So we've seen American claims of a British secret air defence weapon in the Battle of Britain; American claims of British secret air defence weapons in the mid-1930s; and American ideas for superweapons to break the deadlock of the First World War. What do I mean suggest by these examples? Why have I called these posts 'The superweapon and the Anglo-American imagination'?

Actually, the phrase 'Anglo-American imagination' is misleading, because I think the British and the American imaginations were significantly different, at least when it comes to technology and war. And the difference is this: at least in the period of the two world wars, Americans found it much easier to imagine that technology could help them win wars than the British, who were more pessimistic and tended to see new technologies as a threat. It's easy to get into trouble with big generalisations like this, and I definitely can't quantify it in any useful way. But I don't think it's accidental that it American journalists imagined British superweapons more readily than British journalists, or that American science magazines had superweapons on their covers, and British ones didn't.

My argument on the American side is mainly from secondary sources. The inspiration for the title is a book by H. Bruce Franklin which has the subtitle 'The Superweapon and the American Imagination'.1 Franklin covers a broad swathe of cultural and polical history from Fulton's submarine through to SDI and shows how embedded the idea of better security through higher technology is in American culture. Complementing this is Joseph Corn's The Winged Gospel.2 Here the argument is that Americans generally believed that aircraft -- and the new connections they would create between people and peoples -- would bring about a golden age of peace and prosperity. The same could not be said of the British (at least, not in general).

Having hesitantly asserted a bold generalisation, I probably ought to try and explain it. Here are some possibilities, none of them particularly compelling:

- Time. The First World War was much more traumatic for Britain than for US. Technology didn't make things better. Artillery, gas, machine guns, barbed wire, brought stalemate on the Western front, not victory. Britain's lead in dreadnoughts didn't help much against U-boats. And so on. But America entered the war as a fresh force; and its army had only recently become seriously engaged in combat by the time of the Armistice. So even though it had its own learning curve to follow, it had no time to become embittered with the apparent fruitlessness of military technology.

- Space. Britain is both geographically smaller than the United States, and closer to its neighbours (in terms of the distance between population centres, at least). It had less need for faster transportation internally, and as for for bringing Europe closer, this has not always been a universally cherished ideal in Britain (cf. Channel Tunnel, European Union, Napoleon, Wilhelm II, Hitler). America is far bigger and more dispersed; it's easy to see why it would embrace aviation.

- Power. When you're on top, every direction is down. Britain was a status quo power: it had everything it wanted, pretty much. So why embrace change? This is why there were some dissenting voices when HMS Dreadnought was launched: Britain's heavy investments in ironclads would be set at nought, and rival powers given a chance to catch up. America was, by contrast, a rising power, and change was to its advantage.

As I said, none of these explanations are particularly compelling. The United States didn't abandon pursuit of hi-tech weapons just because they didn't help it win in Vietnam. Who (aside from inhabitants of the Foreign Office) would internalise a concern about preserving Britain's global status quo? And different parts of Britain placed different values on better transport: the Scotsman, for example, regularly ran stories about how regional airlines were bringing rural and island Scottish communities into closer contact with civilisation. But I think the difference between British and American attitudes towards the 'superweapon' is, or was, real, so an explanation there must be!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Erik Lund

So the results of my comparison are in. Here is a slightly redacted version of my investigation, which, because of various vicissitudes, is just off being synchronic. (I look at the December 1944 issue of _Aircraft Engineering_, June 1945 issue of _Aviation_, and the October 4th, 1945 issue of _Flight_. That is, if the spam filter will let me. I'll save my summary thoughts for another comment.

Erik Lund

Spam, spam, spam the comments!

This was intended to compare the June 1945 numbers of Aviation, Aircraft Engineering, and Flight, but the limitations of the University of British Columbia collection, which dropped _Flight_ during the war, and a slightly wonky automated recovery system ended me up with the December, 1944 number of Aircraft Engineerin, June 1945 _Aviation_, and October, 1945 number of _Flight._

The December number of AE is 13+41+8 pages inclusive of covers. The front and back sections are advertising.

Front cover is an add for Kayser Ellison Steel, a pencil graphic of the opening of the Menai Straitsw bridge with the information that K.E, had already existed for some months in 1829, but no suggestion that it actually provided steel for this bridge. There follows 6 lines of text and 3 lines of catalogue ads for various K.E. special treatment steels in bars, blacks, forgings and wire, “etc.” It is colourful, but only because printed on green paper.

Inside cover; Vickers Armstrong ad. Full page ads continue for Elektron magnesium, Terry’s Springs, S. Wolf and Co., Jablo, British Aluminium, Sharples oil Purifiers, Ranalah Sheet metalwork, Hopkins Screwing Machines, Encore Plywood, GEC (specifically angling for plant illumination contracts), Smith’s Aircraft Instruments, Taylor-Hobson, Messier Aircraft Equipment, Tecalemit filters, United Steel Companies, Ltd., Serck Radiators, A. P. Newall (purveyor of fine ‘Newalloy’ bolts, ‘Hitensile’ bolts, and ‘Newallastic’ bolts.)

Oppo the title page, half page ads for Rushton’s, a consultant company that appears to specialise in lubrication issues, and Coventry Radiator and Presswork.

Title page has an Equipment and Engineering Co., ad for Magnaflux.

Editorial subjects are: Education for Aeronautics; Tailless Aircraft and Flying Wings; Conditions in Diving; List of Selected Translations; Research in Australia. In the Workplace and Production Section, artilcles on testing lubricants and bearing materials, German radiators, oil tanks and coolers; and enemy spar flanges and extrusions. The regular round up of U.S. patents terminates the issue. An insert in gloss-finished paper has ads for Hiduminium and Fischer Bearings, followed by the Leader, which discusses the ARC’s proposal for an aviation university.

Lockwood Marsh finds the proposals misguided and excessive. Articles are illustrated with black and white photographs and there are more ads of pretty much the same type.

Aviation for June 1945 is thicker than AE at 271 pages, but production values are not entirely out of line with the British paper. The front cover is an ink illustration, but because the colour is mostly background, it does not appear any more colourful than the British, and the subject, although more topical, manages to be equally goofy because it illustrates Sikorsky’s little banana helicopters.

Inside cover is for the Thomson “Vitameter.” The vitameter injects coolant into the carburetto “ONLY WHEN NEEDED,” and will be ideal for postwar car and truck engines.

Opposite is the title page. There are 3 pp of regular departments (news coverage is at the back. Articles: Carrier Aircraft Maintenance is Really Tough; Australian |Boom Hinges on Private Enterprise; How to Estimate Costs in Feeder Airline Operatyions; Novel Presentation Promotes Flight Courses; Designing Tomorrow’s Personal Aircraft; Design Details of Aeronautical Products, Inc, Helicopter; See Prime Role for Gas Turbines in Aircraft of Tomorrow; Three Connection Techniques Solve Aluminum Cable Problems; Induction Heating Speeds Hellcat Production; Trimming Research to the Postwar Pocketbook; Deviation Stickers Quicken Template Changes; Plant-Practice Highlights; For Better Design; Ingenuity of Servicemen Sparks Air Power Maintenance; Successful Overhaul Business Demands Shop Organization; Single-Place Skyhopper Offered by new K.C. company; Blackburn Designs 155-ton Postwar Airliner; Why’s and How’s of Good Airport Turfing; Prefabs show Real Promise for Postwar Hangarage; These Traffic Estimates will Serve Operators and Producers; Distant Reading Compass Takes Lag out of Headings; Superfort Mockup is Ditching Classroom.

The articles are much more literate than the titles, and, in a nice touch, are illustrated by photorealistic cartoons. The discussion is only barely less technical than AE, and falls far short of what _Engineering_ was prepared to print. Ad copy, mostly wrapped around the back pages.

