This is the talk I gave at Earth Sciences back in May. It's long and picture heavy and much of it will be be familiar to regular readers, but some people expressed some interest in it so here it is. I've lightly edited it, mainly to correct typos in my written copy. I've put in links to the Boswell drawings because they're under copyright, and I've replaced one photo because I realised it was of British Army Aeroplane No. 1b, not British Army Aeroplane No. 1a! How embarrassing.

Facing Armageddon: Britain and the Bomber, 1908-1941

Today I'm going to give you an overview of my PhD thesis topic. My broad area is the history of military aviation in the early twentieth century, so first I'll give you a little background on that.

The first heavier-than-air manned flight was made by the Wright brothers in 1903, as you can see here. Within a few years, countries around the world started thinking about how they could use this new technology for warfare.

This is the British Army's first aeroplane, which wasn't very successful but did at least make the first ever flight in Britain. In 1914, the First World War broke out and this pushed aviation along very quickly. At first, aeroplanes were mostly used to find and report on the movements of enemy troops, but soon they were used to drop bombs on them too.

And when aircraft became powerful enough, they started to bomb targets far behind enemy lines. This is the German Gotha G.IV, which was used to bomb London in 1917 and 1918. Of course, each country also developed fast fighter aircraft to try to shoot down their opponents' slow bomber and reconnaissance aircraft.

Here's one of the most famous fighters of the First World War, the British Sopwith Camel, as flown by both Biggles and Snoopy. It was fast, agile, and armed with twin machine guns.

After the war ended in 1918, aviation technology continued to progress, though not quite as quickly. By the 1930s, air forces were starting to be equipped with sleek biplanes such as this Hawker Hart, which was the fastest aeroplane in the Royal Air Force -- which is a bit startling since it was actually a bomber and not a fighter!

The late 1930s witnessed the birth of a new generation of aircraft, powerful monoplanes with maximum speeds well in excess of 200 or even 300 miles per hour. They were also better armed than earlier aircraft: these Hawker Hurricane fighters had 8 machine guns.

This is one of the bombers that the Hurricane would be defending Britain against, the Ju 88, Germany's most effective bomber. It could carry up to 2.5 tons of bombs. Germany built over 14000 of these bombers by the end of 1945.

Finally, this is one of the most powerful bombers of the war, the British Avro Lancaster. It was capable of carrying up to 10 tons worth of high explosive or incendiary bombs to Berlin and beyond.

But that's all just by way of introduction. My research isn't actually about aeroplanes as such or how they were used. What I'm looking at is the fear of bombing in Britain in the early twentieth century, from the early days of flight before the First World War, up until the end of the Blitz on British cities in 1941. More specifically, I'm interested in how the threat of aerial bombardment of cities was debated in the public sphere, as distinct from what was being discussed behind closed doors by the government and the armed forces. A number of historians have written excellent studies of British air strategy and air policy. Many of them mention the pervasive fear of bombing on the part of the British public, especially in the 1930s, but nearly always, they just take this fear as a given, and don't spend much time trying to understand it or its origins. This annoyed me, because the little that they did tell me about the popular fear of bombing was fascinating, and I wanted to know more: why was the public scared of bombing, and what were they afraid would happen? Hence the thesis!

However, it's very difficult to measure public opinion itself, especially before the introduction of opinion polls (which means virtually all of the period I'm studying). You can get the occasional odd glimpse into what the average person really thought about the dangers of bombers coming over and blowing them up, but perhaps not enough to do a whole thesis on. So instead I'm focusing on some of the most important influences on public opinion: primarily books, journals and newspapers which discussed the air menace and what should be done about it. And to a lesser extent, I also use things like cinema newsreels, films and radio broadcasts. Concerned citizens -- often professionals such as military experts, doctors, or scientists -- used all of these forums to present predictions of what would happen to cities and civilians under air attack, along with their proposals about how to solve the problem. Novelists took the serious speculations of the experts and turned them into nightmarish visions of what future wars held in store for the inhabitants of great cities. These fictional scenarios in turn coloured much of the debate about bombing. In fact, fictional and non-fictional discussions about bombing were often remarkably similar to each other.

So, what was the threat? Most people today have probably heard of, for example, Guernica, the Blitz or Dresden, which are all still potent symbols of the horrors of total war. This is Guernica, a small town of about 5000 people in the Basque country in northern Spain. In April 1937, during the Spanish Civil War it was devastated by a German air raid.

London was bombed by the Luftwaffe on 57 consecutive nights from 7 September 1940, forcing more than 200,000 people to take shelter in the underground railway stations every night. Here are just some of them in Elephant and Castle.

And this photo was taken from a British aeroplane during the Allied air raids on the German city of Dresden in the middle of February 1945. The little points of light are incendiary bombs, which started a massive firestorm. About 30,000 people -- men, women and children -- were killed in these raids.

But as terrible as these events were -- and there are many more I could have mentioned -- they were nothing compared with the predictions made before the war. Essentially, the widespread belief in the 1920s and 1930s was that at the beginning of the next war, a huge fleet of enemy bombers would suddenly strike at London and other cities and destroy them with high explosive bombs, incendiaries, and poison gas, causing hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties within a matter of hours or days, shattering essential infrastructure and leading to mass panic. Under such circumstances, it was widely assumed that Britain's government would be forced to surrender within days or weeks of the outbreak of war. This is what was sometimes called the 'knock-out blow', that is, the sudden blow which would knock Britain out of the war.

This graph shows the effects of the German air raids on Britain in the First World War. 'Casualties' means the number of people killed or seriously wounded, in this case in each month. Green shows the casualties caused by airships, and red the casualties caused by aeroplanes. Note that it peaks at about 600 casualties in any one month.

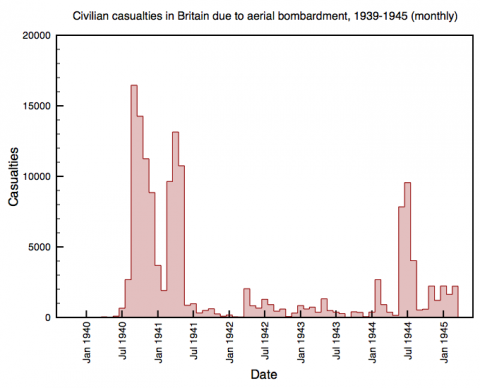

And this is the equivalent graph for the Second World War. The peak casualties per month has shot up to more than 16000. That's September 1940, when the Blitz began. In all, there were more than 146000 civilian casualties in Britain during the war, around a third of whom were killed.

