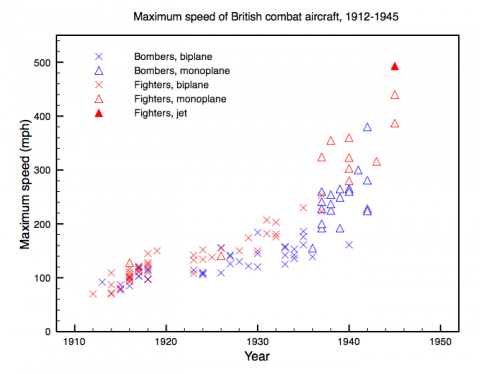

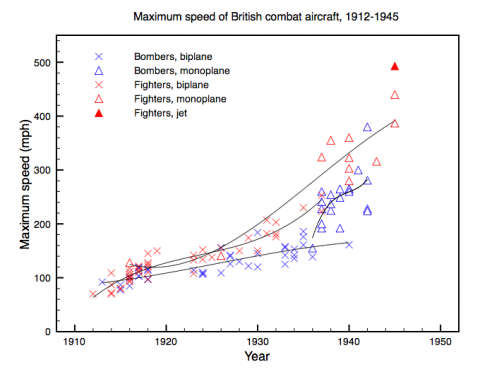

As promised, here's a revamped version of the speed plot I did the other day, this time distinguishing between biplanes (and triplanes), monoplanes and jets (just the one -- the Meteor). It's now a bit harder to read, though -- it's still red for fighters and blue for bombers, but now biplanes are represented by crosses (of the appropriate colour), monoplanes by open triangles, and jets by filled triangles. Also I noticed that my criteria for inclusion in the dataset had changed part-way through, so I've added a few aircraft to make that consistent (mainly torpedo-bombers) -- I'll update the original post shortly.

This shows very clearly the big jump that came with the move to monoplanes in the mid-1930s. And not just in fighters -- bomber speeds increased by around 100 mph. In fact, the last British biplane fighters, introduced in 1937, could barely keep up with their own bombers. Again, cubic spline fits to the various combinations illustrate this. (Referring to the left-hand endpoint of each fit, they correspond to biplane fighters, biplane bombers, monoplane fighters and monoplane bombers.)

Looking at the data again, there is another feature worth remarking upon. Based solely on the number of models entering production (ie, and not on the actual numbers of aircraft that were built), the period up to about 1925 is dominated by fighters, while the period from then up to the start of the Second World War is dominated by bombers. For the 1914-8 period, I think this is explained by the constant battle for air superiority over the Western Front, which saw new fighters rushed into service every few months to counter new German types. But I'm somewhat surprised that there were so many fighter types introduced in the early-to-mid 1920s, given that the bomber orthodoxy was supposedly being established at this time (though some of the fighters were for export or were otherwise speculative ventures, not designed to Air Ministry specifications). For the bombers, the reason would probably be the desire for a heavy bomber as a deterrent, but more so the increasing need for specialised aircraft adapted for different roles, as opposed to the "general purpose" aircraft common in the 1920s.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Chris Williams

The best way for the Air Ministry to keep design teams together while the Ten Year Rule was working its way through the system was to procure a squadron here, a squadron there, etc, from different manufacturers within the Ring. And it's cheaper to procure a squadron of fighters than one of bombers, so. . . QED.

For most of the 1920s, the giant stack of leftover Bristol Fighters and slightly re-engineered DH8s could after all do all the actual necessary bombing of lesser breeds.

Brett Holman

Post authorAh, good point -- I should have thought of that. I'm sure you're right. I suspect that it was for much the same reason that the Home Defence Air Force had slightly more fighter squadrons than bomber squadrons, even though the idea was to have 2 bomber squadrons for each fighter squadron.

Pingback:

Airminded · The widening margin