Flight's 4 October 1945 number has a front cover is a two-tone watercolour-type illustration, Blackburn ad highlighting the Firebrand torpedo fighter. Inside cover maintains the colour scheme with less zest, an ad for the Bristol Hercules. Westland ad in pencil opposite. Then Constant Speed Airscrews, a full-page pencil for the Short Shetland, Teclamet, Birmetals, Linread ( bolts), G. Q. Parachutes; Desoutter tools, Dunlop G Suits, KDG Instruments, Electron, Fairey Aviation; total of 7 pages including cover of front matter ads, 14 ads. Follows 29pp of editorial, another 7 pp of ads. Artiles are Leader; The Outlook; Germany To-Day, Vickers Viking, After the “Cease Fire,” Blackburn Firebrand IV, A.T.A. Farewell, ast of a Famous Line, Refuelling in Flight, the Miles Monitor, plus rfegular articles (Here and There, Civil Aviation News, Correspondence and Service Aviation). There is one photographic ad, for a piston, and a small amount of photographic illustration for the articles, including of a three-level Bailey Bridge on an autobahn, included for reasons obscure, but surely interesting to any technically-minded reader.

I think that it is safe to say impressionistically that Flight uses more phtos than either of the monthlies, and that it has more “exciting” material in this and the next issue due to the number of Navy planes requiring attention.

Erik Lund

So, thoughts here. It has long been my impression that while the prewar aviation magazines used aviation for their editorial content, their target market was more nearly automotive buyers. It makes sense, a young, male car buyer was likely to be interested in fighter planes, after all, and was likely to buy the gas, Castrol, piston rings and spark plugs advertised here.

_Aviation_ has perhaps the best example of this, with an ad promoting technology developed for aircraft engines but angling for automotive use on the front cover. As an American ad, we would even expect the most flamboyant use of the English language, and it delivers, although the reward for neologisms in this survey goes to a Glasgow firm, Newall's. (The Newalls? You have to wonder.)

IN terms of overall layout, _Flight_ unexpectedly emerges as the most "modern," with well-laid out ad copy and the title page and Leader buried deep inside the advertising, just like in a modern glossy. (To be fair to _Aviation_, they did that at the height of the war, too. Wonder why they stopped?) On the other hand, _Aviation_ has the best physical values by a long margin. It is longer, better produced, and makes more use of colour --although the difference was not as great as I expected. It also has the most illiterate office staff, although this might be a stylistic or even a processual outcome. (For example, if the page layout was determined before the articles were selected, the copy editors would have had to write article titles to exact page length.)

Technically speaking, the issues of _Aviation_ and _Flight_ examined are both "superweapon" issues. The helicopter is no novelty in June '45, but it is new enough to warrant a coer illustration, and the implications are pretty huge. _Flight_ covers the Navy's show of new 'planes, including the Firebrand and Spearfish, and, more spectacularly, the prototype Sea Vampire, whose first carrier landing is still two months away. (It shows up on Allan Allport's website today.) _Aircraft Engineering_ gives the overwhelming impression that what really matters is contaminated hydraulic fluid. Having heard old-timey engineers complain, I can see their point, but how much less exciting its it possible to get?

So from an internal perspective, it is hard to see a difference between _Flight_ and _Aviation_, while _Aircraft Engineering_ is, if anything, trying to be tedious. If we're going to understand the differing roles of the superweapon in British and American imaginations, we will have to look at reception studies. Maybe there is something to be said for the specialisation of the British technical media market driving audience niches apart?

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks for all that, Erik! Interesting. I'd agree about aviation ads often being aimed at car owners -- I've seen a lot of quarter-page, illustrated ads in 1930s newspapers from Castrol and the like pointing out how the latest air speed record maker used their product. That sort of thing and PR is the only way to understand many of these ads. I mean, how many defence procurement officials look at an ad from Lockheed Martin in Jane's and think, wow, that JSF looks great, maybe we should buy some?

Speaking of ads, here are couple of very good sites about historical British aviation industry ads:

http://www.aviationancestry.com/

http://www.content-delivery.co.uk/aviation/airfields/acads/

Reception studies would be great. But it's much harder to do than content analysis! I'm not sure that professional and semi-professional magazines are the best place to look, though, for the kind of large-scale trends I'm asserting existed. If anyone in Britain was predisposed to thinking technology could solve national problems, it was presumably the engineers. Having said that, this is a good place to mention that I'm definitely not claiming that the British were not inventive or avoided high technology or anything like that. It's more a Clapham omnibus thing.

Alan Allport

Does David Edgerton's book Warfare State talk about popular attitudes towards technology?

Aaron Bady

This comparison really rhymes with what I'm working on right now, which is pre-WWI British East Africa in the Anglo-American imagination, which leads me to make several observations. One is that if we think of the Civil War as the US's WWI (pointless traumatic experience of modern killing technology), the difference in post-facto mythologies is dramatic: WWI was proof that the world was going to hell in a handbasket, while the American civil war (which was arguably on the same scale in terms of stupid bloody pointlessness) was, after the fact, mythologized as a glorious moment of national triumph (David Blight's Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, for instance). And second, when you talk about space, you make your point with respect to national space, but thinking in terms of imperial space would be just as helpful to your argument. Britain was an empire founded on patrolling naval vessels -- which incorporate -- but airplanes structure a different kind of imperial paradigm, one which looks a lot more like the kind of dis-interested control that the US has historically been comfortable with (the monroe doctrine, Cuba, the Phillipines, etc, where the US exerts force and influence, but without actually incorporating the territory in question).

Chris Williams

Hmm, lots to think about. But Aaron, does naval power really give you a different kind of empire from air power? Military power, sure, as the Cairo Conference and air policing demonstrated. Holding the sea - a commons - is a bit like holding the air.

Alan Allport

WWI was proof that the world was going to hell in a handbasket

Without wishing to get into an argument about the 'stupid bloody pointlessness' or not of the First World War, I will say that the popular response/memory of the war was a lot more complicated than that in post-1918 Britain.

Chris Williams

Actually, how about option 4 - censorship? For a large chunk of each war, the US mags were free to spceculate, while the UK ones could not - either the Biffendorf Volestrangling Deathzap was real, in which case it was against the law to talk about it, or it wasn't, in which case you'd look at bit of a fool writing a feature on it. The US had no such problems between 1914 and 1917, and 1939 and 1941.

Jakob

Alan: Warfare State doesn't have much about reception and public perceptions as far as I can remember; England and the Aeroplane has a little more, but it's not really Edgerton's focus; he's more interested in government and expert opinion.

Neil Datson

A few observations.

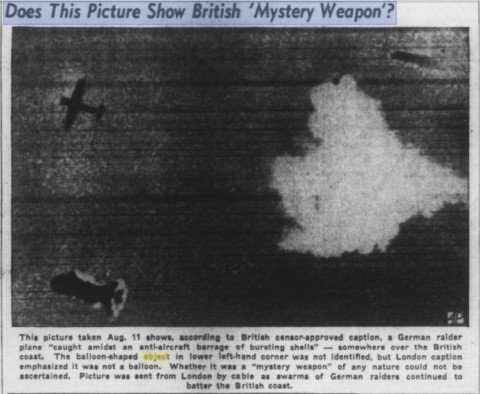

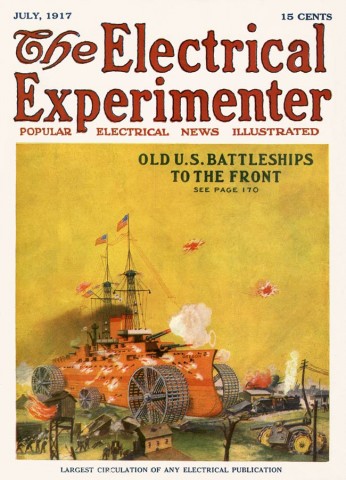

1 Does it help to draw a distinction between 'superweapons' such as the flights of fancy shown on the cover of The Electrical Experimenter, and 'secret weapons' such as the systems hinted at in newspaper reports?

