Sunday, 1 September 1940

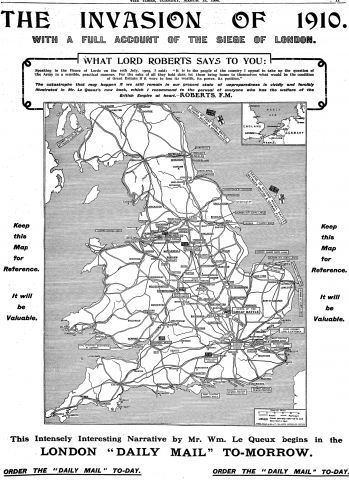

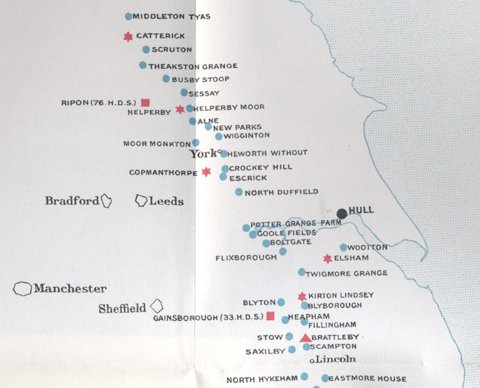

The New Statesman was a little off in its belief that the Germans have given up ‘blitzkrieg’ tactics, as yesterday they renewed their heavy daylight assaults against RAF aerodromes. According to the Observer (above, 7) they also targeted ‘women shoppers’ in two places near or in London. On page 8, there’s a handy map to […]