Since my AAEH talk is in four days, I'd better start actually putting the pieces I've scattered over this blog together into something (ideally) coherent which can be presented in 20 minutes (with 10 for questions). So here's a stab at a plan:

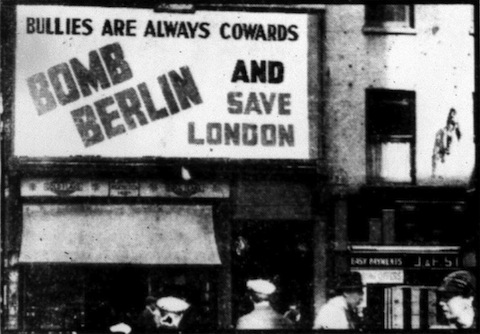

- First thing is to explain what I'm talking about: the public debate about reprisal bombing of German cities during (and for) the Blitz, especially September and October 1940. A definition of reprisals would be useful here; here's a contemporary one from A. L. Goodhart, What Acts of War are Justifiable? (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1941), 25:

The essence of reprisals is that if one belligerent deliberately violates the accepted rules of warfare then the other belligerent, for the sake of protecting himself, may resort by way of retaliation to measures which, in ordinary circumstances, would be illegal.

That's a legal definition; it excludes the desire for mere revenge as illegitimate, but of course this was an important motivation for many.

- Next comes the problem: I will discuss the existing historiography on the reprisals debate, showing that the consensus is that the British people did not demand reprisals, and those who did weren't the ones who were bombed. (Only Mark Connelly differs on this point to any substantial degree.) I think this is wrong; in fact the desire for reprisals predominated at least among those who cared enough to voice their opinion, and possibly among the population as a whole, if only slightly.

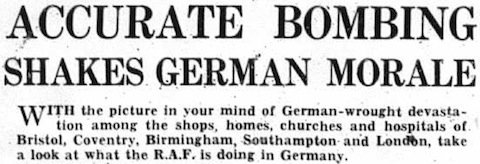

- Now on to the first of the important bits: the shape of the reprisals debate. I'll discuss the two major axes of opinion: morality and effectiveness, and give some examples. I'll also point to an important subset of the reprisals demand, reprisals after notice. And I will show that the near-universal assumption was that Bomber Command was capable of carrying out precise and devastating air raids.

- The second of the important bits: assessing how popular the demand for reprisals actually was. Here I will discuss the BIPO opinion poll data, letters to the editor, and hearsay, setting these in the context of the editorial positions of the newspapers concerned. These lines of evidence all point towards public opinion being in favour of reprisals.

- Now to explain it all, largely in terms of pre-war ideas (which wartime reporting had done little to change by this point), with reference to the previous war, the knock-out blow theory, the bomber will always get through and air control. Essentially, the pre-war belief in the power of the bomber was the reason why there was a debate about reprisals at all; if it had been realised just how weak Bomber Command really was the question would not have arisen.

- Finally, to sum up: overall the British people, I believe, did want reprisal bombing during the Blitz. Any questions?