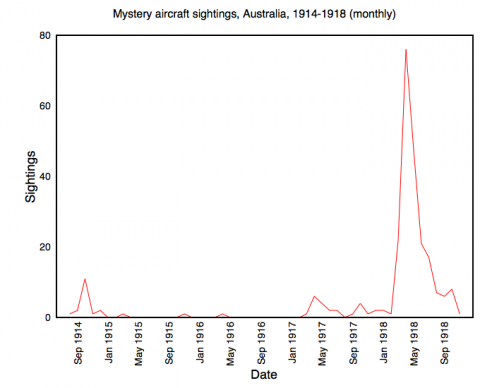

So, to the mystery aeroplane sceptics. Again, there are some sceptical opinions to be found in the press and police reports, but relatively few. Very early on, the Age, one of Melbourne's leading newspapers, wrote on 25 March 1918 that

the defence authorities are inclined to laugh at the story told by Police Constable Wright, of Ouyen, that at Nyang on Thursday last [21 March] he saw two aeroplanes flying in a westerly direction at a high altitude. The constable insists that he was not mistaken, but the authorities, being able to account for the movements of all Australian aeroplanes, jokingly suggest that the constable's story is on a par with those told about the Tantanoola tiger.1

It did go on to say that 'the authorities very rightly recognise that it would be unwise not to investigate [...] and inquiries into the reported occurrence are being made by special intelligence officers'.2 This was true, though in the event the 'special intelligence officers' (actually Detective F. W. Sickerdick, Victoria Police, and Lieutenant Edwards of the Royal Flying Corps) weren't despatched from Melbourne until 13 April as part of a broad sweep around western Victoria interviewing witnesses and suspects which took several weeks to complete. The conclusion of Sickerdick's report was unsurprisingly negative:

In my opinion and from the observations taken and from information received, the opinion of the residents, and the country travelled through, I do not believe that aeroplanes ever flew over the MALLEE, and I believe the objects seen at different times and by different people, were either hawks or pelicans.3

- Age (Melbourne), 25 March 1918, copy in NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066. The article also refers to reports 'earlier in the war of a mythical fleet of eight enemy aeroplanes which flew over Hobart'. This would seem to refer to an incident in October 1914 when 'a battery of artillery in training near Hobart observed "several aircraft"': NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066, minute, Director of Military Intelligence (Major E. L. Piesse) to Chief of the General Staff, 'Report of aeroplane at Towamba, N.S.W.', 16 May 1917. [↩]

- Age (Melbourne), 25 March 1918, copy in NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066. [↩]

- NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066, report, Detective F. W. Sickerdick (Victoria Police) to Major F. V. Hogan (Intelligence Section, General Staff), 1 May 1918. [↩]