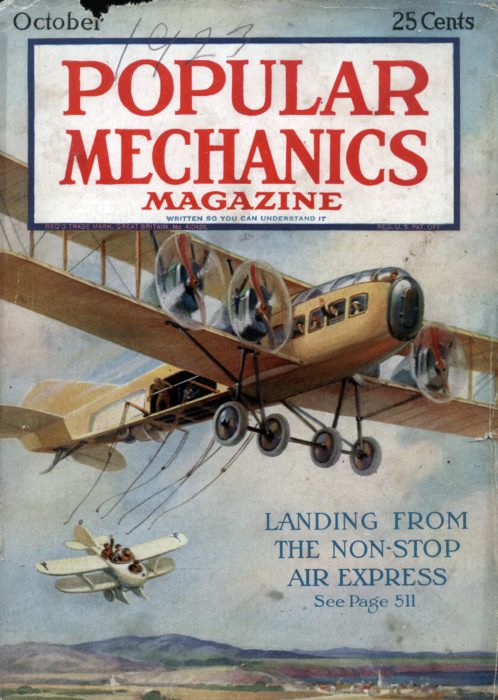

John Ptak asks of this cover from the October 1922 issue Popular Mechanics: 'why?' It's a good question. The accompanying article doesn't really help:

Consider yourself aboard a giant airplane whose whirring propellers rapidly drive from view faint objects on the earth far below. As towns and hamlets recede in the distance you realize that you are fast approaching the one that is your destination, for the captain is giving orders to make ready for the discharge of passengers at one of the intermediate points along the route of the great air liner. The crew unfold from the capacious hold a small air boat, and lower it dangling from the huge hull by its special tackle. You and several fellow passengers climb down into the seats behind the pilot and buckle yourselves in as the big ship slows its engines to enable the little wings to catch the air. With a quick movement of a lever your steersman unleashes the small craft, which begins its motorless flight and gracefully glides downward to a safe landing, while the mother plane speeds out of sight.

It turns out that this was an idea which cropped up repeatedly in the first few decades of flight. But such 'aerial trains' never quite came to commercial fruition. Which suggests that yes, you could indeed consider yourself leaving an airliner in mid-air; but you probably wouldn't want to.

Setting aside such oddities as airships on rails, or trains with wings, more usually aerial trains were conceived of as a powered aeroplane towing one or more gliders, as in the above 1931 illustration, or in this 1922 scenario:

An ordinary aeroplane with certain adjustments and modifications, is linked up to a number of motorless gliders, similar to those which have been successfully flown in Germany of late. It pulls these through the air exactly as an engine pulls the carriages along the rails. Imagine such a train flying from Sydney to Melbourne, carrying passengers for Goulburn and Albury as well. All the Melbourne passengers would be accommodated in the aeroplane proper. Those for Goulburn would be seated in the rear carriage, and those for Albury in the carriage next the engine. When the aeroplane arrived over Goulburn it would descend to about 3000 feet. The rear carriages would be detached and would commence to glide to earth under the control of its pilot, landing on the aerodrome provided. The 'engine' and the Albury carriage would continue their flight until Albury was reached, when the process would be repeated, leaving the aeroplane proper to continue its voyage of discovery to Melbourne.

My first thought was that this was an aerial version of a railway slip carriage, which is a passenger carriage that is uncoupled from a train while it is still in motion, something that was actually done in Britain between 1858 and 1960. The carriage would brake to a stop at the next station, while the train itself would keep going. The point of this was to save time on express or busy routes -- not just the time that would have been lost waiting at the station, but the time that would have been lost in slowing down to a stop and then speeding up again. Time is a critical factor in airline operation too, so a slip glider like this could make sense, and indeed the Popular Mechanics cover above teases its aerial train article 'LANDING FROM THE NON-STOP AIR EXPRESS'.

The term 'slip' was sometimes used in connection with with these kinds of experiments. In 1934, Gordon England, a pioneer glider pilot, suggested the idea of

an aerial train, say, from Egypt [...] flying at 20,000 feet, with slip coaches for places like Rome, Paris, Berlin, and so on. They could get down from such a height without the use of any power. Imagine running a service of goods machines along the backbone of England, with slip vans from either side.

In 1936, one newspaper described a new Soviet 'Flying Train' service from Moscow to Vladivostok as 'Slip Coaches of the Air'. In this case 'many' (but unnamed) 'aeronautical experts' were said to be 'of the opinion that the flying train is to play a tremendous part in the future of passenger transport':

They visualise the time when machines will set off on long journeys towing behind them from four to six or even more gliders which will be 'slipped' at the various cities along the route, each being in charge of a pilot, or, to look even further into the future, there is the possibility of the gliders being controlled to their destination by wireless.