2 It seems that the Experimenter was a fairly serious magazine intended for adults. If that was so, I really can't imagine an equivalent British publication carrying similar covers. Although some of the ideas are at least possible, even prescient, many of them are more suited to schoolboy fantasies. When he landed in New York Charles Dickens (I'm always looking for literary parallels) was astonished by the preference shown by US newspapers for imaginative scandal over accurate reporting. (Judging from our papers now they've only gone downhill.) Was there something fundamentally different in what Britons and Americans looked for in their respective presses?

3 I think there may be something in all three reasons you give, especially the third. For a declining power, developments were not likely to be good news - even their own developments. But I think you can add an important fourth: proximity. The realisation that you too might be killed or maimed by these wretched things. In Britain that realisation really struck home during WWI. Before then, the British probably had a more romantic idea of war than their continental neighbours. In the US, it seems to me, it hasn't really struck home even today. (With that in mind, consider the differences in US attitudes to IRA and INLA terrorism before, and after, the attack on the World Trade Center.)

Probably better stop now as I'm straying way off the matter in hand!

Brett Holman

Post authorI can see the air leading to a different sort of imperial control than the sea. From the sky you'd have this feeling of godlike omniscience and omnipotence, yet there's no direct connection with the colonial peoples, so it's an illusion. The sea only touches the imperial possessions at the coasts, so it's not mistaken for a means of control itself but a highway: there's not the same temptation to do away with boots on the ground in the form of soldiers, police and administrators. That may not be what Aaron's getting at, however!

Chris:

A fair point, but (as Neil notes) I've elided any distinction between superweapons and secret weapons. So on the one hand, some of the Electrical Experimenter covers in the previous post were published after the US entered the war (for example the daft battleships on wheels one). And on the other I'd claim that British writers generally didn't even speculate about possible ideas for new air defence weapons, as opposed to claiming that the government did indeed have such a thing. And that was true in war and peace. (Again it's not that the British weren't inventive, there were plenty of amateur and professional inventors pressing their ideas on the relevant ministries.)

Neil:

That's a good point about the American press. Just think of the Great Moon Hoax; is there anything like that in the history of the British press? Sensation was much more highly prized in the US than in Britain (though the tables may have turned, as you say!) Still, there was a hierarchy of seriousness in the British press too. It may be revealing that it was the Daily Express which ran that article on the giant AA Lee-Enfield and robot interceptor in 1935; it's one of the least stuffy newspapers I've looked at for that period. By the same token, with the phantom airship panics (which was quite a sensational story, actually), The Times picked up the story much later than the Daily Mail for example, and dropped it sooner, clearly holding its nose the whole time. So perhaps we can say that there were more "US-like" areas of British publishing which would be the best places to look for speculation about superweapons.

Christopher Amano-Langtree

If one supposes that the Americans were much more technologically minded than the British because they were a younger country that was not so hidebound in its attitudes one might have an explanation. Conservatism and suspicion of new ideas was very prevalent in Britain at the time (I would say a necessary side-effect of empire). One can look at the welding/riveting issue relating to D steel as a prime example or advances in railway technology which were much more readily accepted on the continent and in America. Not strictly speaking aviation related but an illustration of a general attitude to technology. An overall unwillingness to accept the new would explain the difference very neatly.

Erik Lund

Christopher:

Pardon me for perhaps presuming too much about your sources, but David Brown was not a metallurgist. He was a naval architect. You should not take what he has to say about fastening high-tensile steels too seriously. (Or boilers. Or anti-aircraft fire control.)

He doesn't have anything to say about railroad engineering, but if your library supports it, I would strongly recommend sitting down with the 1930s run of _The Engineer_ and _Engineering_. There's a great deal more to the story of modern railway engineering than the introduction of diesel electrics on American transcontinental runs. There's also a great amateur site devoted to Paxman projects of the war years, including high speed diesels) that I'm going to link too here at the expense of all continuity of argument: http://www.paxmanhistory.org.uk/paxeng34.htm

It does, however, point us to some very real British "superweapons" of World War II. And if I can editorialise, it underlines the real conceptual problem. Motor Gun Boats driven by innovative high-speed diesels, lightweight steam plants or prototype gas turbines are very interesting, but just are not that important to strategists or industrial historians.

Perhaps the takeaway is that we should look for the real superweapons amidst the everyday of war. Who now knows, for example, that the Royal Engineers pioneered RDX in the field? It's not a fact that comes up, largely because the RE used it to cut down on the weight of demolition explosives that they had to carry around. It got into depth charges and torpedoes, and possibly antitank gun propellant by the end of the war, but basically this actual superweapon came into being because the engineers were afraid that they wouldn't be able to blow up all the new concrete bridges erected along German invasion routes into France since the last war. Bo-o-oring!

Narrattives of technological progress may not tell us much about what is actually happening. There is an ideology in the narrative of British conservatism that needs to be inverted. The point of historiography is not to describe the world, but to change it!

Strike that last: I either let "pretending to be young Karl Marx" go to my head, or it's the caffeine talking.

Christopher Amano-Langtree

Whilst I agree with you about Brown the point I was trying to make was that the technology and will did not manifest itself in Britain whereas it did in America. British shipbuilders, marine manufacturers and organisations missed out on such technological advances through a failure of imagination and innate conservatism. The Royal Navy accepted riveting in the JK class destroyers because they acknowledged that it was beyond the technological capacity of British shipbuilders to use welding effectively. One almost might say that because American imagination was more developed American technology developed faster. As for railroad engineering I was thinking on a broader base than diesel electrics (which incidentally took Britain a long time to get right) but also steam and electric technology. Certainly there were exceptions but once again one sees a conservatism and failure in imagination in so many respects. Even in the field of steam technology one sees failure to innovate. What I found instructive was a study of Air Ministry specifications between the wars.

My suggestion is that the British establishment and society was too conservative at a fundamental level to properly exploit technology. The ability was there but it needed a real threat to bring it out. America suffered no such problem and was able to imagine and innovate freely. To some extent Britain was able to imagine but only within certain boundaries which did not pertain in America. I do not consider it accidental that modern science fiction developed in America.

Erik Lund

I agree that it is not coincidental that modern science fiction developed in America. But I also maintain that we need to invert the narrative that you are presenting. The British narrative of technological development _falsely_ presents Britain as being technologically backwards compared with America.

The question is: why?

For example, the high-tensile steels used to make the hull plating of small naval combatants at least since the early 1900s are difficult to weld. There is no getting around this. (Here's a material data sheet for a common post-war DoD high tensile steel specification, HY-80: http://www.suppliersonline.com/propertypages/HY80.asp#General)

Thus, great care has to be taken in introducing new methods. Here's an interesting paper on the work required to prove the DoD's next generation of high-tensile weldable steels after Hy-80, the first not to require preheating: http://ammtiac.alionscience.com/pdf/AMPQ7_3ART09.pdf

All of this of course pertains to postwar designs, but the substance of Brown's criticism is "that it is likely that an all-welded mild steel design would have been lighter as well as cheaper." No footnote is required to launch an enduring criticism of what was, in fact, a design of almost heroic complexity. (The Js and Ks, apart from introducing a 2-boiler installation requiring the production of 20,000hp/boiler, used longitudinal framing in the main part of the hull, joined to transverse framing in bow and stern sections --essentially, transverse frames under the guns, longitudinal in the way of machinery. You can see why the designers were careful about the joins, and why describing these designs as "conservative" is wildly inappropriate.

On the "conservatism" of British railway practice, I am afraid I shall need substantive counterexamples to, say,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Turbomotive

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Underground_battery-electric_locomotives

(Note the introduction of the metadyne)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LNER_4468_Mallard

(Good at the conventional stuff, too)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Rail_10100

(Not "conservative," whatever else you might say. Maybe it would even have been pursued were it not for..)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napier_Deltic

This is fun!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Rail_Class_73

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/City_and_South_London_Railway

(Maybe Martin Wiener is right and the British forgot to be innovative sometime between 1892 and 1935, admittedly)

(Following a 1940 first run at the concept)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gas_turbine-electric_locomotive#United_Kingdom

(Brown Boveri had been trying to sell this concept since at least 1938. Of course one may argue that this is a Swiss firm, even if the engineering was done in the U.K.)