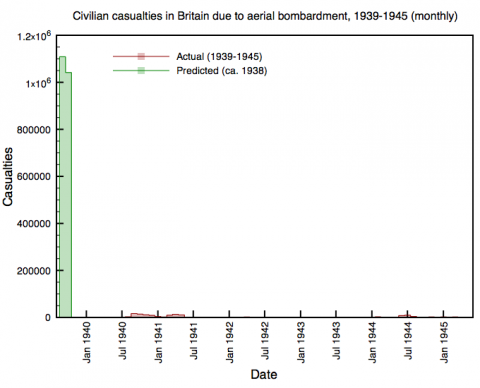

Now, here's a comparison between what actually happened in 1939-1945 and what British government officials in 1938 predicted might happen if a war started in 1939 -- that's the knock-out blow: over a million casualties per month, half of them fatalities, over only two months. Nearly two orders of magnitude more destructive than what actually happened. These estimates were not plucked out of thin air, but they weren't much more than naive extrapolations from the First World War experience: divde the number of casualties between 1914 and 1918 by the tonnage of bombs dropped, and then multiply by the number of bombers the enemy had and the amount of bombs they could carry. This turned out to be a huge exaggeration, but you can see why everyone was so worried!

In extreme versions of the knock-out blow, civilisation itself would collapse, as the complex webs of commerce, transport and social control which bind society together break apart, leaving people to fend for themselves as best they could. From the perspective of a later generation, this sounds a lot like the effects of nuclear war.

And in fact in 1966 Harold Macmillan, a former Conservative Prime Minister who had been a backbench MP in the 1930s, wrote that 'We thought of air warfare in 1938 rather as people think of nuclear warfare today'. It could in fact mean the end of life as we know it.

I'll now give you some typical examples of how this fear of the bomber was manifested in literature and the arts. The following quotes are from a knock-out blow novel published in 1934 called Invasion from the Air. Firstly, the enemy air force attacks suddenly, with little or no warning, just after or even before the declaration of war:

At five minutes to twelve on that fateful night Germany struck from the clouds. The blow was totally unexpected, for the declaration of war by Britain against Germany and Italy had no more than been conveyed to the departing Ambassadors [...] London's bewildered eight millions were precipitated into actual war conditions before the majority of them knew there was a war.

Secondly, the attack is massive in scale:

Squadron after squadron assailed the cities and towns in waves, each wave having its separate duty and aims. Upwards of two hundred enemy aircraft -- fighters, bombers and [poison gas] sprayers -- were brought down that morning as against only fifty British machines, but eight hundred broke though all attempts to stop them.

And thirdly, it is devastatingly destructive:

Thousands of people were killed or burnt to death or died subsequently insane at the memory of that battle, while, as always after the raids, vast numbers developed later the agonies of poisoned

lungs and throats, eyes and nasal passages [...] When the battle had passed Regent's Park was scarred with great pits where explosive bombs had fallen [...] the bodies of old and young, broken and mutilated, lay everywhere.

So the knock-out blow would bring the horrors of the trenches of the Great War into everyone's homes.

The Fall of London: Waterloo, by James Boswell (1933)

Next, here are some drawings which were actually commissioned for the novel I've just quoted from, but in the end weren't actually used. They show the aftermath of the attacks, as the terrified mob revolts and rampages through London. Wrecked trains at Waterloo Station.

The Fall of London: Corner House, by James Boswell (1933)

A patrolling soldier in gas gear tramping past the body of a woman.

The Fall of London: The Colosseum, by James Boswell (1933)

The rioting crowds, clashing with troops. An upper and middle-class fear of the unruly mob goes back at least to the time of the French revolution; more recently, since 1918 there had been an increase in working-class assertiveness and the example of the Russian Revolution to worry about. So the fear of the knock-out blow was not only about the possibility of war but also reflected other anxieties about British society.

Now, I'll show you a clip from the 1936 film Things To Come, which was adapted from a novel by HG Wells. This was a history of the future in three parts, and was a big-budget spectacular for its day. The first part of Things To Come features a graphic depiction of a gas attack on a city called Everytown, which bears a suspicious similarity to London. It was Wells' argument that the destruction of modern society by total warfare was a necessary prelude to its recreation into a technocratic, utopian world state.

So much for the threat of the knock-out blow. What could be done about it? Surprisingly, the obvious answer, the one that actually did work in the Battle of Britain -- air defence by fighter aircraft and anti-aircraft guns, harnessed to a sophisticated command and control system -- was given little credit. It was widely believed that bombers were too fast and too well-armed to be shot down, at least in sufficient numbers to stop an attack.

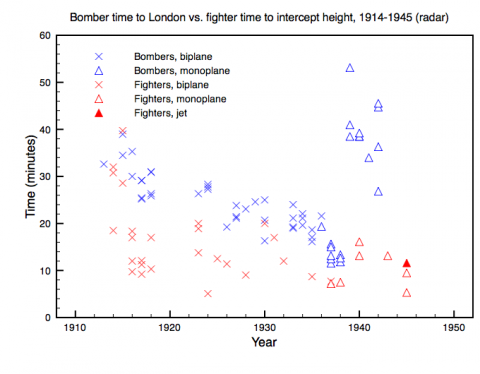

I'll show you a graph which helps explain this pessimism. First here's a map showing Britain in relation to Europe, and some of the directions from which enemy bombers might attack. Ideally, the defending fighters would intercept the bombers before they reached London, the biggest and most important city. But there weren't nearly enough fighters to keep up a standing patrol, so they'd have to wait until an air raid was detected, and then take off to intercept it. However incoming aircraft could usually only be detected once they'd crossed the coast. And it's only about 50 miles, give or take, from the coast to London. The problem was that as technology improved and bombers got faster, there was less and less time for the fighters to react.

This graph shows in blue the time in minutes it would take for a bomber to cross the 50 miles from the coast to London. In the First World War, this could take around half an hour. By the Second World War, this time was down to only 10 minutes or so. The points in red show the time taken for the defending fighters to take off and climb to the height of the attacking bombers. As you can see this time is generally less than the crossing time, so in theory the fighters would have time to find the bombers and hopefully shoot them down. But lots of things could go wrong -- the bombers might be detected late, the detection might not be reported soon enough, the bombers might have changed course or be hiding in cloud and so on. So the greater the margin of safety the better. In the 1930s, this margin was only 5 to 10 minutes which was not reassuring at all. Air defence exercises in the early 1930s seemed to confirm the difficulty of intercepting bombers before they could reach their target.

As the former and future prime minister Stanley Baldwin pessimistically told Parliament in 1932,

I think it is well also for the man in the street to realise that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed, whatever people may tell him. The bomber will always get through

A widely-quoted remark at the time and for years afterwards. He went on to offer the standard alternative: essentially to bomb the enemy harder than they bombed Britain.

The only defence is in offence, which means that you have got to kill more women and children more quickly than the enemy if you want to save yourselves. I mention that so that people may realise what is waiting for them when the next war comes.

One solution, then, was a bigger air force so that Britain could kill more women and children more quickly than any enemy.

This was a solution generally favoured by those on the political right, such as the Hands Off Britain Air Defence League. This is a leaflet they distributed in 1933 or 1934. As you can see, they ask 'Why wait for a bomber to leave Berlin at 4 o'clock and wipe out London at 8?'

Their demand is for the creation of 'a new winged army of long-range British bombers to smash the foreign hornets in their nests'. This was in fact the official Royal Air Force strategy at the time, pretty much, though due to years of disarmament and budget cuts, it did not have nearly enough aircraft to carry it out. The British governments of the 1930s did begin to rearm, but were reluctant to do so too quickly for fear of harming the economic recovery or offending the Germans.