I can't find any confirmation that this aerial train service was actually real; if it did it seems to have received no other press coverage. (Given the difficulty of getting reliable information out of the Soviet Union at this time, I suspect the journalist got his information wrong.) But the Soviets did have an interest in aerial trains. In May 1934, a 'so-called aerial train, consisting of an aeroplane and two gliders, completed a successful flight to Moscow from Saratov, a distance of 520 miles, in a little over 10 flying hours' (not exactly fast). Two months later the Soviets set 'the first distance record for aerial trains' of 800 miles:

Several landings were made, the glider pilots detaching and coming down singly. The take-off, with the three gliders strung behind, is simple. The average speed between towns is 110 miles an hour. Moscow authorities are jubilant. They see the momentous spectacle of sky freight trains as practically at hand.

It wasn't just the Soviets, either: at various times in the 1920s and 1930s, American, British, French and German aviators experimented with the idea of aerial trains. In May 1943, a 'glider train' of one aeroplane and two gliders, each carrying 443 lbs of goods, flew from Chicago to Denver; then, in July, a RAF Dakota towed a glider filled with 1.5 tons of supplies for the Soviets 3500 miles across the Atlantic: 'The shape of things to come', said one newspaper.

But as we know, things didn't shape out that way. Why not? I suspect that aerial trains simply became unnecessary. When airliners were slow in speed, few in number and low in payload, it made some sense to get the most value out of them by towing extra cargo and passengers behind, especially on routes in competition with rail and (increasingly) road transport. But the Second World War created a surplus of capable transport aircraft, even before the jet revolution of the 1960s. Besides which, aerial trains would have been a cumbersome solution and only ever a partial one: it's one thing to drop passengers off in a glider, but they can't come up that way. The hub and spoke model is better at getting people where they need to go. In any case, there seems to have been little interest in aerial trains after 1945; one of the last I can find was in Australia in 1951, when three pilots from the Hinkler Soaring Club planned 'the longest glider tow ever attempted in the British Empire', some 550 miles, from Bankstown to Toowoomba.

Of course, there is one use of aerial trains which I have conspicuously avoided mentioning: the military one. Gliders were famously used in airborne assaults on a number of occasions in the Second World War, though as far as I know they were only towed singly, which isn't much of a train. In 1940, however, the Tushino air display -- held 'in the presence of Soviet political and military leaders, diplomatic corps and 500,000 spectators' -- included 'an airtrain, consisting of 27 gliders, which discharged a swarm of parachute troops'. And as early as 1908, Count Zeppelin was reported to have taken 'a patent for an aerial train of four airships, each to carry 250 soldiers', This could be the basis for Rudolf Martin's absurd claim, made just weeks later, that within two years Germany would possess enough Zeppelins to carry 350,000 soldiers across the English Channel in the space of half an hour. That led to Britain's first air panic, and is why my book starts in 1908. So, in a way, this is where I came in.

Image sources: Popular Mechanics, October 1922, via Modern Mechanix; Sydney Mail, 13 May 1931, via Trove.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Marc

Actually, short range glider operations often involved towing two assault gliders with one tow aircraft. I've seen pictures of US, UK, and German assault gliders in dual tow:

https://www.britannica.com/technology/glider-aircraft/images-videos/media/235331/5694

http://www.atterburybakalarairmuseum.org/wwii-glider-pilots1.html

The drag of two gliders consumed too much fuel for longer range missions, which is why few such pictures exist. I'm a sailplane pilot, and at one airport we routinely flew dual glider tows to a 30 mile distant mountain ridge up until a decade ago. A near fatal accident (the issues are obvious) put a stop to that.

Of course, the truly amusing stuff in this realm was the USAF FICON projects of the 50s, such things as attaching fighters to bomber wingtips, underneath the fuselage, even a compact fighter to fit inside a bomb bay, all flight tested.

JDK

Another use of the term 'slip' in this context is the slip wing Hurricane, which resulted in the Hilson Bi-Mono. Those lead to the idea of jettisonable fuel-carrying wings, to increase range which seem bizarre, until you realise drop tanks seems exactly as bizarre until they became the 'obvious solution'. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hillson_Bi-mono

Roger Horky

I must express surprise that this phenomenon was compared to a railroad experience rather than a boating experience... My first instinct was that ships can/must anchor away from shore on occasion and so must take boats to get to land, and these these "air slips" were more akin to lighters and jolly boats. I had no idea that some trains did not stop but simply release a car or waggon in its wake.

Roger Horky

Is this where "slipstream" originates?

Brett Holman

Post authorMarc:

Ah, thanks -- I knew that if I made such a confident assertion off the cuff that it would come back to haunt me! And your point about the excessive fuel consumption would surely help explain why slip gilders weren't used for civilian transport either.

JDK:

Thanks, I hadn't thought of the old slip wing as being related linguistically, but certainly there are similarities. Maybe slip glider was the inspiration for the term slip wing? The first time the term is used in Flight is in 1940, by none other than Noel Pemberton-Billing. He claimed to invented the concept in 1912, but perhaps the term came later...

Roger:

Apparently it was a pretty rare practice, mostly (entirely?) confined to British and Irish railways.

I think slipstream is a different coinage, from aerodynamics? Here's Flight in 1910:

and

Here slip seems to be in the sense of a slippage between two states, rather than, in the case of the slip glider (and the slip wing), one thing slipping away from another. But I'm sure another case can be made!