Erik Lund

I think I may have found the poor spam filter's limits. Not to multiply examples endlessly, it is hard to write about "conservative" British railway engineering practice seriously after noticing the Deltic. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napier_Deltic

Christopher Amano-Langtree

Unfortunately the evidence I found did not indicate a problem with the difficulties of welding per se but an unwillingness to solve them among industry. I should here confess that I wrote 'The Kellys - British JKN Class Destroyers of World War II' and would have liked to have included the full discussion on D steel in the book but was preclulded from this by considerations of space. There was also considerable resistance to the principle of longitudinal construction itself from the shipyards and whilst the navy was able to force this method of construction through it balked at trying to introduce all welded hulls - something they considered desirable.

The turbomotive itself was a wonderful device but how many were there? Only one and despite its obvious advantages it was never expanded beyond this single example. This was despite the fact that it had demonstrable advantages. Here though I would like to argue examples with you (Class 74 for example) but I am concious of the fact that we are straying from the subject of aviation so you will forgive me if I don't respond to your comprehensive research. However, I will bring up some examples from the world of aviation, the Overstrand which entered service in 1936 when the Americans were introducing the B10. Certainly it had a power operated turret but so did the B10. One struggles to find airliners to match the Electra, DC2 and DC3, aluminium monoplanes powered by good engines. I would push the barren period of lack of innovation to 1937 though. Only then did you see us start to catch up and introduce technology on a par with the US.

Erik Lund

Christopher:

There was no "conservatism" at work in the continuing use of rivets to join high tensile D steel parts. Type D steel could not be successfully welded at the time, at least in shipyard conditions. Low carbon steels are, and continue to be, funny that way. Longitudinal and transverse framing represent real construction alternatives: longitudinal framing uses weight more efficiently, is cheaper, and gives a fairer form; transverse framing preserves more internal volume. (http://books.google.ca/books?id=y2GT5JyVrzAC&pg=PA197&lpg=PA197&dq=transverse+framing&source=bl&ots=wvNJLVrbiA&sig=hMkUt-QOSt1z3VoMAhJTa75WcG4&hl=en&ei=UIEiS4G4EojgtgOpjsj8Cw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CAoQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=transverse%20framing&f=false)

My understanding is also, at least at the time, the efficiencies of longitudinal framing were only really recovered in larger ships. The J/K/Ns were much bigger than earlier British DDs, except for the Tribals.

Additionally, the J/K/Ns were, as you know, very difficult designs due to the need to fit in very high elevation angles for the 4.7" guns. Consequentially, there were very deep gunwell cut-outs in the areas of the ships given transverse framing. I imagine that this was a factor in their very complex framing schemes.

By the way, contra Wikipedia, the B-10 did not have a powered gun turret.

http://home.att.net/~jbaugher2/b10.html

The first satisfactory American power turrets (which appeared as late as 1942) used Amplidynes, the GE-patented electrical control system that in no way was just a copy of Pestarini's Metadyne ripped off by Bell Labs after Pestarini tried to sell them American rights. Irving Holley wrote on this quite a bit, although he missed the patent imbroglio. I admittedly may be making too much of this last, but in my head I am still arguing with Correlli Barnett over Very Important Issues.

Christopher Amano-Langtree

Here I am afraid I must correct you on one or two points. The JKN class did not have high elevation angles, the maximum of their twin MK XIX mount being 40 degrees elevation. Certainly gunwells were considered and even trialed on Bulldog but not proceeded with on these ships which were flush decked around the mounts. Time was a significant factor with mounts taking longer to design and construct than the ships themselves. The Royal Navy designers proved incapable of solving this issue pre-war but American designers had done so producing the 5/38 inch with an elevation of 80 degrees (I believe).

Longitudinal construction did indeed prove to be lighter (but this was only a factor when welding was employed) but significantly it also imparted greater strength in the bending moment and hence buckling. It was not new technology havng previously been used for one British destroyer (the name escapes me though). However, the reason for introducing it was not its strength or lightness but because of the need to keep the silhouette of destroyers low. However, the Ships Covers indicate clearly that the decision to go with riveted hulls was because it was felt that British shipbuilders were incapable of welding. The belief in the constructors department was that American shipbuilders had already solved this problem. Welding was preferred on the grounds of lightness and greater structural integrity but was unavailable.

I hadn't realised that the B10's turret was unpowered but otherwise it was still technologically a more advanced and capable design than the Overstrand. It did show a superior and more modern approach.

Erik Lund

Fair enough on the corrections, Chris. I was assuming too much on the gunwells issue.

At the same time, I do not think that it is fair to compare the American 5"38 with British 4.7"/50s, however. Without delving into difficult-to-make comparisons, the latter was heavier, longer, had higher breech pressures, and fired a heavier shell.

Also, British shipbuilders were perfectly capable of welding warships: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Seagull_(J85). The issue here is "D" type low-carbon, low-alloy, high tensile steel. Such steels are hard to weld. Sometimes, you can't weld them.

But you can blame other people for not figuring out how to weld the steel that you required them to use in a construction, at least when people are criticising you for not producing American-style welded warships. Here's another discussion of, amongst other things, the problems in welding specialty steels.

http://books.google.ca/books?id=AquJOfZ1tNEC&pg=PA8&lpg=PA8&dq=welded+warships&source=bl&ots=01pogToL7n&sig=toCoP7PSZfAk_JW7Y8d0_3ie67o&hl=en&ei=J_IjS5OyJJCiswOfnsXgDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CA0Q6AEwATge#v=onepage&q=welded%20warships&f=false

Strangely, you'll not hear _Americans_ crowing about their magnificent achievement of all-welded pre WWII destroyers. So it is hard to find an online discussion. I bet I won't have the same problems with _Trans. SNAME_ whenever I can get to the library next. In the mean time, a rivetter recalls working on USS Laffey at Bath Iron Works: http://www.laffey.org/clarence_dargie_courtesy_ari_pho.htm

Again, we have some issues with the J/K/N destroyers, which fell short of the extraordinary ambitions of the initial proposal in the usual "failing forward" way of defence projects. From the standpoint of Brett's project, what is interesting is that the designers did not say, "oh, well, we didn't get everything we wanted in this project. Next year's class will be better." They said, often simply making up the facts as they went along, "we've been thwarted by innate British technological conservatism. The Americans do it better."

So the question is, _why_ is this the story told in Britain, in sharp contrast to the American story, which doesn't even think to bring out the supposedly backward use of rivets in American destroyers of World War II? (If we bring up machinery, this becomes even more apparent.)

And, yes, the B10 looks a great deal more modern than the Overstrand. So does the Beardmore Inflexible (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beardmore_Inflexible) and the Vickers Vireo (http://www.aviastar.org/air/england/vickers_vireo.php). Corrugated metal construction methods achieved some impressively modern-looking aircraft in this era, but the method was a dead end.

Christopher Amano-Langtree

I did in fact attempt a comparison between the 5/38 and 4.7". They are broadly similar weapons and whilst shell weight isn't really a factor, rate of fire and Dual Purpose capacity are and these are what give the 5/38 it's edge. What is important for dual purpose capacity is not the gun itself but the mount and here the British failed through conservatism and a lack of imagination.

I rather feel that we must not lose sight of the narrative of the times - technology at the time in Britain was a 'trade' not a profession. In other words it was second class. Technology in America was a new and exciting development and definitely not second class. The American imagination embraced technology whilst the British imagination was more taken up with empire and turning out 'good chaps' who were not necessarily the greatest thinkers or most innovatory of people. So a monoplane bomber with power operated turrets was a possibility but was not developed. Even with corrugated surfaces and no power operated turrets the B10 was a far superior machine to the Overstrand, able to carry a greater load further and faster. I would submit this was a triumph of the American imagination over the British. Of course this is an over-simplification but it is a function of decaying empires that they stifle innovatory impulses and fail to exploit the future. This is very much the case with Britian. I mentioned modern science fiction developing in America, the popular fiction in the UK was tales of imperial derring-do. This I would suggest is significant and illustrates the difference in imaginations very nicely.