There were also those, generally on the political left, who rejected the logic of two nations trading massive blows with each other, for it seemed likely that even the victor in such a war would be devastated. What alternatives were there? One was to mitigate the effects of bombing, by preparing Air Raid Precautions, or ARP as it was known. This could mean everything from training civilians in how to survive poison gas attacks, to the construction of deep shelters able to accommodate thousands of people during air raids. Although this sounds unobjectionable, some pacifists could and did argue that ARP was a mere palliative, and might actually invite war by making Britain feel over-confident about its ability to withstand a knock-out blow. So they favoured more radical solutions such as complete disarmament, or at least the abolition of military aircraft. But this in turn encountered problems. During the 1920s and early 1930s, the idea developed among aviation specialists that large civilian aircraft such as airliners could be easily turned into bombers, more or less by strapping bombs under the wings. This possibility undermined disarmament efforts because it was feared that once all nations had disbanded their air forces, an aggressor could arm its airliners and hold the rest of the civilised world to ransom. So, one proposed solution to this dilemma was to place the civil aviation industries of all countries under international control.

|

|

From there it was a logical step for many supporters of collective security to propose the formation of an international air force, a very popular position in the early 1930s for parts of the left and one which was under serious consideration at the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva in 1932. An international air force would harness the devastating power of the bomber to uphold collective security, because if one country attacked another it would immediately be bombed itself by the combined air forces of the world. It was also attractive to some people as a possible foundation of a world state, which would end war forever by ending nations themselves.

So, I've explained what people thought bombing would do, and what they thought could be done about it. I would lastly like to talk about the discourse itself, how these problems and solutions were propagated from specialists to the public. In the ordinary course of things, most people don't pay much attention to even existential threats such as terrorism, nuclear warfare, asteroid impacts, or indeed the knock-out blow. They may well be aware of them, and even anxious about them to some degree, but such information as they may pick up from the media, books or conversations with acquaintances will be random, fragmentary and possibly unpersuasive. It often takes some crisis, real or perceived, to concentrate people's minds on the supposed threat to society, and here the mass media plays a key role in creating the perception that there is a threat, and in suggesting solutions to the threat. So I suggest that this process is very much like the concept of a moral panic, as proposed by the sociologist Stanley Cohen in 1972. Usually this is a media-driven panic about the danger posed to society by some group within it -- like criminals, drug users, religious cults. But it seems to me that something closely analogous can happen in relation to external threats to society. To distinguish these incidents from moral panics, though, I call them defence panics. Defence panics seem almost endemic in Britain in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Initially these expressed fears about the loss of British naval supremacy and the possibility of invasion by a foreign power such as France or later Germany. The most famous expression of this was the great dreadnought panic of 1909, when an intense press campaign called for the laying down of 8 new battleships to pre-empt a supposed acceleration in the German naval construction programme. But only a couple of months later, there was a similar panic, this time time over German airships, and this panic was itself repeated on a larger scale in 1913. From then until the Second World War, the threat of air attack was unparalleled in its ability to create defence panics. Examples include scares over the size of European air forces in 1922 and 1935, claims about German preparations for biological warfare in 1934, the bombing of Spanish and Chinese cities in 1938 which were part of the background to the Munich crisis, itself a major defence panic, and finally the shocks of the Gotha air raids on London in 1917 and the Blitz in 1940.

In the end, the knock-out blow never took place, because the power of the bomber was greatly exaggerated. But the belief that it could happen itself shaped how the British prepared to fight the war that did come. The internationalist solutions such as disarmament or the international air force never worked, because few nations could even contemplate giving up their sovereignty like this. Britain did invest in trying to avoid the worst effects of a knock-out blow, with air raid shelters and plans to evacuate the cities. But their ARP schemes were never very comprehensive, and individuals did little to prepare for bombing on their own behalf until war came. Far more was spent on the armed forces, and most important here was air defence. Even though in the early 1930s nearly everyone was pessimistic about the fighter's chances against the bomber, effort was still put into improving them, resulting in fighters like the Hurricane which I showed earlier. These played a essential part in blunting the bomber offensive in 1940, at least in daylight. But another crucial technological component of the solution to the the problem of the bomber came, bizarrely, from almost pseudoscientific attempts to find an electromagnetic death ray. Death rays didn't help shoot down bombers, but radar did help find them.

A top-secret chain of radar stations around the coast was set up in 1939, just in time for the Second World War. This had an effective range of 120 miles. So instead of only being seen when they crossed the coast, bombers could now be detected far out to sea.

Returning to our graph showing how long it took for bombers to cross the 50 miles from the coast to London. With radar, this distance effectively increased to 170 miles.

I've factored that into this graph, and as you can see, from 1939 the defenders had a much greater warning time, 30 to 40 minutes. Radar tilted the balance greatly towards the defenders. No longer was it a certainty that the bomber would always get through.

So part of the answer to the problem of the bomber came from an unexpected quarter. But it didn't just arrive by accident, it only came because people were worried about the problem and were looking hard for a solution. Sometimes, muddling through and hoping for the best just isn't good enough, not when the survival of civilisation is at stake.

Image sources: Wikimedia Commons (Wright Flyer, Avro Lancaster); RAF (here and here); Gotha GIV; RAFA Costa Blanca; World-War-2-Planes.com; Guernica, specchio del Novecento; Caring on the Home Front; Wikipedia; Airminded (here, here and here); YouTube; Norman Macmillan, The Chosen Instrument (London: John Lane The Bodley Head, 1938), 21; eBay; David Davies, Suicide or Sanity? An Examination of the Proposals before the Geneva Disarmament Conference (London: Williams and Norgate, 1932); An International Air Force: Its Functions and Organisation (London: The New Commonwealth, 1934). I can't find where the photo of the Hurricanes came from; but it's almost certainly under Crown Copyright.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Radagast

Fascinating! All the best with the PhD!

Pingback:

Things noted « Mercurius Politicus

DCA

Great stuff: please finish soon, and get it published!

What about Wells' _The War in the Air_? As I remember, this also predicted the total destruction of civilization.

And (the statistician in me asks) was the ratio of casualties to tonnage of explosive higher in WWI than WWII? What about for bombers vs V-weapons?

Bob Meade

Looks good. Potential for a book in this too, I think you need a UK publisher.

CK

Brett, sterling work, bur you should surely find a place for the magnificent Vulcan Bomber.

Potential deaths in the millions something of a shame, of course, and somewhat outside the thesis. But hey, lovely clip:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wSNxC4PfaY&feature=related

Ricardo Reis

Last night I just realized something interesting. American bombing of Japan, with incendiary bombs, seems to be much more devasting than Europe. At least it looks like several Dresdens because of the wood/paper construction of japanese cities. And, at the same time, it is taken like a sideshow, the repercussions on the imaginary are some orders of magnitude lower than the London Blitz or Dresden. Obliterated by the A bomb?

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks all!

DCA:

Yes, The War in the Air is definitely an important part of this literature (and arguably The War of the Worlds anticipates it too, in some respects). It's partly why I start in 1908, too.

