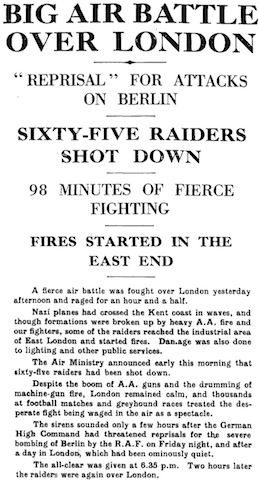

The New Statesman was a little off in its belief that the Germans have given up ‘blitzkrieg’ tactics, as yesterday they renewed their heavy daylight assaults against RAF aerodromes. According to the Observer (above, 7) they also targeted ‘women shoppers’ in two places near or in London.

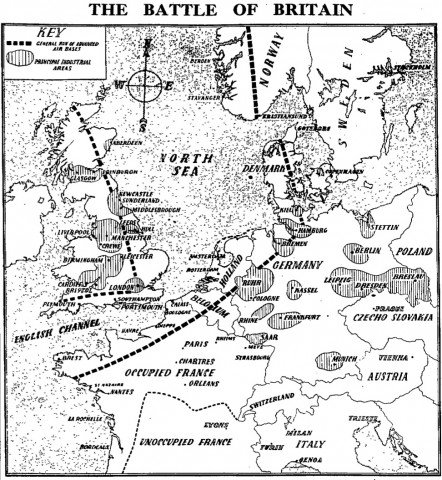

On page 8, there’s a handy map to help readers keep track of the strategy of the ‘Battle of Britain’ — the hatched areas are the ‘principal industrial areas’ in each country.

Germany is now known to have moved a large part of her air force to advanced bases in occupied territory in order to reduce the range for her onslaught on Great Britain. The general run of these advance bases is shown by the heavy dotted line.

The essential fact emerging from this map is that although Germany has an advantage for attacking our coasts and shipping by using bases in occupied territory our command of the sea places the Royal Air Force in a favourable position for striking at her industrial centres.

Here, the Battle of Britain seems to encompass not just Britain but Germany too, not just the attacks made on Britain but the attacks made by Britain. It’s interesting to note that the assumption that Britain rules the waves — itself somewhat questionable — leads to a further assumption that this somehow is a big advantage in bombing Germany. Why is unclear.

Every week the Observer has a column called ‘The people and the air raids’ (10), These ‘stories of calmness and resource’ are very much in the ‘We can take it’ vein.

The sirens continue to sound, the raids become longer — six and seven hours at a stretch — and the spirits of the people remain entirely undamped.

Here are a few examples:

Extract from letter written by a London woman aged ninety, after the recent air attack on Croydon: “Last evening’s raid did us no harm — in fact, Hitler would be shocked to learn that, au contraire, it caused us personally much entertainment … The villains will probably be around again to-night, as they want to get the aerodrome. Their attempt has helped our Fighter Fund, which is something that arch-fiend did not expect.”

Woman in North London at height of raid: “I liked last night’s searchlights better. These patterns aren’t so good.”

A woman crawling out of a shelter found her house had toppled down around her. Asked whether she had been frightened, she replied, smilingly: “It’s all in the game.”

There has been surprisingly little keeping-calm-and-carrying-on like this in the rest of the press so far — at least the parts I’ve read — but that may change.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Interesting snippets Brett.

I’m especially struck by the comment ‘our command of the sea.’ As you note it was hardly relevant to the bombing effort of either power, but I’d say it was fair enough as statement of reality. Obviously not total command, right up to the enemy’s shores with impunity etc. However, the RN continued to exercise broad command of home waters, including the Channel, especially at night; even penetrating and raiding into the French and Belgian ports on occasion. Excepting for its U-boat arm the Kriegsmarine was more or less constrained to cautious coast hugging. (Incidentally, are you really of the view that the writer meant that ‘Britain rules the rules?’)