Erik Lund

Christopher, I'll first follow your lead by address our host's interests before I start cramming numbers with this allegorical retelling of my position:

So your host at the party obviously has some kind of matchmaking agenda, and keeps introducing you to people of the applicable sex, and being the person that person is, throwing the two of you into a conversation about sex. Person a) is casual and relaxed, talking about their sex life with multiple partners without a care in the world before wandering off to the buffet table; person (b) stumbles, blushes, can't meet your gaze, changes the subject, and then tries to monopolise your attention with their best material while unconsciously fidgetting with their clothes and hair before suddenly fleeing to the bathroom to fix their wardrobe.

So, which of (a) or (b) is more attracted to you?

(a) America, and technology, (b) Britain, and technology.

On the 4.7"50 versus the 5"/38. It will be noted that by definition the barrel of the former is 235" long, of the latter, 190". I could talk about weights (3.2 tons with housing versus 3.35, per Cambbell, _Naval Weapons of World War II_, admittedly for the Mark XI), recoils and such, but I think the fact that the former is more than a yard longer than the latter is a pretty big difference when we consider the difference in torque required to rotate the former at high elevations, versus the latter. In short, rotating the muzzle of a gun that is 5% heavier overall and 45" further away from the breech at high angles puts more load on the deck structure.

And are you sure that the comparison between the Overstrand and B-10 is entirely appropriate? The Overstrand was a minimal development of an 8 year old aircraft when it entered service in 1936. Comparing it to the Fairey Hendon would yield a very different picture: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairey_Hendon

If we are bound to compare the two, take a look at the power-to-weight and wing loading of the two aircraft, both heavily in favour of the Overstrand. This isn't too surprising in comparing a biplane to a monoplane, but are we looking at the right numbers?

The specification numbers (all right, mainly speed) for the B-10 look very impressive, but they should. I've found them in an advertising brochure. Now, it may be that Martin chose to use its official USAAC figures for its international advertising, but in the context of the times, that would be like sending your salesmen to a gun fight armed with knives.

So, are they correct? I've only found one contradiction googling, but my time is not unlimited, and the contradiction is a doozy: the listed landing speed of 62mph was, in fact, an "acceptable" landing speed in initial trials of 71mph --down from over 90 in the prototype offered to the USAAC! Planes could go very fast in 1933, as long as you sacrifice other things, such as safe landing speeds. With contemporary aircraft speed ranges, it was not uncommon for a 1mph inrease in landing speed to correspond to as much as a 3mph increase in top speed. So relaxing the safety requirement on the air field could have a very large effect on recorded maximum speed.

Not that I believe that the B-10 actually achieved a 200mph+ top speed in service, any more than the Blenheim was a 300mph bomber.

http://www.hyperscale.com/features/2000/b10bcd_1.htm

Christopher Amano-Langtree

Given that both mounts were power operated, the torque from the extra length would not be a significant factor. No, there is another factor as to why the 4.7" was not dual purpose and I would suggest that this pertains to the fundemental treatment of the air threat by the Royal Navy. This in turn leads to a failure to design a suitable mount (and such mounts could be designed). Neither the USN or for that matter the IJN had this blockage and both were able to produce successful mounts.

The Fairey Hendon might indeed be a better comparison but once again we run into the failure of imagination. The Hendon took a long time to get into service (I have read six years development) and then was handicapped by its non-retractable undercarriage. The point about the B10 was not that it was a super bomber but that it was better than its British equivalents. Certainly we can find areas where the Overstrand was superior (it was more manoueverable for example) but these didn't really have any impact on its purpose as a bomber. Neither machine would have prospered in WW2 (and in fact Dutch B10s were rapidly shown to be totally obsolete) but at the time they were built we can see a reliance on an outdated design philosophy (Overstrand) and a willingness to embrace the new (B10). The B10 was the way forward and the Americans realised this before the British came to a similar realisation.

JDK

I think Brett's made a very interesting observation about differing 'national imaginations' in the UK and US, and it would be a fascinating area to try and explore evidence for to develop further than the excellent work Brett's done so far. Critically, it would take an approach prepared to compare like-for-like and to follow the evidence, rather than pushing a preferential agenda, where, as in all forms of national cliché and xenophobe's other works, it's all too easy to stack the deck.

I find Christopher's post comparing the excitement of engineering in the US against Britain's jolly good chaps running an empire bang-on - and supported by the children's literature of the period I'm familiar with (an area I'm particularly interested in, although I don't propose it's a scientific sample, just one built in growing up in the UK). Coming back to Brett's idea, the best that was happening for kids in books on aviation was lectures on how brilliant everything that had been built was, and how your role would be maintaining the Empire; while in the US there was a lot more you could be innovating tomorrow.

So I'm continually impressed at the further examples we are getting from Eric in his valiant but doomed effort to show innovation and technological superiority in the inter-war British world.

Both the Hendon and the Overstrand were obsolete in comparison to the Martin B-10. The fact that the B-10 was using new technology (again Eric's muddling the nature of the structure - corrugation or not is irrelevant - it's the stressed skin that counts - or not) while Fairey and Boulton Paul were using the fag end of the fabric covered structure era. One could debate the right time for all-metal stressed-skin structures - beyond debate is that Britain, by taking overall fabric covering into W.W.II, retained obsolete technology well past its sell by date. The fact that they tried to bring a fabric covered strategic bomber into service in 1944 (the Vickers Armstrong Windsor - an abortion, at best and, like the whole post-Wellington geodetic factories a disgraceful waste of effort) shows how reluctant they were to let-go a thoroughly bad idea.

(The turrets are a red herring on the Overstrand and B-10. Powered or not, at this stage they were simply providing aiming assistance (and more crucially wind-protection) to the gunner at the speeds faced. The fact that the British one was powered and that the American counterbalanced is actually irrelevant - their performance was, as far as I can establish comparable. Critically, they were both under gunned and on the wrong end.)

Erik Lund said: ... the listed landing speed of 62mph was, in fact, an “acceptable” landing speed in initial trials of 71mph –down from over 90 in the prototype offered to the USAAC! Planes could go very fast in 1933, as long as you sacrifice other things, such as safe landing speeds.

Erik, you ARE C.G. 'land-slowly-don't-crash-and-burn-up' Grey and I claim my five pounds!

I'd be interested in your idea of what a 'safe' landing speed is, and more importantly, if you've ever discussed it with an aviator - particularly aviators flying 1930s aircraft (today) - because it has nothing to do with your comments above regarding faster or slower.

I'm glad Erik nails his colours to the mast, because it shows us what we are going to get. To do the same, my colours are to follow the evidence. I've no preference to any beliefs technology or imagination in the 1930s, it's just something that becomes all-too-obvious when you study the era.

Regards,

JDK

One way of making a reasonable like-for-like comparison would be to take a run of the British Practical Mechanics and compare it to the American Popular Mechanics, say in the 1930s. Not being familiar in detail with both, there may be a different editorial thrust or anticipated readership, but I suspect that you'd have a pretty good peer group, and I'm sure some interesting (and amusing) comparisons could be made. You might learn something, too.

I reckon it would be a great way of spending a weekend, or longer, but I don't think I can find the funding!

Regards

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Practical_Mechanics

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popular_Mechanics

Chris Williams

C A-L wrote:

" steam and electric technology. Certainly there were exceptions but once again one sees a conservatism and failure in imagination in so many respects. Even in the field of steam technology one sees failure to innovate."

Forget the one-offs like the Turbomotive - instead examine the career of Oliver Bulleid, notably the BoB and Q1 classes. The reason that their design features didn't catch on in the 1950s is that they were not economical. "Have the most advanced technology at all times" is not the way to run a railway.

