The talk at Earth Sciences went well, I think. It was a good-sized audience and they seemed interested in what I had to say, judging by the questions afterwards. I also found out that one of the honorary fellows had actually lived in London during the war, and though only a child could remember watching out for V1s passing overhead and even the 'electric' atmosphere of the day that war was declared.

I was all set to record the talk, but forgot to fire up the audio app. At some point, I may try recording it again at home or just putting the text up. Until then, here are a couple of the graphs I used, along with some different ways of presenting the same numbers. (Except where indicated, the data is courtesy of Dan Todman, who compiled it from Home Office files. Thanks Dan!)

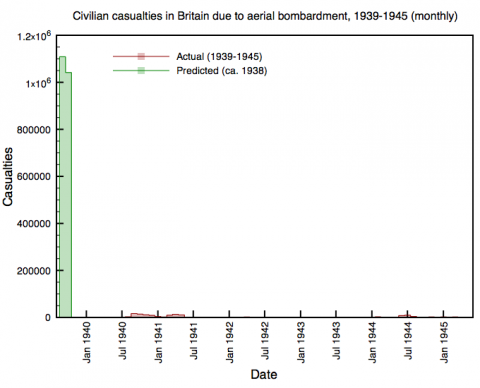

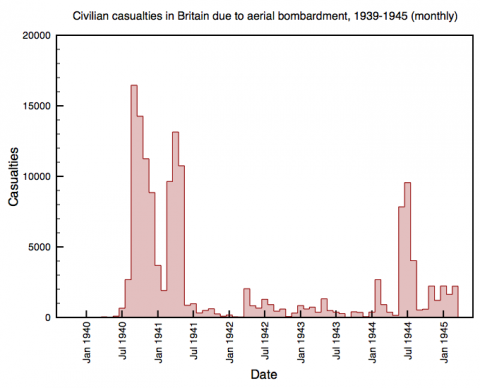

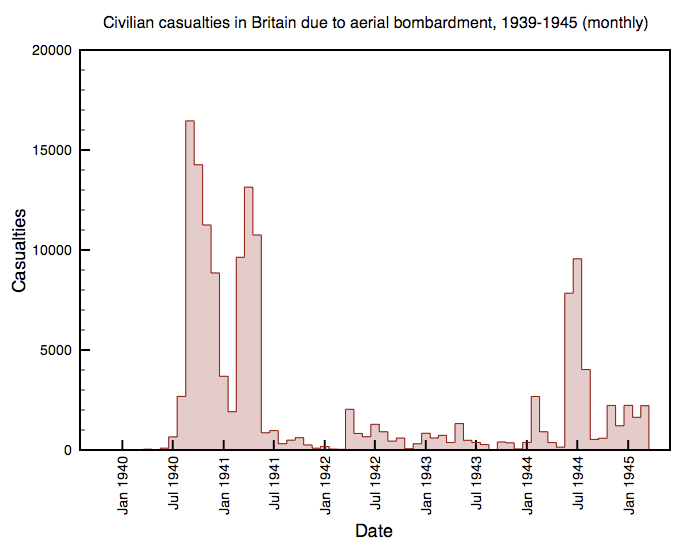

Firstly, this shows the civilian casualties (killed and seriously wounded) each month in Britain due to enemy action between 1939-1945. Most -- all? -- of these will have the result of bombing, so I've labeled it accordingly. (This is the counterpart of a histogram I did for 1914-1918, except that combined civilian and military casualties, and separated different forms of attack.) It's easy to pick out the Luftwaffe's major offensives: the biggest peak is September 1940, when the Blitz started; it ended in May 1941, after which casualties were never so high again. There's a relative lull in January and February 1941, due largely to bad weather conditions. In April-June 1942, there's the Baedeker Blitz and from January 1944, the Baby Blitz. Then there's the V-1 offensive in June-September 1944 and the V-2 offensive in September 1944-March 1945.