This is the bit that puzzles me. To what extent did the writer – or anybody else in the country at the time – actually believe that a German invasion was a possibility? Without German command of the sea it was always an impossibility. Not an improbability, not a hazardous gamble, but an outright impossibility. Anybody who could believe in British command of the sea and the possibility of a German invasion would have been believing in obverse and reverse at the same time. I can broadly understand how the great Battle of Britain myth (that it forestalled inevitable invasion) has grown up since 1940, though in some ways I find it harder and still harder to comprehend its continued survival, but I just wonder – did people actually believe it then? So much of the hindsight has been done by people who have swallowed the myth wholesale that I fear that we cannot understand what people thought at the time, as we superimpose too much of our faith in the myth on them.

Thanks for catching that, spellcheck doesn’t help with the silliest mistakes!

I agree that Britain had at least dominance of the seas; but when you think of Norway and Dunkirk, yes the strength of the RN was crucial but they were still very close-run things. Nothing similar happened in the First World War, despite the much greater strength of the German navy, and the big difference you’d have to say was airpower.

Working out what people thought and believed is always tricky, but I think you’re unduly pessimistic about our chances of knowing the extent of the invasion fear in 1940. The Home Intelligence reports I discussed in a previous post have a lot to say about this topic, it crops up a lot in memoirs and letters, and it was still a concern of opinion-formers (e.g. politicians, editors) until the end of September. I’ve also argued that the invasion threat is bundled up in the phrase ‘the Blitz’, but as you note myths have a way of superseding history and this has been forgotten. There’s probably an article in that…

As regards the true extent of the invasion fear I hope you’re right and it can be unearthed. But at this point letters and other contemporary evidence are clearly valid, memoirs less so. There is also the issue of the ‘official invasion scare,’ by which I mean the belief that fear of invasion was whipped up by the government as a means of promoting national cohesion. Repairing morale and promoting unity was Churchill’s primary task and the one, above all others, that he showed a gift for.

Which leads us to ‘1940 as a watershed year in British history,’ a huge subject in itself.

Turning to the military realities I cannot agree that airpower can be seen to be decisive. Very important certainly, but not decisive in the sense that it could possibly have neutralised the RN’s superiority over the Kriegsmarine in any conceivable circumstances. The total obliteration of Fighter Command just doesn’t come into it.

Both the Norwegian campaign and Dunkirk provide ample evidence.

Norway was a strategic victory for Germany but a tactical defeat for the Kriegsmarine. It also, as well as pointing up the RN’s weaknesses in AA capability (something widely and repeatedly noticed) pointed up the Luftwaffe’s weaknesses in anti-shipping capability (something widely and repeatedly ignored). The RN’s losses to the Luftwaffe were relatively light, given all the circumstances and the almost total absence of allied air cover. The scale of the initial invasion was small compared with what would have been required to establish a beachead in England, but had the RN been able to intercept it at sea it would have been massacred. In the end, the allies only withdrew from Norway because of their setbacks in France.

At Dunkirk the weather helped the British. Every other circumstance was highly unfavourable. For a navy, it was just about the most hazardous – nay suicidal – conceivable operation. Brilliance of organisation, stalwart leadership, immense courage and determination etc, yes certainly; but ultimately lifting a third of a million men off was down to German failure, including the failure of Luftwaffe.

And as to Dunkirk, I’m put in mind of Holmes’s ‘curious incident of the dog in the night-time.’ What did the Kriegsmarine do to disrupt the evacuation? A flotilla of destroyers, boldly handled and prepared to sell themselves dearly (like Warburton-Lee at the first battle of Narvik) could have smashed the whole operation.

Any invasion fleet, however great the air superiority it enjoyed, would have been trying to carry out an operation that had more in common with Dunkirk than the Norwegian invasion (some of the poor German squaddies were expected to be in their barges for seventy-two hours, even if everything went like clock-work), while being subjected to attacks (in the night as well as the day) which would have been reminiscent of Warburton-Lee’s. It just doesn’t bear thinking about.

For the invasion to succeed command of the air was essential, but so was command of the sea. And command of the sea would not have been conferred by mere possession of command of the air. Denial of that simple truth is the core of the Battle of Britain myth.