It's a good question about the stats -- in fact I think I'll work it deserves a post of its own. The short answer, though, is that the ratio of casualties per ton decreased between WWI and WWII, and the V-weapons had higher ratios than bombs.

Bob:

Would love to publish a book from it ... once it's submitted, I'll start looking for a publisher.

CK:

Sorry, I doubt any of the V-Force will make it in!

Ricardo:

Yes, you're right on all counts. Also, by the end, the air defences of Japan were so weak that the B-29s could discard their defensive armament and fly low, maximising their bombload.

CK

Thanks Brett. I do love this blog and good luck with the thesis (and I realise its European focus), but I would have thought that something should be mentioned about the bombing of Tokyo:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombing_of_Tokyo_in_World_War_II

...with a conservative estimate of 100,000 deaths in a single night.

Obviously by this stage of the war any concepts of morality were well out the window, and the Japanese war cabinet made Hitler's bunker look like a model of reasoned liberal debate, but it was THE apogee of strategic bombing in WW2.

Brett Holman

Post authorI make no apologies for not talking about Tokyo, since my topic is Britain and the bomber, not a general history of bombing! Even Dresden is outside my temporal range, but I mentioned that at least partly to show that I wasn't out to bag the whole German people (of whom there were a number in the audience!)

Ricardo Reis

No apologies needed :)

Pingback:

Shock and Awe No. 4 « culture

Pingback:

derivative » Blog Archive » Shock and Awe No. 4

Pingback:

The Sound Mirrors of Denge « Passing Strangeness

Nige Cook

Excellent post. I especially like the graph of the 1938-predicted million casualties from air raids at the outbreak of war to the actual result, practically zero!

I need this data for a blog post on the exaggeration of the effects of weapons for political purposes. Hope you don't mind if I borrow it and cite this post?

Nige Cook

Herman Kahn's 1959 testimony to the 22-26 June 1959 U.S. Congressional Hearings on the Biological and Environmental Effects of Nuclear War, page 833:

'Let me start by making some remarks about quantitative computations. The most important reason for being quantitative is because one may, in fact, be able to calculate what is happening. Many of the witnesses have emphasized the uncertainities of thermonuclear war but ... Napoleon ... would have been impressed with the relevance of quantitative calculations; impressed with the accuracy with which people predict what a nuclear war is like. ...

'This is of some real interest; before World War II, for example, many of the staffs engaged in estimating the effects of bombing over-estimated the effects of bombing by large amounts. This was one of the main reasons that at the Munich Conference and earlier occasions the British and the French chose appeasement to standing firm or fighting. Incidentally, these staff calculations were more lurid than the worst imaginations of fiction. [Air bombing was predicted to destroy whole cities in firestorms in a single air raid, with clouds of poison gas killing everyone for hundreds of miles downwind!]'

I've found that all the effects of nuclear weapons have been massively exaggerated, e.g. Philip J. Dolan's originally Secret - Restricted Data 1,651 pages long 'Capabilities of Nuclear Weapons' (linked in PDF on my post) gives an entirely different and more realistic evaluation of various effects like the ignition of fires (which is grossly exaggerated in the popular media) than his co-authored 1977 book with Glasstone, 'Effects of Nuclear Weapons'. It's a bit like the 1930s exaggeration of gas bombing and incendiary attack firestorm risks!

Brett Holman

Post authorSure, I CC all my posts so feel free to repost anything.

I didn't know that Kahn referred to the prewar bombing predictions. I wouldn't say the staff predictions were higher than the fictional ones, there were some novels which depicted a post-attack England as almost completely depopulated. I would also point out that until 1937-8 there wasn't any good evidence either way as to whether such predictions were exaggerated or not; pacifists and militarists used the same lurid scenarios to support their very different agendas.

Nige Cook

Thanks! The staff predictions relied on the assumption that the enemy would choose what Herman Kahn called a 'wargasm' (quote from Kahn's fellow RAND Corp strategist Thomas Shelling, in the 1992 BBC2 'Pandora's Box' series episode called 'To the Brink of Eternity'), where each side irrationally tries to use up all its weapons for killing innocent civilians as soon as it can. There is really no evidence for this kind of anti-civilian planning. The staff calculations clearly didn't affect the offensive plans for bombing by the RAF: if it did, why the Phoney War period? Why didn't the RAF go out straight away and bomb German cities in September 1939? Clearly the staff calculations did not constitute planning for offensive use at all! They had little interest in bombing civilians, except in retaliation.

Dolan's 'Capabilities of Nuclear Weapons', 1981, Part 2, Damage Criteria, Chapter 14, 'Damage to Military Field Equipment', p. 1 states:

‘One of the primary uses of nuclear weapons would be for the destruction of military field equipment.’ (Originally 'Secret- Restricted data'.)

Note that in 1963, Dolan compiled the famous U.S. Army Field Manual, 'Nuclear Weapons Employment', FM 101-31.

But this is not mentioned in his co-authored 'Effects of Nuclear Weapons 1977', which goes on endlessly about civilian effects and excludes all the evidence that nuclear weapons would be used against military targets. Only 30 pages out of 1,651 pages in the classified manual deal with personnel casualties. It was the same before WWII: calculations for political consumption made it look as if a war would involve horrendous civilian suffering, but the actual offensive planning was totally different.

Brett Holman

Post authorI don't agree with your analysis of RAF planning (I can't really speak to the nuclear stuff!) Why didn't Bomber Command immediately attempt a knock-out blow against Germany at the start of WWII? For a start it was still weak. It was not the powerful force it was to become in 1943-5. Starting a tit-for-tat city-bombing contest with the Luftwaffe (wrongly thought to be substantially stronger than the RAF) didn't seem like a clever thing to do. Also, a symmetric counteroffensive wasn't the only way to respond to the German aerial threat. For example, one plan which was formulated (but not given much weight) was a strike at German aerodromes and aircraft factories (WA1). In theory this would soon reduce the weight of bombs the Luftwaffe could drop on London to bearable levels. There's also the moral issue: before the war it was pretty much axiomatic that Britain would not initiate the bombing of civilians. I think you also ascribe too much consistency to the Air Staff. They certainly planned to undertake strategic bombing of some kind; yet they neglected to make training in long-distance navigation (for example) a priority during the 1920s and 1930s, which might have helped minimise the problems faced by RAF bomber crews early in the war. Finally, the RAF did target civilians during the war. Specifically German workers, but also the houses where they and their families lived. This was a strategy which evolved during the war, albeit from some prewar ideas.

In short, the RAF's bomber advocates had a genuine belief in the primacy of the bomber during the 1930s, but didn't think about it or test it in any rigorous manner.

Nige Cook

Hi Brett, thanks for your reply! Yes, by 1939 the RAF was not in a strong position compared to the feverish production of weapons by Germany and its acquired territories, so a tit-for-tat bombing contest was not on the cards because Britain had nothing to gain and plenty to lose from that course of action. I think perhaps you might agree that there was a moral issue existing in addition to the military fear that Britain didn't have enough power? E.g., consider Britain's stockpile of mustard gas, which it didn't use against Germany despite every person in Britain having a gas mask, which wasn't the case in Germany, which had a shortage of rubber.