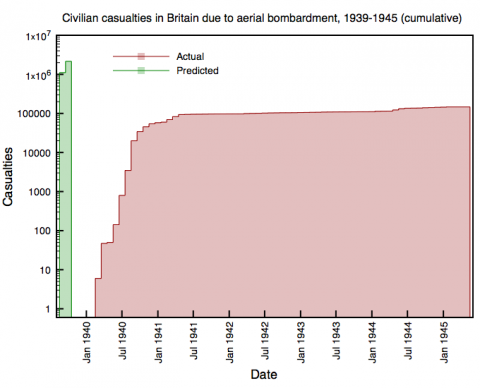

I thought it might be instructive to compare what actually happened with what was predicted would happen: if the knock-out blow had attempted and if pre-war estimates of German airpower had been correct. I derived this from figures provided by Richard M. Titmuss, Problems of Social Policy (London: H.M.S.O., 1950), 9 and 12-3 10, 13-4, which were estimates made circa 1938 by government bodies for a war starting in 1939. These lead to the following assumptions:

- the Luftwaffe could deliver 3500 tons of bombs on London in the first 24 hours of an attack, and an average of 700 tons per day for some weeks thereafter (Committee of Imperial Defence)

- the casualties caused per ton of bombs dropped would be 48 (24 killed, 24 seriously wounded) (ARP Department, Home Office)

- the war would last for 60 days (CID)

It's then simple to calculate that a German knock-out blow launched on 3 September 1939 would have led to a bit over 1.1 million casualties in September and a bit over a million in October, 168000 on the first day of war. More than a two million fatalities casualties in just two months.

It's easy to quibble with these assumptions -- for example, I'm using the most pessimistic multiplier for casualties, but that's partly because it's easy to relate it to the definition of casualties I'm already using. And my assumption that the 700 tons per day could be kept up for 60 days may well be too high, but I can't find anything better. The CID did estimate in 1937 that an aerial war of this length would kill 600,000 and wound 1.2 million, so that shows that I'm in the right range and also that officials did make these sorts of calculations at the time.

Anyway, the point of the histogram is to show that the actual bombing, as bad as it was, was nothing like as terrible as 'the expected holocaust' (as Tom Harrison termed it), and I think it succeeds -- you can just make out the Blitz and the V-1 attacks, but they're just tiny blips. However, precisely because of the huge disparity in scale, it's hard to make a meaningful comparison.

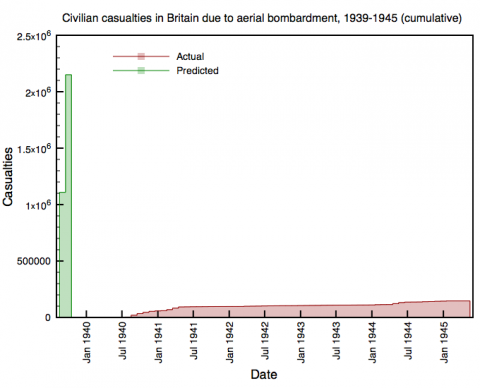

In his graphs of all British casualties, Dan opted for running cumulative figures rather than monthly ones, and that is indeed better for showing the overall picture -- whereas monthly is better at showing intensity, I think. So, here's my actual vs. predicted plot redone in cumulative fashion. Even by the end of five and a half years of total war, the scale of the knock-out blow isn't even approached. (In fact, I think that even when military casualties are taken into account, the knock-out blow still wins handily.)

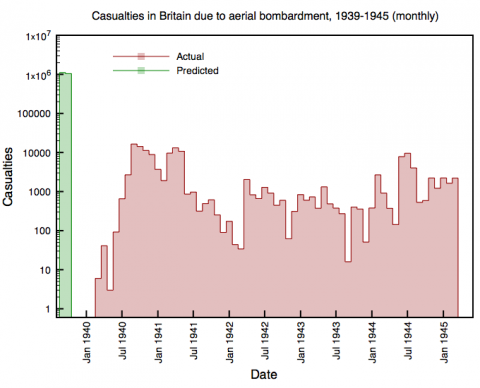

Here's a different way to present the monthly data. This time I've plotted the casualties on a log scale. This is good for showing changes in the order of magnitude, and it's immediately apparent that the knock-out blow was around two orders of magnitude (i.e., about 100 times) more intense than the worst month of the Blitz.

Finally, the cumulative casualty figures on a log scale. So, overall, the civilian experience of bombing over the whole of the Second World War (mainly meaning the Blitz) was about one order of magnitude (i.e. about 10 times) less devastating than the knock-out blow predicted shortly before the war.

The knock-out blow would have been 100 times more intense and 10 times more devastating than the Blitz was -- I'll have to remember that!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Dan

Nice graphs Brett! Particularly like the log scale - must learn to do that one.