C A-L: "I rather feel that we must not lose sight of the narrative of the times – technology at the time in Britain was a ‘trade’ not a profession. In other words it was second class. Technology in America was a new and exciting development and definitely not second class."

The fact that this was the narrative of the times doesn't mean that it was the reality of the times. In fact, it can be taken as evidence for the reverse of this. See Edgerton for this. I like Marty Wiener, and I agree with almost every word in his second, third and fourth books. But not the first one.

JDK - I'll see your collection of children's literature and raise mine: the _Eagle_ and Neville Duke were pretty clear that we'd be commuting to Australia by rocket by now.

Christopher Amano-Langtree

I take it you mean the Merchant Navy, West Country and BoB classes? They were built in significant numbers but their design features were not practical. Chain drive in an oil bath was a difficult technology and maintenance problems rather than economics was the reason for their rebuilding. But given that the path of development was away from steam one has to ask why they were built in the first place. The Q1 class was a very successful steam freight locomotive which looked 'odd'. A lot of the objections to it were based on the fact it didn't look like a steam locomotive should.

The narrative is often the reality and this shouldn't be overlooked. How cultures see themselves defines how they are to a large extent. Britain was an Imperial nation and the narratives and reality matched each other. The Imperial imperative is stability and conservatism - change is not good for empires. The fact is that technology was second class in Britain between the wars. In fact I would go further and say that it has always been so.

Chris Williams

Christopher, have you ever read 'England and the Aeroplane' and 'Warfare State', both by David Edgerton? I found them both highly convincing - you obviously less so. What do you think is wrong with the argument in them?

Christopher Amano-Langtree

If a short answer is acceptable - incompleteness and selectivity. He is certainly right in identifying warfare as an important driver in English history - but wait I thought this was known anyway? He doesn't really command his material and demonstrates little understanding of the subject - his listing of obsolescent designs as an attempt to demonstrate the virility of the British aerospace industry is a nice illustration of this point. I very sincerely doubt that he has any understanding of Empire either - his writings have not demonstrated any such knowledge. I would say that any attempt to understand England needs to be firmly grounded in a knowledge of the Imperial state. Edgerton does not understand this. I appreciate you will probably not agree with me but these are the reasons.

Chris Williams

That's actually quite general, Christopher. _What_ does he get wrong?

Which aspects of the Imperial state do you consider relevant for this debate? How was an Empire held together by Cable and Wireless, flying boats and (oops) airships 'backward'? What's the standard of 'progressiveness' that you're measuring it against?

JDK

Dear Chris,

I was referring to the inter-war period, particularly the 1930s. The Eagle and Neville Duke were of course the bright new world of the 'modern Elizabethans'. A different era and discussion, I suggest. In aviation, any chances of major British postwar success was busted by bankruptcy and political disaster, rather than paucity of imagination or technical know-how. However, to raise you again ;-) for the worm in the apple in that era would be the musings of Nigel Molesworth, who saw through the whole Whizz for Atomms thing.

* * *

As Brett knows from my frequent rants, as a journalist, with one foot in the research camp and the other in real-world aircraft operation and preservation, I'm equally frustrated by practical engineer and pilots lack of academic or historical understanding at times, and by academic book-reference throwing - rather than getting out and experiencing the things debated. Hence my lack of worthy citations here, because they aren't in libraries.

I'm not aware of anyone driving both British and American W.W.II era destroyers or steam locomotives, but there are plenty of people familiar with hands on experience of British and American aircraft of the era. As one would expect, there is a home-team bias in the US and UK, however it is interesting off these turfs - such as in Canada, New Zealand and Australia, as well as France, Belgium and Germany. Again, leaving the local product out of the equation, from my experience discussing aviation technology and making the same go - from the hangar or in the air - by engineers, restorers and pilots that there is an almost 100% currency that British designs are over-complex 'do things the hard way' (quote from today by a naval engineer acting as our guide on HMAS Castlemaine) and while occasionally brilliant and often effective, given a choice, an American equivalent (while not perfect) is usually better at the job, and easier to use.

I can't put on this blog what Ralph Cusack says about the 'typically Pommie' design ideas in the the Bristol Beaufort he is restoring in Queensland - it's not nice, and if it still had the British (Bristol) engines, it wouldn't have a chance of flying. (The unnecessary ironmongery in the undercarriage doors is a revelation of pointlessness.) Discussing the Comet racer replica with the pilot Robin Reid at Oshkosh this summer was illuminating in some of the designs shortcomings - excusable - sometimes necessary - in an all-out racer, but there were better solutions to de Havilland's problems, at the time. However DH 'knew best' - as is demonstrable when you account the failures of their types (DH-86, DH-87 and DH-91 - all with significant technical failures), actually, Geoffrey didn't.

Part of that was a separation of engineering understanding from design - as GDH exhibited with his frequent redrawing on the board over designers work for 'better looks' in 'his' aeroplanes, and other factors up for debate. However Camm's having to use biplane technology in the Hurricane because Hawker's British factories couldn't switch to stressed skin construction - while in less time American factories covered a lot more ground a lot more quickly a few years later - 36-39 for Hawker to need to keep fabric wings on Hurricanes, 41-5 for an production engineering revolution in the US.

It is unarguable that many British aircraft manufacturers hung on to old techniques, production and design far to long in the 1930s (Hawker, Supermarine, Vickers Armstrong) and if there hadn't been the good enough Hurricane and the remarkable but technically serendipitously developable Spitfire, they wouldn't have got past summer 1940.

So I don't care about postulated 'narratives' being reversible as suggested above, and I'm wary of loading performance figures of brochure data with your preferred items - either way. There's many great British aircraft, and lots of American duds, but as industries, in the 1930s and early 1940s the problems in British factories, in developing practical answers to current issues and having a realistic idea of how to move from fancy hand building to real industrial production - they were a mess, and it was a close run thing.

Leave that aside, and look at thirties airliners. The successes and failures of the era are stark.

Then take the comparative development of Bristol's Britain First (itself a response to another newspaper magnate's new American Lockheed 12 liner) into the Bristol Blenheim and then contrast it to Lockheed's transformation of the Model 14 into the Hudson. Airliner into bomber the hard way or the quick way. Neither were perfect, but Lockheed iterated and innovated from there - and Bristol came up with the Bisley and worse. (The Beau was a beau, to be fair.)

I grew up with the Empire's industrial revolution growing to save the world in the Battle of Britain. Being told when I travelled outside the UK that actually British machinery of the era was a joke to many overseas users was a shock, but I'm still looking for credible evidence to show otherwise. I'm pitching the examples strong here, and there's more shades in the detail and the big picture, but load it how you will, if you follow the technological, production and utility data without stacking it, the scales bump down the same way every time.

Museums are too nice to say 'this aircraft was a d o g'. They offer some, but not the bad news of the stories. The technical knowledge isn't usually on show.

Paper holds much of the story, but not all, nor any of some crucial insights. Tell me where you are in the world, and I'll tell you where you can go to meet and discuss aircraft of this era with people how know them and make them go. (There are engineering-operational reasons there are no Dragon Rapides flying in Canada, but there are Lockheed Electras, for instance.) No footnotes, perhaps, but a worthwhile complimentary source of knowledge.

Regards,

Chris Williams

Ta J. I'm in the English midlands, and I only need to go up the road to look at an example of what looks to my eye like unnecessary British complexity: a DH Blue Streak, which in this case is stood next to a far more svelte Thor-Agena.

I accept that the UK airliner industry in the 1930s was a long way behind that of the US. But how much of this can be explained by two factors

1) geography created a greater demand for airliners.

2) resultant economies of scale between a larger economy and a smaller one, in an industry where they mattered very much.

?

I don't think that we need to postulate some British technophobia to explain this. Indeed, although I'd need to see the things to be sure, I wonder if the undoubted engineering failures that you talk about above were actually products of a culture which liked complex technology _too much_.