At no point did Britain exploit this gas advantage; nor did it use anthrax which it tested and stockpiled. By the same token, Hitler never used nerve gas against Britain. This was partly because Britain would retaliate and partly because the general purpose activated charcoal absorbers in British gas masks were perfectly capable of absorbing nerve gas vapour, so Hitler would have had to use doses 3,700 times higher than the lethal inhalation concentration for tabun and 3,100 times that for for sarin, to kill by skin droplet absorption, assuming people were outdoors.

Tabun was discovered by Dr Gerhard Schrader in Germany on 23 December 1936. Germany made 12,000 tons as a war gas between April

1942 and May 1945, but did not use it for fear of heavy mustard gas reprisals. For comparison, Iraq made only 210 tons, using it at Basra

against the Iranians on 17 March 1984. Outside the lab, it gets dispersed and diluted so easily in the atmosphere that it takes immense quantities to have the intended effect.

So even if you don't want to get into the nuclear question, the chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction available during World War II simply weren't used. Regardless of the exact influence of moral versus military considerations in determining not to use weapons of mass destruction, it does indicate that even the most deplored dictator in history didn't try to use weapons of mass destruction against civilians during war. He instead used hydrogen cyanide gas (patented as 'Zyklon B'; Dr Brune Tesch discovered oxalic acid would convert could solidify hydrogen cyanide into solid crystals for convenience) to exterminate 6 million people, ethnic minorities and others.

I just think that there's a lesson here that is being missed due to mainstream groupthink: weapons of chemical and biological mass destruction were available to both sides during WWII, but weren't used in the conflict for various reasons. Fear of escalating the depravity of the conflict without getting any benefit, loss of moral prestige, a desire to wait for the other side to descend that low first, whatever. Weapons of mass destruction were however used in gas chambers for genicide. Anyone rational would conclude that the biggest threat is not from aerial bombardment but from non-military genicide in concentration camps. (Naturally, nobody with a large propaganda budget has any vested interest in pushing this extremely anti-pacifist fact into public debates.)

Chris Williams

Not if you were Japanese in 1945 it wasn't.

Nige Cook

Hi Chris, yes the Japanese did use biological warfare during World War II: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unit_731

"According to the 2002 International Symposium on the Crimes of Bacteriological Warfare, the number of people killed by the Imperial Japanese Army germ warfare and human experiments is around 580,000.[5] According to other sources, the use of biological weapons researched in Unit 731's bioweapons and chemical weapons programs resulted in possibly as many as 200,000 deaths of military personnel and civilians in China."

This was more Hitler's gas chamber genocide than hot blooded aerial bombardment; Japan never actually dropped biological warfare agents on America. Maybe you are also thinking about the incendiary air raid on Tokyo in March 1945, or even the propaganda-hyped nuclear explosions over Hiroshima and Nagasaki with their trivial effects (conventional weapons type injuries plus just 400 cancers linked to radiation - above the control group - spread over 50 years)? As with Hamburg and Dresden, these attacks occurred relatively late in the war, and had relatively little impact.

Japan surrendered conditionally after Nagasaki principally because Russia (which Japan had been hoping would help it negotiate a surrender) declared war on Japan, seeing that the war was coming to an end with nuclear warfare, and preferring to be included as a victor in the war against Japan than not. If Japan had not surrendered, the next nuclear attack wouldn't have come until September because of the bottlenecks in production of fissile material, and it's civil defence plans based on the observed effects of nuclear attack would have prevented mass fires due to overturning of charcoal braziers, the flash burns and the glass fragment injury from delayed blast arrival after the single bombers were spotted...

Chris Williams

"these attacks occurred relatively late in the war, and had relatively little impact."

I can't help thinking that the firebombing of Tokyo can only be said to have had 'relatively little impact' if there's something a bit off about your overall argument.

[As it happens, I share your heretical belief that the a-bomb wasn't actually much more destructive than Bomber Command at the top (?) of their form.]

Brett Holman

Post authorWhat Chris said (on both counts). Aerial bombardment was devastating; at least half a million civilians died from it in WWII, perhaps more than a million. It just wasn't devastating enough, consistently enough to cause a knock-out blow, as predicted by many before the war; and people didn't react to being bombed the way they were 'supposed' to. You're right, Nige, that both sides were deterred from using chemical weapons in WWII, but I'm not sure what your point is. You can't drop a gas chamber on an enemy city and hope that its citizens will walk into it for you, after all, so concentration and coventration aren't comparable.

Why Japan surrendered is still a contentious question. Recently the Soviet invasion of Manchuria has assumed greater importance in the historiography than previously, but the atomic bombs were still crucial. (In the words of one member of the peace faction in the Japanese war cabinet, Hiroshima was a 'gift from heaven'.) Yes, another atom bomb wouldn't have been ready for some time, but the Japanese decision-makers didn't know that. I'd be interested to know where you get your information about Japanese civil defence capabilities against atomic attack, as they didn't do too well against incendiaries.

Nige Cook

Hi Chris,

I've been into the firebombing of Japan in detail from a number of sources. Colonel Tibbets, pilot of the Enola Gay which dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, goes into this in his autobiography The Tibbets Story. Before being put in charge of the 509th at Tinian Island for nuclear attacks on Japan, Tibbets was bombing European cities and saw the immense problems. Tibbets actually advised General LeMay on how to do incendiary raids effectively on Japan. This resulted in the success at Tokyo after a lot of failures. It's incredibly important because Tibbets planned the nuclear attacks with this experience in mind, to maximize the impact.

Oppenheimer predicted 20,000 deaths from nuclear attacks for nighttime raids (nuclear radiation and blast casualties, no direct exposure to thermal radiation), but Tibbets exploited the thermal radiation and also a blast incendiary mechanism by attacking in the morning while people were either outdoors (exposed to the thermal flash) commuting or else cooking breakfasts on charcoal braziers in wooden houses full of bamboo furnishings and paper screens, with obvious results (the plan was fairly similar at Nagasaki, attacked at lunch time):

‘Six persons who had been in reinforced-concrete buildings within 3,200 feet [975 m] of air zero stated that black cotton black-out curtains were ignited by flash heat... A large proportion of over 1,000 persons questioned was, however, in agreement that a great majority of the original fires were started by debris falling on kitchen charcoal fires... There had been practically no rain in the city for about 3 weeks.'

- Secret May 1947 U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey report on Hiroshima, pp. 4-6, U.K. National Archives document: AIR 48/160.

Tibbets found that for incendiary success you need wooden cities because brick houses are 80% incombustible and don't have enough fuel per unit area for firestorms. Second, you can't burn even wooden houses with incendiaries alone. You need to drop a mixture of high explosive (to make holes in tiled roofs, allowing incendiaries to enter the loft spaces) plus incendiaries, or you get nothing. Even when an incendiary did enter a small room, the British Home Office found that only 20% of them actually caused a continuing fire. Out of hundreds of incendiary raids in Europe, only five definite firestorms were produced: Hamburg, Darmstadt, Kassel, Wuppertal and Dresden. Stanbury gives the following data for Hamburg (‘The Fire Hazard from Nuclear Weapons’, Fission Fragments, Scientific Civil Defence Magazine, Home Office, London, No. 3, August 1962, pp. 22-6, British Home Office, Scientific Adviser’s Branch, originally classified Restricted, in the British National Archives: document HO 229/3):

'On the night of 27/28th July 1943, by some extraordinary chance, 190 tons of bombs were dropped into one square mile of Hamburg. This square mile contained 6,000 buildings, many of which were [multistorey wooden] medieval.

