A few weeks back, @TroveAirBot found a short article from the Port Lincoln, Tumby and West Coast Recorder entitled 'Dropped From the Clouds':

A balloon which ascended from the Welsh Harp, Hendon, on October 14 [1904], carried with it into the clouds a large flying machine.

As no one was in the car of the balloon or in the flying machine, the experiment was conducted with a minimum of danger.

No such untoward incident occurred, however, and the experiment, which is the first of a series being carried ont by Messrs Spencer Bros, in order to test the powers of Senor Alvares's aeroplane, was conducted with marked success.

The balloon, inflated with 25,000 cubic feet of coal gas, carried the aeroplane to a height of 3,000 feet. At that altitude the machine was automatically liberated. Three thousand feet below a little group of experts watched its movements.

Carrying the weight representing that of an average man, the airship made its way earthwards. At first it plunged rather excitedly towards the watching scientists, bat then, recovering itself, it proceeded steadily in a horizontal direction for a considerable distance. The propellers revolved rapidly, and the machine kept its balance in a manner which augured well for the success of the experiments which are to be made later with a man on board instead of a dead weight.

After travelling at a high speed over the country for a mile or so, the airship came to earth in an open meadow, where it was at once recovered quite uninjured.((Port Lincoln, Tumby and West Coast Recorder, 17 March 1905, 7.))

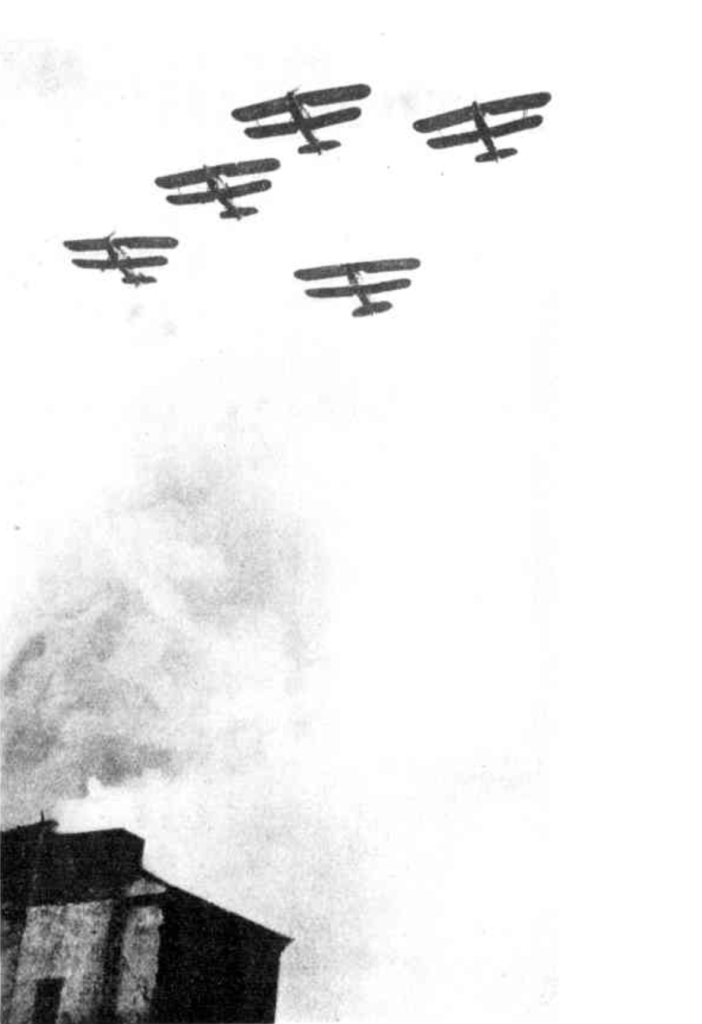

This caught my eye. It's not unusual (especially on this blog) to find aviation activity at Hendon, the most famous aerodrome in Britain before 1914 and home of the RAF's aerial theatre for most of the 1920s and 1930s. But it is unusual to find any this early: this was in 1904, which is five years before there was actually an aerodrome at Hendon, and for that matter less than a year after the Wrights' first powered flight.

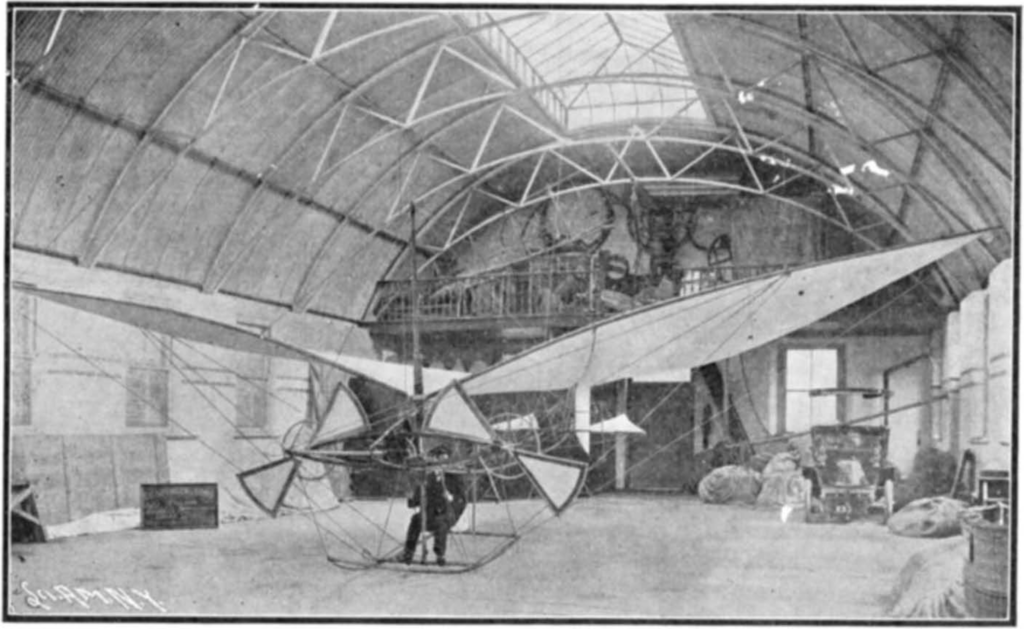

There was, in fact, aviation at Hendon before the aerodrome: in particular, in 1908 H. P. Martin and G. H. Handasyde (as in Martinsyde) built an unsuccessful monoplane 'in the unused ballroom of the Old Welsh Harp public house at Hendon', while Everett, Edgecumbe & Co., a Hendon instrument firm, built another, even less successful, one on the site of the future aerodrome. (Local lad C. R. Fairey -- as in Fairey -- got his start in aviation on that one.)((David Oliver, Hendon Aerodrome: A History (Shrewsbury: Airlife, 1994), 7.)) But according to David Oliver, author of the best history of the Hendon aerodrome, Martin-Handasyde and Everett, Edgecumbe represent the beginning of heavier-than-air flight there. He doesn't mention this 1904 unpiloted flight by Señor Alvares's flying machine; nor does Charles Gibbs-Smith, the authority on early aviation.((Ibid; Charles H. Gibbs-Smith, Aviation: An Historical Survey from Its Origins to the End of World War II (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1985).))

Of course, neither Oliver nor Gibbs-Smith had access to digitised newspaper archives, so they can hardly be blamed for missing one particular obscure flight. But nobody else seems to know about it either, or at least some desultory googling throw up nothing about it. This made me curious to see if I could find anything more about this mysterious aeroplane or its mysterious inventor. I managed to find one, but not the other -- as I will discuss in the next post.