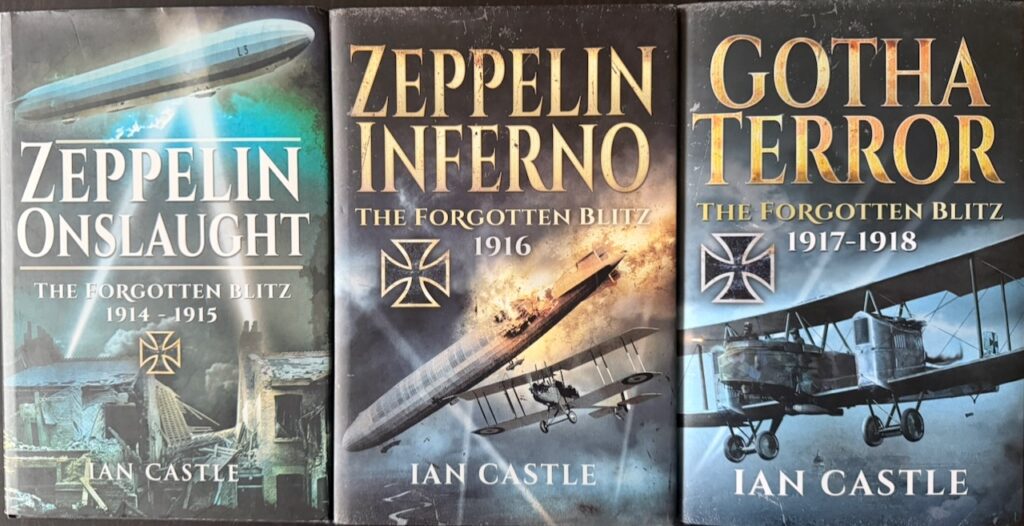

Ian Castle’s Forgotten Blitz trilogy

Somehow I managed to miss – by exactly a year! – the publication of the third and final volume of Ian Castle’s history of the Zeppelin and Gotha raids: I included Zeppelin Onslaught on my 1914–1918 air raids reading list back in 2022. In the meantime I’ve read Zeppelin Inferno, and having just finished Gotha […]