'A density of greater than 70 tons/sq. mile had not been achieved before even in some of the major fire raids, and was only exceeded on a few occasions subsequently. The effect of these bombs is best shown in the following diagram, each step of which is based on sound trials and operational experience of the weapons concerned.

'102 tons of high explosive bombs dropped -> 100 fires

'88 tons of incendiary bombs dropped, of which:

'48 tons of 4 pound magnesium bombs = 27,000 bombs -> 8,000 hit buildings -> 1,600 fires

'40 tons of 30 pound gel bombs = 3,000 bombs -> 900 hit buildings -> 800 fires

'Total = 2,500 fires'

Hence, 2,500 house fires occurred in a square mile with 6,000 wooden buildings, and caused a firestorm.

If you look at the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey report 'The Effects of the Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki' it compares the effects of nuclear bombs with all the incendiary raids on Japan. It shows that 93 raids with an average of 1,129 tons of incendiaries and TNT each failed to cause firestorms and only killed an average of 1,850 people each. Tokyo on 9/10 March 1945 was exceptional, in killing 83,000 people in a firestorm due to 1,667 tons of incendiaries and TNT. The absolute number of nuclear casualties depend on controversial factors like whether you include the 40,000 Korean slave labourers present in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or not. (See 'Hiroshima's forgotten victims' in the Manchester Guardian Weekly, vol. 131, 1984, No. 8. p. 18.) But the radiation statistics are well studied with a control group. In 1996, half a century after the nuclear detonations, data on cancers from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors was published by D. A. Pierce et al. of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, RERF (Radiation Research vol. 146 pp. 1-27; Science vol. 272, pp. 632-3) for 86,572 survivors, of whom 60% had received bomb doses of over 5 mSv (or 500 millirem in old units) suffering 4,741 cancers of which only 420 were due to radiation, consisting of 85 leukemias and 335 solid cancers.

It was politics that ended the war, not gross effects from aerial bombardment. The surprise attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki couldn't have been repeated on a third city with similar effect because the Japanese were already stepping up air raid warnings and duck and cover advice to avert burns etc. It was the declaration of war on Japan by Russia which precipitated conditional surrender. At least 40 million people were killed in WWII and the 420 overhyped nuclear attack radiation cancer casualties are 0.001% of that that.

Nige Cook

Hi Brett,

'Aerial bombardment was devastating; at least half a million civilians died from it in WWII, perhaps more than a million. It just wasn’t devastating enough, consistently enough to cause a knock-out blow, as predicted by many before the war; and people didn’t react to being bombed the way they were ’supposed’ to. ... both sides were deterred from using chemical weapons in WWII, but I’m not sure what your point is. You can’t drop a gas chamber on an enemy city ...'

Thanks, my point about chemical warfare is simply that restraint was shown for weapons of mass destruction in WWII, to an even greater degree than it was for high explosive and chemical bombardment. This has implications for other weapons of mass destruction in wars today. Assuming 1 million deaths from aerial bombardment and at least 40 million killed during during WWII, then aerial bombardment accounts for 2.5% of those killed. I agree that people didn't panic and lose all morale the way they were predicted to.

This history is applicable today. In order to produce the kind of overhyped nuclear bombing effects people expect, you'd have to find a city made out of wooden medieval houses like the square mile of Hamburg or 1945 Hiroshima, and drop the bomb when most people are outdoors or preparing breakfast on charcoal braziers that can easily be overturned by the blast and set the houses on fire.

The idea of bigger bombs are significantly more effective was debunked by Lord Penney, who pointed out that a blast wave over an unobstructed desert doesn't behave as in a built up city: each house destroyed depletes at least 1% of the blast energy and after a few hundred houses in a line from ground zero are totalled, the effects don't scale up by the cube-root law any more: there is also an exponential attenuation factor that limits scaling. The actual blast effects in built up areas are less severe in brick and concrete cities than in Hiroshima where fire burned down wooden buildings, and those effects vary only very slowly with yield.

The basis of mass destruction collapses when energy is conserved, which it isn't in the popular source books on predicting the effects of nuclear weapons. Even the apparently solid crater predictions in Glasstone and Dolan are completely false for large weapons because they neglect the energy used to dump material out of large craters against gravity. For example, in the case of a 10 Mt surface burst on dry soil, the 1957, 1962, and 1964 editions of Glasstone's 'Effects of Nuclear Weapons' predicted a crater radius of 414 metres. After 1987, the introduction of physically real gravity effects reduced the crater radius for a 10 Mt surface burst on dry soil to just 92 metres, only 22% of the figure believed up to 1964.

'I’d be interested to know where you get your information about Japanese civil defence capabilities against atomic attack, as they didn’t do too well against incendiaries.'

Japanese civil defense did perform very well after incendiary attacks on 93 cities reported in the unclassified 1946 U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey: an average of 1,129 tons of incendiaries and TNT on each of those 93 cities failed to cause firestorms and only killed an average of 1,850 people in each raid. The three cases where there was failure were Tokyo, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Tokyo was a civil defense failure because the conventional high explosive included in the incendiary bombing loads over a long period of bombing prevented fire-fighting being efficient.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki were civil defense failures due to surprise as documented in 509th commander Tibbet's autobiography: in Hiroshima the air-raid warning sounded at 7 am, and the all-clear at 7:30 am, but the bomb was dropped at 8:09 am. People cooked breakfasts with charcoal braziers in inflammable wood homes, with paper screens and bamboo furniture. Blasted red-hot charcoal and screens in the wooden houses started fires. In Nagasaki, the air-raid siren sounded at 7:50 am but was cleared before the bomb fell. Tibbets writes that for a month before the attacks weather aircraft were sent over the cities daily to ‘accustom the Japanese to seeing daytime flights of two or three bombers’.

This caused civil defense warning and response to get lax to small numbers of B-29s, maximising the effects the the explosions. E.g., many people watched the bomb fall behind windows without taking cover, and received both flash burns burns and then flying glass in their faces when the blast wave arrived. Civil defensein Hiroshima was documented by the secret reports of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey.

For example, the Bank of Japan, Hiroshima branch, was a 3-story reinforced concrete frame building at just 400 m from ground zero. There were no initial ignitions at all by either blast or thermal radiation. However, 1.5 hours afterwards a a firebrand started a fire in a room on the second floor. The survivors in the building simply extinguished the fire with buckets of water! Later another firebrand ignited the third floor, and the survivors this time ran out of water and just shut the doors and allowed it to burn out. The fire did not spread to the lower floors.

