This is from a document issued by the Air Council in October 1918, ‘Identification marks on all aircraft’, FS Publication 89. I think it’s available from the National Archives in London as AIR 10/128 and AIR 10/129, but I found it in the National Archives of Australia as NAA: A1194, 19.03/6255, and because I paid to have it digitised you can see it on their website. It portrays the national identification markings for every country from America (a red, blue and white roundel) to Turkey (a black square inside a white square). I’m not sure how germane it is to the mystery aircraft scare earlier in the year: it probably wouldn’t even have arrived in Australia before the Armistice. But it did follow a series of official determinations in the autumn about how to recognise German aircraft and, indeed, how to recognise aircraft at all.

There were two parts to this, one private and one public. The public part came on 23 April (the watershed date in the press coverage, perhaps not coincidentally) in public remarks by Senator George Pearce, the Minister for Defence, ‘in reference to various reports of aeroplanes having been seen in certain places in Victoria’:

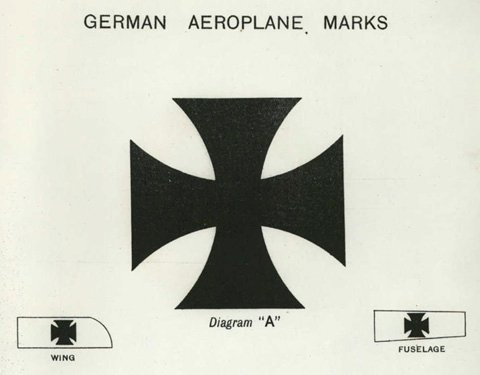

All British and Australian aeroplanes are visibly marked with three concentric circles of colour — red, white, and blue. German planes are marked with large black crosses in the shape of the “iron cross.” Privately-owned planes are not so marked, and such marking on them would be illegal. Any German or other enemy subject using an unmarked plane, or one with British markings, is subject to the penalty of a spy.1

Pearce’s emphasis upon the national markings is odd. Very, very few of the mystery aeroplane reports mention anything about markings (I think there’s one where an aeroplane had British roundels, but I can’t find it at the moment [edit: of course, having said this I found another example almost immediately, albeit dating to a week after Pearce’s comments]). Perhaps the idea was to undermine the idea that the aeroplanes, if they existed, were from a German raider but instead were operated by German spies or sympathisers.

The private determination was made by the Officer Commanding, Central Flying School, Point Cook. This document, ‘Aircraft. Notes for guidance in determining their presence’, was circulated in May to other arms of government including, at least, the Royal Australian Navy (which added a paragraph for its own use, noting the different float arrangements of German and ‘English’ seaplanes) and the Victoria Police (which published it for the benefit of its officers in the Victoria Police Gazette).2 The CFS notes used five different criteria:

- sound: a low-flying aircraft sounds like a ‘thrasher’ (or threshing machine), between 2000 and 4000 feet like a motorbike from half a mile away; up to 8000 feet ‘similar to droning of a sawmill’ from a like distance.

- visual appearance: up to 1000 feet,

aeroplanes can be distinctly seen. Movements of controlling gear, wing tips, and rear portions of tail will be visible. Pilots and number of passengers can be observed if the machine is not directly overhead.

Above 1000 feet, no such movements would be visible.

- visibility: the ‘British identification mark of red, blue, and white rings’ can be seen from directly underneath up to 2000 feet;

When flying with clouds as background, machines will show up with black appearance; when suddenly turning or moving into bright sunlight, shape may be indistinguishable, and only a flash like metal seen.

- relative size: if the aircraft is flying at a height of 3000 feet overhead, there is no ‘room for doubt as to the identity of the object seen’. But ‘Size diminishes approximately in proportion to height until the machine may appear as a bird flying at a great height or a mere speck’.

- ‘Marks on ground where machines have landed or taken off’: usually none, except in sandy, muddy or ploughed soil in which tracks from rubber tyres and skids would be visible. A ‘Maurice Farman type‘, for example, would leave tracks similar to a ‘light Ford’.

This was the advice of the experts; but it contained the admission that even experts could be fooled:

At certain altitudes, and viewing from certain angles, a hawk gliding or soaring has the identical appearance of certain aircraft […] In support of this it is stated that instructors at C.F.S. have themselves been temporarily deceived by the appearance of a hawk when machines have been flying.

So, ‘noise in conjunction with view is the surest guide to identification […] Special attention should be paid to gradual fading of noise as object disappears’.

The CFS notes were circulated just as the main phase of the mystery aeroplane scare ended, so perhaps they had an effect by increasing the scepticism of rural policemen who were usually the first point of contact for witnesses. The fact that they were compiled and distributed at all shows just how little experience most Australians, especially but not only the civilians, had had with aeroplanes by 1918. Clearly it could be assumed that they would have encountered motor cars and motor bikes, as these were used as points of reference, but not that they would be correctly able to interpret an unidentified flying object.