Accepting that there was genuine fear of invasion in 1940, I suspect the role of mass psychology. Obviously most people did not fully understand the military realities (as I’ve tried to outline them above). But while the fall of France was obviously of critical strategic importance, it was also a shattering blow to British morale. At the time it might have been easy to convince oneself that Hitler’s master race droolings were actually valid.

Sorry, I think we’re talking at cross purposes here! I wasn’t connecting the issues of command of the sea and fear of invasion, though I can see why you might think so.

Firstly, I do agree that the RN’s superiority made a successful invasion in 1940 next to impossible, even if Fighter Command had been defeated. Maybe an invasion force could have been lodged ashore but if British morale didn’t simply collapse at this point (and there’s little evidence to suggest that this was likely) then they would have been cut off from supply by sea and eventually rounded up and captured. A mini-Stalingrad in Kent.

My comments about Dunkirk and Norway were not meant to suggest that airpower was ‘decisive’ over seapower. But at Dunkirk, as you say, the German navy did little; and yet the RN lost 6 destroyers (and the French lost 3). Without airpower, the naval side of an evacuation so close to Britain would not have been so hairy. In the Norwegian campaign, the German navy did come out, as this was essential to the operational plan. Yes, it took severe losses — partly thanks to extraordinarily brave but desperate acts like that of HMS Glowworm — but the far stronger RN should have been able to womp all over it. The RN even lost an aircraft carrier to German surface fire. Where were the battleships? Off in Scapa Flow hiding from German airpower and subs (or preserving a fleet-in-being, to put it more kindly). So I’m just suggesting that German airpower prevented the full force of British seapower from being used, not that it decisively trumped it.

Secondly, I’m not sure why you seem sceptical of the idea that people did think that Germany was going to invade in 1940. Yes, as I said above it was not going to invade, or was not going to invade successfully. And yes, this is part of the 1940 myth today (for a previous discussion, see here). But to argue that therefore people at the time weren’t, or even shouldn’t have been, worried about the possibility is to project backwards what we know now. Fear does not depend upon reality; indeed it thrives on rumour and ignorance. And surprise (why do I expect the Spanish Inquisition at this point?) — the fear of parachutists in May-June is a prime example of this. Perhaps people should have been more confident of the strength of the RN; but then they’d been confident of the strength of the French army too…

Though I should also add that expectation of a German invasion did not always mean fear of a German invasion; Home Intelligence reports indicate that some people hoped for an invasion, because it would be defeated and would shorted the war. Tis complicated.

Thanks for coming back on this Brett. And thanks for steering me to your earlier debate – I’ll read it when I’ve got time. I agree that, broadly speaking, we are approaching the issues from slightly different angles.

My point about Dunkirk is that given the nature of the operation (stopped or slow, inshore etc) nine destroyers wasn’t much of a bag for the Luftwaffe to boast of.

As for the loss of the Glorious, it is simply not true to say that the capital ships were holed up in Scapa. The Home Fleet was ordered to be ready to intervene in the Channel, while at the same time covering the Narvik evacuation. As it was, at least three of its four big ships were at sea, and (in the broadest sense) in the Norwegian theatre when the Glorious was sunk. While fear of air attack did constrain their movements, it was not the reason for the Glorious being left without heavy escort. That was just a botched episode in a largely botched campaign.

The Luftwaffe certainly prevented the full force of British naval superiority from being deployed, but once the Germans were established ashore in Norway dislodging them was always going to take far more resources (land, sea and air) than preventing them landing in the first place would have done. Had opportunity arisen, that could have been done by sea power alone. Air power would scarcely have got a look in.

Am I a little obsessed with doubting the fear of invasion in 1940? Possibly. But to me it is the other side to your perfectly reasonable point: ‘to argue that therefore people at the time weren’t, or even shouldn’t have been, worried about the possibility is to project backwards what we know now.’ There has been so much arrant tosh (I certainly exclude present company from this blanket complaint!) written and said about the military significance of the Battle of Britain that it has become a sort of mass brain-washing exercise.