This incident is explained in panel 26 of the U.S. Dept. Defense, 'DCPA Attack Environment Manual: Chapter 3, What the Planner Needs to Know about Fire Ignition and Spread', report CPG 2-1A3, June 1973. This report adds that the Geibi Bank Company in the firestorm area of Hiroshima also survived the bomb with no thermal or blast ignitions:

'However, at about 10:30 A.M., over 2 hours after the detonation, firebrands from the south exposure ignited a few pieces of furniture and curtains on the first and third stories. The fires were extinguished with water buckets by the building occupants. Negligible fire damage resulted.'

The civil defense advice Japan issued immediately after Nagasaki, basically advice to duck and cover when seeing lone B-29s dropping single bombs, is well documented (albeit in a politically prejudiced way) in most of the books on the effects on survivors who dismissed it (wrongly) as hard-line propaganda, just as 'duck and cover' advice is generally dismissed after 1977 (when it was dropped from the final chapter of 'The Effects of Nuclear Weapons', which in every previous edition from 1950 on had been a civil defence justification but in 1977 politically was restricted to only effects).

'Why Japan surrendered is still a contentious question. Recently the Soviet invasion of Manchuria has assumed greater importance in the historiography than previously, but the atomic bombs were still crucial. (In the words of one member of the peace faction in the Japanese war cabinet, Hiroshima was a ‘gift from heaven’.) Yes, another atom bomb wouldn’t have been ready for some time, but the Japanese decision-makers didn’t know that.'

It's well documented that the Emperor was holding out in the hope that Stalin would help it negotiate a surrender. That hope was lost when Stalin declared war on Japan, which Stalin did because after Nagasaki because he thought the way was soon going to end, thus Russia had everything to gain and nothing to lose by declaring war at the last possible minute.

This is not a rejection of the effect of nuclear weapons in ending the war: they did that. They pushed Stalin into declaring war on Japan, and in turn that pushed the Emperor into seeking a conditional surrender. Doubtless, the effects of nuclear weapons also had some direct influence on the Emperor and the military leadership, but if you read the published accounts of their discussions (even those in Rhodes, 'Making of the Atomic Bomb', 1986), they aren't convinced that the nuclear attacks are far worse than the Tokyo incendiary raid. All the controversy I've seen has focussed on why nuclear weapons were used at all (thus taking it for granted falsely that they produced more severe effects than non-nuclear raids), not on the mechanism by which their use ended the war. E.g. the BBC history group has been accused of bias in portraying Truman's decision to bomb Japan as a warning to deter Stalin from world domination: http://www.julianlewis.net/local_news_detail.php?id=16

Nige Cook

sorry, first sentence should read '... high explosive and incendiary bombardment...'

Brett Holman

Post authorYes, it's quite hard to start firestorms. Using conventional weapons only a handful were started in WWII despite all the city bombing that went on, and it was generally by accident. By contrast, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki levelled cities and killed tens of thousands of people each: one plane, one bomb, zero Allied casualties. You claim this is 'trivial', apparently because cancer rates of survivors is nothing like as high as popular myth has it. Again, I don't get the point. Nobody at the time was banking on the bombs causing cancer, or indeed even had much idea it was likely. And of course, the fission bombs used against Japan were firecrackers compared with the thermonuclear bombs developed later.

Why is this 'only'? It's 172050 dead (plus, I guess, about twice that wounded) who wouldn't otherwise have been. It's much more 'successful' than the Blitz against Britain, perhaps even than Bomber Command's raids on Germany, on a average deaths-per-raid basis. It does not suggest a particularly efficient civil defence organisation.

Who overhypes this? I've never seen much attention paid to the cancer casualties at all. It's the couple of hundred thousand deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki that grab attention.

What you have to say about incorrect extrapolation from nuclear weapons tests is interesting. But you ought to lay it all out in an article or a book rather than on a blog.

I'm not referring to the long-standing debate about whether the atomic bombs should have been used or not but the more recent discussion about whether the Soviet invasion of Manchuria was more important to the Japanese decision to surrender than the use of the atomic bombs. Tsuyoshi Hasegawa's Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (2005) is key here.

nige cook

Hi Dr Holman,

I think you're writing a book on this (ARP/civil defence in bombing), so I've put online some of the key declassified Top Secret and related reports I've photocopied (all out of copyright) from the U.K. National Archives. These ae mostly relevant to WWII and civil defence. PDF compendiums:

http://archive.org/details/BritishNuclearTestOperationHurricaneDeclassifiedReportsToWinston

At page 87 is an extract from U.K. National Archives document HO 225/12 (Home Office Scientific Advisory Branch): "A Comparison between the number of people killed per tonne of bombs during World War I and World War II". This notes that WWI bombs dropped on Britain (by airships and Gotha bombers) by Germany were mainly 12-50 kg, while WWII bombs dropped on Britain were mainly 150-200 kg (mean 175 kg).

It records that during the 13 June 1916 air raid on London, 69.5% of people were outdoors and were therefore highly vulnerable to the blast of the bombs. During WWII, only 5% of people in Britain were in the open during air raids (e.g. fire observers, firemen, police, etc.), 60% were under cover such as under tables in houses, and 35% were in shelters. Being in a house was 3.5 times safer than being in the open; being in a shelter was twice as safe as being in a house or 7 times as safe as being in the open.

I have also scanned in and included in this PDF the originally Top Secret reports (which even Thatcher refused to publish to bolster civil defence in 1983, despite a request in the House of Commons) on Britain's Operation Hurricane nuclear test at Monte Bello and the reports to PM Winston Churchill on the threat of a Russian bomb being smuggled into a harbour. This was why WWII Anderson shelters and concrete cubicles were exposed to the Hurricane.

The point is, WWII civil defence precautions stood up very well to nuclear weapons effects, both in Hiroshima/Nagasaki (where nobody was actually in the shelters) and in Australian trials. This fact continues to be ignored on both sides of the civil defence debate, largely because of disarmament bias, but also because the full facts are essentially still unpublicised. This is an exact duplication of the situation in the 1920s and 1930s, where gas warfare civil defence effectiveness data was kept secret, and the public was issued with easily ridiculed advice:

http://archive.org/details/ArpBooksTechnicalCriticismsOfGasCivilDefence

“The Cambridge Scientists’ Anti-War Group” (led by an editorial committee of 11 scientists, headed by J. D. Bernal), “The Protection of the Public from Aerial Attack, Being a Critical Examination of the Recommendations Put Forward by the Air Raid Precautions Department of the Home Office”, first published by Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, on 12 February 1937, reprinted the same day. They report on page 21: “the time taken for the gas to leak out to half its original value was measured in four rooms – the basement of a shop, the dining room of a semi-detached house, the sitting room of a Council house and the bathroom of a modern villa. … the leakage half-times of these rooms were 2.5, 2.5, 3.5 and 9.25 hours respectively.” Rooms with closed steel frames (or double glazed) windows gave the best protection.