There's probably something important here about skills: perhaps the British were more likely than the Americans to substitute skilled labour (designer, creator, operator, fitter) for capital? But if so (and it was certainly the case in the C19th, as Habbakuk has shown) this can be explained by economic factors (cheaper labour) rather than fear of evil technology.

Erik Lund

I'd like to say that as a Canadian, my viewpoint is balanced between big brother to the south and the old Imperial master across the poind, but that's Pearsonian rubbish, and my anti-American anglophilia came in my mother's milk.

That said, I came to this argument the hard way, starting with Barnettian outrage at the way that the "two cultures" divide ruined the British Empire and far too much experience with the vicissitudes of British-style high speed motorcycle engines (presumably my Japanese machines were at least more reliable than British twins). It was the difficulty in finding actual evidence to support Barnett, and the growing realisation that he made no intuitive sense that changed my mind.

To review that intuitive argument:

Britain had between the wars, the larger military aviation budget, and thus by far the larger aviation establishment. There was more, and more thorough R&D spending, and America had nothing like the AID, RAF Halton, or Martlesham. Because it didn't, and couldn't, spend as much on military aviation. Obviously American civil aviation was healthier in many respects than British. But that by itself doesn't tell us very much. Canada and Australia had the largest cargo aviation sectors, because it was cost effective to fly into gold fields, and neither country had aviation industries worth mentioning.

Now, government and private sector spending reflects the health of the broader economy. Britain started the interwar with a shallow economic recovery, lapsed into a recession in 1928 (I think), got spectacularly worse in 1931, and moved into postive growth in 1933. The United States, more simply, had a spectacular 1920s and a difficult 1930s. The cusp was marked, as these things often are, by an investment bubble that funnelled almost 2 billion dollars into aviation manufacture. Given the 5 year lag in aircraft development that applies even to the B-10 in its complex history, this pretty much accounts for what we see here. No-one compares the Curtiss Condor to the Atalanta, or the (first) DC-5 to the DH-95.

I would argue that this is because we do not need to invoke arcana of national culture, or suppose that British engineers are somehow unable to design proper technology. It is, quite simply, investment in, output out. German, British, American, Turkmeni, the output will be equally effective within an upside/downside of (say, pulling a number out of his hat to apply to a distinctly vague concept) 10% better or worse than ideal.

That doesn't mean that we don't have a very different picture of things. Because things are always in danger of fetishisation. Thank you, Suzuki, for giving me the GT500, the most beautiful, most frustrating thing in my life so far. That sentimment suggests that I, personally, need to spend more time around girls, but also that the conjunction of machine and emotive attachment is not always rational.

Take skinning, for example. We're agreed that Martin used a technology of skinning that didn't work, and that anyway since the B-10 used fabric-covered control surfaces, while the Overstrand was all-metal apart from its skinning, that the difference between the two planes lies mostly in the value we put on the idea of metal-skinning in its own right. So perhaps I should point out that the fabric was doped with a plasticised celluloid that represents cutting edge plastics technology. The Overstrand used high tech plastic skinning!

Now, I do not consider that legitimate rhetoric. I consider that fetishisation, turned on its head.

Erik Lund

So here, again, the thesis on which I stand and fall. There is no "national cultural" difference in approaches to technology. That said, there may be a national economic difference. British designers tend to emphasise high value added products, Americans do the mass-production thing better. British factories can't import a dollar's worth of Swedish iron ore, do 10 cents worth of improvements on it, and then compete with Detroit for a sale in Des Moines. Or even Sydney.

That doesn't make military equipment a better comparison, because the United States, very luckilly for it, got to spend less on guns in the interwar period.

It does make those comparisons which are made, problematic, because they lead us inevitably to argue either essential differences in national character, or to claim that "culture" can be like some kind of wall between the human being and their tool, a claim that I believe goes directly to what makes humans human. (That is, it becomes an issue for ethics as well as economics.)

So it is, to my mind, useful to deconstruct these comparisons to pre-empt theses about the nature of humanity that I believe cannot stand on their own merits.

As Christopher writes, the ultimate reason that British destroyers did not carry true dual-purpose main armament is that the Admiralty chose not to do so. Comparing the weight, length, projectile size (hence structural work done in rotating, elevating and firing the gun) tells us about the nature of the choice. The 4.7"/50 was heavier than a 5"/38, and it was heavier because it had a greater chance of hitting a surface target. The Admiralty made a different choice about balancing surface action against air action then did the Navy Department.

Why? Did they lack airmindedness? No, that is the narrative again, the narrative that works functionally to drive British industry to high value added investment when it might otherwise sit back and lose competitive advantage.

Here's my explanation, which turns on endless discussions of manning laid out in the design covers in Marsh, _British Destroyers_, but just as applicable to the dreadnought revolution. The Admiralty war gamers had come up with an ideal number of destroyers, balanced against demand for cruisers, battleships, and so on. Now, it had to allocate sailors, which were in limited supply, for reasons that go to the heart of the problem.

Giving main guns an 80 degree elevation is a good idea in its own right. But it meant increasing the size of a destroyer. Every increase in size has a knock-on effect on machinery that is particularly severed because destroyers go very fast indeed. More machinery means more fuel, which means more size, which means more...

So say we can contain the increase at 10 men. Reasonable, right? No: over the whole Fleet, that meant investing an additional 1% of all available sailors in the destroyer fleet, taking them away from other branches.

But the problem wasn't one of providing destroyers with high angle AA fire, but one of allowing destroyers to contribute to fleet AA screening. Destroyers are not much at risk from level bombing.

So if it takes 125 men to man a specialised AA escort, then you can have a _Bittern_ and a _J_ for 315 men, vice two _Js_ for 365.

The American interwar Navy Department would never make this argument. It has more men interested in being sailors than it can take onboard. Its concern is that Congress will only fund so many destroyers.

This is, on the contrary, the logic of a military that is as large as a nation can afford. Try to increase the manpower of the navy, and the Admiralty will just be going into the labour market and offering inflationary rates of pay. That is not going to work. Thus, specialisation.

Jakob

Whilst I agree with Christopher A-L that some of Edgerton's work is somewhat selective, in the works mentioned he is being intentionally polemical; I'm with Chris Williams in essentially agreeing with him.

The problem for Wiener and Barnett's thesis is that it cannot explain such facts as the UK's development of technologies such as radar and the jet engine; both of which were pioneered before the war. The UK probably spent more than any other nation in the world on defence in the interwar period, and its aviation industry was the largest exporter of military aircraft in the world. Clearly someone thought its products were worth buying. It made the move to stressed-skinned structures somewhat later than competitors, but it had caught up by the end of the interwar period.

As Erik has argued elsewhere, much of the 'backwardness' of British interwar airline design was due to the operating environment; The HP 42 and the Empire Class (for example) were competing against trains and steamships, so the emphasis on luxury and load over speed is more a feature of the market than of reactionary willfulness.

This isn't to suggest that there weren't also cultural differences that affected the design process. As Chris pointed out, there were historical differences in labour costs that affected the choice of labour-intensive production methods. I'd agree with him that there was probably a cultural bias in UK engineering that favoured 'clever,' possibly overly complex and individual solutions; I'd argue that this can be linked back to the 19th-century and the dominance of the individualistic consultant engineer.

In the production arena, the most recent stuff I've read suggests that almost all of the productivity difference between the US and UK aircraft industry (at least during the war) was due to the larger US production runs. On the other hand, the US attempts to use pure mass production techniques were generally failures; the nature of production was such that runs were not long enough to gain the benefits (unlike for tanks and trucks.)

Christopher Amano-Langtree

I would say we have to be careful about referring to complex technological solutions. French solutions were more technologically advanced than the British ones and whilst this succeeded in some respects it led to big problems in other respects. With regard to destroyers French ships were over-engineered and their mounts and ammunition feed not reliable. So it is dangerous to talk about British technological solutions being too advanced - rather they were very conservative. An example here is the two/three boiler debate which took 15 years to solve. Additives to boiler feed water were another issue in which British conservatism ensured we lagged behind the US. Unfortunately, the nature of conservatism is a reluctance to change when change is necessary. We have to remember that both the Americans and Japanese solved the problems of dual purpose mounts which the British did not. This alone negates any argument that a non DP mount was a concious choice between priorities. The struggles to get the Oerlikon adopted should remove any thoughts that people were making choices between differing but equal options.