The forced landing of a military aeroplane near Wonthaggi on 11 May showed the novelty of flight. The pilot, Captain Frank McNamara VC, sought and obtained assistance from the townsfolk (a guard of returned soldiers, the use of a local grandee’s motor car) but had to stay overnight while repairs were effected. A Melbourne Herald report (passed to the censor, I doubt it was published) demonstrates how intrigued people were when encountering a real aeroplane:

On Saturday the unusual occurrence of an aeroplane hovering over the town was witnessed by many […] On Saturday afternoon many people visited the paddock, and the majority for the first time in their lives saw at close quarters a flying machine […] A trial fly was made on Sunday morning, and church goers and others who were up and about were treated to the novel sight of a plane droning overhead […] There were many people present who had arrived per car, or vehicle, and the element of flying was explained to an interested number by Captain McNamara, before starting on his homeward journey […] The incident created great interest and stimulated many young Australians with a desire to accomplish the art of flying that they might be of service to their country.3

Incidentally, this aeroplane was returning to Point Cook after carrying out an unsuccessful search for raiders off the Gippsland coast, instituted as a result of the multitude of mystery aeroplane reports from that region. McNamara, who eventually retired from the RAAF in 1946 as an air vice marshal, had been invalided back to Australia and discharged as medically unfit, but was recalled to the colours in order to carry out the search. And he himself had inadvertently caused one mystery aeroplane report on 20 April while flying from Point Cook to Yarram to begin the search!

So I was supposed to be talking about how the mystery aeroplane scare was propagated after the newspapers stopped writing about it. Maybe next time!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Sydney Morning Herald, 24 April 1918, 11; also Argus (Melbourne), 24 April 1918, 9. [↩]

- NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066/378, OC Central Flying School, ‘Aircraft. Notes for guidance in determining their presence’, Naval Board annotated copy, 7 May 1918; Victoria Police Gazette, 16 May 1918. [↩]

- NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066/378, ‘Aeroplane over Wonthaggi’, 20 May 1918. [↩]

Excuse my ignorance on the matter, but did Australia have a legitimate problem with German spies and sympathizers trying to undermine the Australian war effort?

Pingback: Airminded · Fear, uncertainty, doubt — III

That’s a good question. The government certainly thought there was a problem, at least with sympathisers (for example, after the Bolshevik revolution there were grave suspicions about the pacifists and socialists taking German money, and dark mutterings about ‘organised enemy propaganda’). By 1918 it didn’t seem so concerned about spies, but by then it had already interned most of the likely candidates (i.e. German subjects, naturalised Australians of German birth, even a few second and third generation migrants). But I haven’t seen any evidence yet of any serious or organised attempts by these ‘Germans’ to undermine the war effort. I’ll be looking at Germanophobia in a future post.

Thanks, Brett. I look forward to your post on Germanophobia.

Great find Brett. There’s lots to tease out in that recognition booklet. Why was it in alphabetical rather than diagram order? (It’s not much chop for identifying markings you observe, rather it works identifying the marking there should be if you already know the nation.) They certainly were still obsessed (as it was a civil threat) by airships, weren’t they? And what a bizarre selection of nations!

I’ve a very similar format version in Janes All the World’s Aircraft 1945, obviously updated.

The irony is whether the list arrived in October 1918 or after the war’s end, the markings for German aircraft were outdated. Of course any aircraft that arrived in Australia would’ve set off some time earlier with presumably the pre-April 1918 markings.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balkenkreuz

However it was pretty poor effort by the Air Min to be issuing pre-April 1918 markings 6 months later. It’s in notable contrast (in the colour scheme research I’ve seen and carried out) how remarkably up-to-date colours and markings were kept in the field in both World Wars, even in the roughest conditions.

JDK:

Oh, I didn’t even know Germany had changed its markings in 1918! That’s a bit embarrassing.

I did wonder about the choice of countries. Presumably most of the world’s air services are included but it’s easy to think of some which aren’t (e.g. Finland, Mexico). The Russian ones are odd too, they are the pre-revolutionary colours. It seems the red star was already in use by this time by the Bolsheviks and White forces used a variety of markings, possibly none matching the ones shown here. Okay, so maybe accurate information was hard to get out of the civil war zone, but then maybe a note to this effect would have been in order!

And the airships. Only one German airship is shown, with just a side view, whereas there are several different French and British types (no Italian) portrayed. But there were about a dozen different Zeppelin variants built during the war, not to mention whatever Schütte-Lanz was doing. Perhaps Zeppelin silhouettes were deemed sufficiently similar to each other, and of course again information would be hard to come by (the one shown is L59, which was captured intact).

So I wonder what it was intended for. Perhaps it wasn’t intended to be used itself in the field, but to serve as the raw material for more useful/simplified instructions? Or maybe, as the war’s end was near, it was to have some function in the armistice/post-war period, in disarmament or demobilisation or civil aviation? Presumably there is some documentation explaining what it’s for somewhere…

I’ve produced documents just like this one, while I was parked safely out of the way of causing trouble, and awaiting a new role or redundancy…