On page 41, the Cambridge Scientists admit that since the gas is wind carried: “the gas will not remain for long periods in any one place except on still days [when it won’t be blown over large areas].” For example, a massive gas cloud 1 mile in diameter blown by a typical 10 miles per hour breeze will only spend 1/10 or 0.1 hour over any given location. This means that the half-penetration times of carbon dioxide gas (a small molecule, with a faster speed and penetration rate than the larger, slower molecules or Nazi tabun nerve gas or mustard gas) of 2.5-9.25 hours in British houses are much larger than the 0.1 hour time taken for the gas cloud to pass by. Consequently, very little gas can penetrate into a British house in this time. However, the Cambridge Scientists fail to point this fact out. They are politically biased and this is proved by their deliberately obfuscating account of the phosgene gas disaster in Hamburg on pages 41 and 109.

On page 42 they suddenly switch from discussing gas bombing to assuming that gas is released slowly (50% every 10 minutes) from gas cylinders as in the first use of chlorine in World War I battlefields. This spurious change of goalposts from bombs to cylinders is completely deluded because any cylinders of gas dropped from aircraft would explode on impact, like bombs. The slow release of gas from cylinders gives more time for people to take precautions, such as taping up cracks in window frames in a house. On page 58, the Cambridge Scientists then resort to more fantasy, by assuming that incendiary bombing will set everybody’s house on fire in an air raid, forcing people outdoors, when they will be gassed by gas bombs. This is “backed up” by mere unproved and false assertions such as (on page 59) the statement: “whoever deals with them [incendiary bombs] will require, almost certainly, simultaneous protection against gas.” There is no scientific evidence given for this assertion that it is “almost certain” that gas bombs will be used in conjunction with incendiaries. It is merely guesswork, disproved in WWII.

Page 68 cites anti-civil defence propagandarist Philip Noel-Baker as claiming that 9 aircraft could cause 1,800 fires which would spread like the San Francisco (1906) or Tokyo (1933) earthquake-caused great fires, leading to “the probable amalgamation of separate outbreaks into a vast conflagration.” This is not “scientific evidence” and has no model or detailed evidence for modern Western (non-wood frame) cities, but mere “authority”-style assertion, and was proved false in WWII.

Page 70 summarizes the sophistry so far: “… it would be possible on the average to remain alive for about three hours in the ‘gas proof’ room; in other words the ‘gas proof’ room is not gas-tight.” No mention that even a massive 1 mile wide gas cloud only takes 0.1 hour (6 minutes) to leave the vicinity of your house in a typical 10 miles per hour breeze! Page 71 again offers similarly spurious fear-mongering: “… it is pointed out that gas-masks only protect the face and lungs … mustard gas … attacks the whole surface of the body.” This “argument” against gas masks ignores the gas proof room!

Page 109 in the Cambridge Scientists’ book gives a completely misleading treatment of the Hamburg phosgene accident of 1928, when 11 tons of phosgene was released into a populated area by accident and without warning in summertime (when windows were open), killing just 11 people! The Cambridge Scientists omit to give the percentages of people killed, and point out the maximum lethal distance was 2 kilometres, with injury up to 2.7 kilometres downwind. They then try to obfuscate the facts by assuming that gas is released from cylinders, not bombs, to exaggerate the hazard indoors.

On page 56 of this PDF, there is another publication by the same Cambridge Scientist’s Anti War Group, issue 13 of “Fact” magazine, April 1938, “Air Raid Precautions: The Facts”. This makes their prejudice clear on page 17 of “Fact” (page 59 in the PDF document): “There is no necessity for any such measures, if the Government adheres to a proper foreign policy.” In other words, disarm to prevent war with the Nazis, then you can be proud of being anti war and forcing peaceful coexistence.

Page 71 of our PDF gives J. B. S. Haldane’s September 1938 book “ARP”. Haldane with his father invented the first war gas mask in 1915 after Germany used chlorine gas. On page 18 (page 83 of the PDF document) Haldane states: “These gases can penetrate into houses, but very slowly. So even in a badly-constructed house one is enormously safer than in the open air.” On page 21, he points out that liquids (mustard agent or nerve agent spray droplets) sprayed from high altitudes are liable to evaporate and be blown away and diluted harmlessly before ever reaching the earth’s surface. On page 22 he discusses the Hamburg phosgene accident objectively. On Sunday 20 May 1928, 11 tons of phosgene was released from a burst container in the Hamburg docks and was blown over the suburb of Nieder-Georgswerder: “Most of the victims were out-of-doors, playing football, rowing, or even going to vote in an election. The windows were open, so a few people were killed indoors … There would probably have been nil [casualties] had the people received ten minutes’ warning, so that they could have got into houses and shut the windows. No doubt enemy aeroplanes could have dropped the gas in a more thickly populated area. But they would not have taken people by surprise … Eleven tons of gas could be carried in about fifteen tons of bombs [and more casualties could be caused by fifteen tons of high explosive bombs than the 11 killed by the Hamburg phosgene gas disaster].”

On pages 94-5 (pages 101-102 of this PDF), Haldane summarises the Home Office White Paper Circular of 31 December 1937, “Experiments in Anti-Gas Protection of Houses” which gives the experimental tests of the anti-gas advice using mustard gas liquid in trays around a house: “Animals outside were badly affected. Of those in an unprotected room none were seriously harmed. Those in a ‘gas proofed’ room remained normal, and the amount of mustard gas in it was measured by chemical methods. It was found to be so small that a man could have remained in it for 20 hours without harm, even if unprotected by a respirator.”

On page 248 (page 106 of the PDF), Haldane states: “Certain pacifist writers are severely to blame for our present terror of air raids. They have given quite exaggerated accounts of what is likely to happen.”

http://archive.org/details/WhyWar_546

Cyril Joad's 1939 "Why War" propaganda book. Joad led the infamous 1933 Oxford Union argument for the motion "This country will not fight for King and Country", which sent dictators everywhere the message that Britain was turning pacifist and weak. On page 71, Joad attacks Winston Churchill's call for an arms race to preserve peace. Joad's outlook on war as a disease that can be eradicated by a simple moral refusal to fight is the overriding outlook of the Cambridge Scientists' Anti-War Group. However, it's hardly moral to make up lies against civil defence in order to "justify" pacifism.

http://archive.org/details/NuclearWeaponsEmploymentManuals

This compiles extracts from all Cold War declassified nuclear weapons employment manuals, showing how collateral damage and fallout is controlled by the yield and height of burst. I hope that some of this information is of use.

Kind regards,

Nigel

Brett Holman

Post authorNigel:

We've already had lengthy discussions elsewhere here, so I won't rehash my disagreements with your approach again. Instead I will accept your comment in the spirit in which it is intended and thank you for putting these resources up on the web. Might I be churlish and suggest one thing, however? They would be much more useful for others if you scanned in the whole books and not just the pages which bear on your own interests. There's more to ARP books than just ARP, in other words. As I say, that is churlish of me, as it's a lot of work to scan in these works and make them available, and I'm too lazy to do it! And even parts are better than nothing; I do have a copy of the chunk of O'Brien's Civil Defence you put up, so thank you for that. (It puzzles me why the UK government doesn't scan the official histories in and put them on the web itself, as has been done here in Australia.)

Pingback:

SEEING THE WORLD THROUGH BOOKS » Blog Archive » Guy Saville–THE AFRIKA REICH