With regard to civil aviation we have also to look at the attitudes of the buyers of the products. Imperial Airways was conservative in its selection policy and in fact one can also point to Lufthansa. Here we have an airline made up of modern monoplane aircraft which whilst not as good as the American examples surpassed the British. The argument that speed and luxury do not go together is spruious I'm afraid - in fact a faster journey is often the more comfortable one. One also sees this with French developments - their airliners were more modern as well. One thing that struck me was retractable undercarriage on biplanes. Try as I might I could not find any examples in British aviation despite its obvious advantages. Yet we see biplanes in America with retractable undercarriage. A small point admittedly but one which ideally illustrates the conservatism prevalent in the industry.

JDK

Interesting, Gentlemen,

I don't propose to offer any 'why' which is being hotly debated, and I'm curious that arguing the toss about two (or three or more) author's versions of history is more important than getting some of the basic facts right.

The discussion above being built on data that isn't actually correct and arguing about theses of people who aren't here isn't inspiring towards accepting the proposed further views, which, for all I know may be sound in themselves. I'm not inspired to go and look up Barnett or Edgerton given the argument here is based on plain wrong understanding of what the aircraft could do and how they work.

Cash - I don't see that anyone's size of spend has any automatic corrolation with efficiency. You can always spend more and get an inferior product. Britain may or may not have spent more, it often got an inferior product in the thirties as an airliner or warplane, as in the examples I cited.

Stressed skin - Despite Erik's most interesting understanding of it, it's not a nice option that was too early or failed.

It is important to understand what stressed skin construction is and how it works. Erik, I didn't "agree that Martin used a technology of skinning that didn’t work" because that's just not true. What Martin used was the new, technology that everyone had to adopt soon after - fabric covered control surfaces and all. It was simply better at the job for a bomber than the Overstrand's (or the Hendon)'s fabric covering.

I don't propose to offer 'alclad 101', but a discussion with an aircraft engineer familiar with that period - such as one working in aircraft restoration - would evidently have a bit more reality than some of the above.

Jakob said Britain "...made the move to stressed-skinned structures somewhat later than competitors, but it had caught up by the end of the interwar period."

Er, no, it didn't. Vickers Armstrong factories were locked into Barnes Wallis' fabric covered geodetic construction, producing the Wellington for far too long, the useless as a bomber Warwick (first flight 1939) and the unbelievable bad Windsor later still. VA weren't some second rate armament producer, but a key part of Britain's 'greatest' arms combinations.

Secondly in 1939 Hawker were desperately developing the stressed skin Hurricane wing and were replacing the completely obsolete fabric covered wings on the aircraft in service right up into 1940.

Whatever way you cut it, one of Britain's primary bomber and fighter producers each had not (and in VA case in never really did) make the switch to modern construction. One must also point at the cost and lost design time in producing two sets of wings for a single fighter type, not to mention the effort Hawker put in to keep the fabric on at 350mph+. It's a fabric covering process quite unlike any other, which is a clue you are taking your process too far. (See the Hurricane in London's Science Museum for the only remaining example of the Hurricane's fabric wing - as used in the Battle of Britain of 1940, by the way - and my friend Melvyn Hiscock's book on the type's construction.)

I'm interested in the lack of looking at 'why' for individual data rather than dragging them into a pile to support a bigger statement. Erik says "Canada and Australia had the largest cargo aviation sectors, because it was cost effective to fly into gold fields, and neither country had aviation industries worth mentioning."

Why, Erik? Because they didn't have the industrialisation needed, and as Dominions the SBAC and UK government wouldn't let them. Have a look at the history of Australia's CAC and the battle Canada had to go through with the British to produce Hurricanes to protect Britain with. (Incidentally it's notable that the maritime patrol type Britain offered Canada to produce was the Vickers Supermarine Stanraer, while the US offered the PBY or Catalina. I love the Stranny, I wrote a book about it, but it was obsolete when offered for production by the Colonials. Again, spending cash - even with a war coming - doesn't say your bang per buck is any chop.)

Australia was making the largest cargo lift in the world in New Guinea - in German aircraft because Britain hadn't produced anything to do the job. Now, feel free to excuse that failure, but they still failed to produce an effective heavy cargo aircraft to match the Junkers types. Why is open for debate.

But Erik says "investment in, output out." and broadly the products, while different will be about the same worldwide. How fascinating, and how contrary to the evidence provided by the aircraft themselves, above (Junkers) and below. And so we come to Jacob's remarks:

"...cannot explain such facts as the UK’s development of technologies such as radar and the jet engine;"

Radar - (and much else) was a great achievement. But the jet is an interesting proof of British failure to bring technological progress to timely success. It has been argued that the British could have had jet fighters in 1940; perhaps a stretch, but von Ohan's first jet had flown long before and the jet-powered He 178 flew in '39. Thankfully the Germans thought they didn't need jet aircraft, otherwise... What was the main problem with getting British jets developed and into action? Appalling management, appallingly poor funding, and nearly driving the inventor of the jet insane after giving it to manufacturers who screwed up production. Then they put them in pretty average aircraft designs. The Me 262 is over-rated, but the Meatbox and Vampire were significantly poorer performers.

Again, why did Whittle take so long to succeed? The short answer is because despite all the claims for huge cash, R&D and so forth above, he was cash-staved and wound in red tape. The only wonder for Britain's jets is that Whittle didn't give up.

Britain's jet was not '...pioneered before the war.' either, but brought to fruition during it. It was a success. It was a close run thing only due to massive development and management incompetence. They didn't need enemy interference with the 'help' of Britain's technical and military establishment.

"The UK probably spent more than any other nation in the world on defence in the interwar period, and its aviation industry was the largest exporter of military aircraft in the world. Clearly someone thought its products were worth buying."

Well, the Commonwealth and Empire weren't allowed to buy anyone else's or produce their own - read that clown CG Grey's canards about CAC in Australia building American designed Wirraways - the irony being that Britain soon after had to buy off-the-shelf US equivalent Harvards because their own industry had failed to produce a design that could be built in enough numbers to train the RAF.

Jacob turns to production: "almost all of the productivity difference between the US and UK aircraft industry (at least during the war) was due to the larger US production runs. On the other hand, the US attempts to use pure mass production techniques were generally failures; the nature of production was such that runs were not long enough to gain the benefits (unlike for tanks and trucks.)"

Interesting. Firstly look at Ford's Willow Run and the fact that the most produced aircraft of W.W.II in the westen allies was a complex four engine bomber, that the Americans could supply to themselves, the British, and Australians by war's end. Then, perhaps look at the messy set ups of factories to produce aircraft by Lord Nuffield of Morris; the hiccups getting Spitfires into mass - rather than handbuilt - production. I'm not sure what criteria of success you are using, but the British factories were often slow and inefficient, badly managed and often needed government intervention to get going in W.W.II. (Note that this great exporter of military aircraft couldn't fulfill overseas orders to defend Dominions in the late 1930s and early forties.) Conversely the US went from being a minor exporter of military aircraft at the end of the thirties to the western world's arsenal in '45. It's some distorting mirror to avoid some conclusions there.

I like Chris' open arguments. I'd say that a fault of museums is they fudge poor performance, which may excuse some of the misunderstanding of actual technological data here. People operating the aircraft, albeit in non-original ways, have to understand stressed skin construction and smart and dumb ways of doing things, or it may well kill them. (Which is why I was keen to try and ensure Brett got to the Shuttleworth Collection this year.) It seems evident that an intelligent historian has a lot to learn in a restorers hangar, and while the interpretations there (and afterwards) may be up for debate, the actual data will be correct.