The only thing I'd add is that I guess the point of the knock out blow is that it comes at once - whereas one of the characteristics of the bombing of the UK in summer 1940 was its development over time. Indeed, I think that's why the chronology of 1940, which we discussed in one of your earlier posts on parashots, is so important. Calder argues in The Myth of the Blitz, following wartime Home Intelligence reports (and Harrison's comments at the time), that the experience of aerial attack during the Battle of Britain - widespread but not as concentrated as the Blitz from September on - acted as a sort of inoculation to the horrors of air war on the Home Front. Bombing, it turned out, wasn't that bad - or so the Myth went - and this formed expectations about behaviour. So is it the worst month of the Blitz, or its first months, that we should be comparing to the knock out blow?

Gavin

A round of applause for using the phrase "order of magnitude" to mean what it actually does mean. I get really annoyed when historians use it as a vague metaphor without really understanding the maths.

roGER

Nice work - although I hate logerithmic scales - so decieving to the glance of an eye (and a lot of people, myself included do just tend to glance at a graph and just move on.

Brett Holman

Post authorDan:

I think that's a good point. I've thought for a while that dividing the air war into "the Battle of Britain" and "the Blitz" is unhelpful in some ways and this is another example of that. The top graph in this post (rather, the data you compiled!) shows that August 1940 was the period of heaviest casualties outside of the Blitz proper and the V-1 attacks, and about equal to the Baby Blitz. But it's all but forgotten next to to 7 September and after.

It comes through very clearly from Harrisson's Living Through the Blitz that the Luftwaffe's attacks on cities were most damaging and disruptive when the target hadn't been attacked before. Local government, ARP, emergency services and utilities all learned how to cope better after being bombed a few times (and, it seems, didn't learn much from the lessons of other cities -- or maybe there's just no substitute for experience). The same would likely be true of civilians in general. Much of the fear of air attack was in the not knowing what to expect. Once people did know, even if it was bad, it was a lot easier to bear.

And the suddenness of the knock-out blow is indeed key, as well as the fact that it comes at the start of war. I'm not entirely convinced that a knock-out blow couldn't have worked in September 1939, or at least been approached. A sudden, massive air attack at the start of war -- there wouldn't have been time to learn lessons or overcome anxieties. I doubt it would have knocked Britain out of the war but it could have been a lot uglier than the Blitz!

Of course, Germany didn't have the forces and it was more concerned to finish Poland off quickly. But that gave the British a year's grace to prepare.

Gavin:

Cheers! The legacy of a youth misspent in physics. I do know what you mean; another abuse of mathematics that always annoys me is 'infinitely': infinity isn't just a really, really big number ...

roGER:

Thanks -- though I wouldn't say that graphs themselves are deceiving (the person presenting them may be, if they don't label or explain them properly). Something I wanted to show with this post is that there's not any one best way to plot data: any method that you do choose will emphasise some aspect of the data at the expense of other aspects. It all depends on what story you are trying to tell. A bit like history itself, really ...

roGER

Yes, 'deceiving' probably wasn't the best choice of words...

Sorry!

Chris Williams

I'd refrain from using log scales on an audience that was comprised mainly of historians. Unless they were economic historians. Perhaps this is a comment on the numeracy of British historians!

Brett Holman

roGER:

Oh, I wasn't offended! And it was good chance to expand upon a point I wanted to make.

Chris:

Nah, it'd be good for them -- they might learn something!

Alan Allport

Dividing the air war into “the Battle of Britain” and “the Blitz” is unhelpful.

As Richard Overy suggests in his book on the Battle, this division encourages the popular but misleading belief that the London Blitz was a response to the RAF's attacks on Berlin. He argues that the framing of the Blitz as a retaliatory measure by the Germans was largely a rhetorical justification, and that the campaign had already been edging steadily in that direction throughout August.

Brett Holman

Thanks -- I must reread that book, if I ever have a spare 30 minutes!

Pingback:

Airminded · The widening margin

Pingback:

Airminded · Facing Armageddon

Pingback:

Airminded · The balloon goes up

Pingback:

The dragon will always get through — III | Airminded

Pingback:

1939 vs. 1940 – Airminded

Pingback:

Explainer: the terror behind Keep Calm And Carry On | Em News