Your last paragraph is something I’d never read before. Very interesting.

Clearly I do write some arrant tosh from time to time! I’ll just say one more thing: no, nine destroyers was not a lot in the scheme of things and certainly a price well worth paying. But to me the fact that it had to be paid at all is the significant point; it would have been a much cheaper operation for the RN in WWI.

Now, if it’s arrant tosh you want . . .

This isn’t relevant, but it is too good to leave unshared. From The Lost Gardens of Heligan, by Tim Smit (note that from the context of the passage there can be no doubt that the author is referring to WWI):

‘At the start of the Great War, the Royal Navy’s ageing fleet was mostly of timber construction and the Admiralty appealed for donations of oak.’

As regards a ‘WWI Dunkirk,’ it would have been far worse for the British if (and it’s a very big IF indeed) a sufficient proportion of the High Seas Fleet had been used to disrupt it. Had effectively been expended in order to secure a strategic victory.

Through WWI and WWII German surface warships were generally used very timidly compared with their RN counterparts. RN officers, especially in the smaller ships, tended to see ships as expendable weapons rather than assets to be preserved.

Which, of course, brings me back (sorry, I really must try to stop boring on about it) to the supposed invasion threat. A weaker navy, boldly handled, would have smashed it. The RN would have made mincemeat of it. Then ground it up again.

I can only hope you weren’t reading that book for the naval history, Neil! Speaking of which, you might find this to your taste.

Yes, I agree it would have been ‘interesting’ had the German Navy taken such a chance in WWI (intercepting the BEF as it crossed the Channel would be another such possibility). The difference in attitudes towards preserving ships is interesting, but in terms of the endgame of a war political considerations might come into play. For example to demonstrate the relevance of the navy after the war, especially if it looked like it was going to be won by the army. I could see Tirpitz sending his beloved fleet off into the RN’s maw if it got him more dreadnoughts after victory.

Thanks for steering me to to the Cumming book Brett. Yet another to add to my ‘to read’ list.

‘What, will the line stretch out to the crack of doom?’ (Acknowledgements to W Shakespeare, my research assistant.)

There are several books that deal with the broad realities of Sealion. Of those that I have read, the one that impressed me most was the earliest; Silent Victory, by Duncan Grinnell-Milne. Grinnell-Milne was an RFC and RAF veteran, who was apparently ostracised by some of his erstwhile comrades for his pains.

His sub-text seemed to me that Sealion was got up by Raeder, almost as means of educating Hitler and his satraps in the role of navies and the strategic realities of north-west Europe. So once preparations were going forward he had to pour as much cold water on it as he could without losing his role in the Nazi hierarchy. Rather, he had to guide Hitler into finding out for himself that the project was undeliverable without years of serious preparation.

I don’t know if that really was the case, but it seems highly plausible.

One of the problems with the British obsession with the Battle of Britain is that it encourages us to look at Sealion from the viewpoint of the besieged. Thus; Sealion didn’t happen, so we prevented it from happening. In reality it was the besiegers who would have actually had to launch the invasion attempt, and it makes more historical sense to look for their reasons for not trying it. And in 1940 even Hitler would have had to consult his admirals, who would have assuredly answered something along the lines of: ‘Are you stark staring barking, Mein infallible Fuhrer?

It’s really impossible to know what Tirpitz might have done, but don’t forget he resigned before Jutland. I rather think it was Wilhelm II, rather than Tirpitz, who was really into toy ships. The distinction I would make in attitudes to conserving warships (not submarines) would be between the RN, IJN and USN on the one hand and the German and Italians on the other.

Yeah, I was thinking of an early-war Dunkirk scenario there (after the German victory at the Marne, of course). My impression is that Tirpitz wanted as big a navy as possible, seeing it as coextensive with German greatness, and so might have been prepared to sacrifice his fleet to ensure its importance was recognised after the war. A quick victory won entirely on land would have done him no favours. Of course, as you say, we can never know.

Pingback: War Grave Photograph request for Oxford (Rose Hill) Cemetery - World War 2 Talk