... are all very far away. But for now, there's a nice write-up by Emma McFarnon of my commercial bomber research in the news section of History Extra, the website for BBC History Magazine.

Gaming the knock-out blow — II

So, I want to construct a knock-out blow wargame. In my PhD/book, I define an ideal knock-out blow from the air as having six key characteristics. Three of these describe the attack itself: surprise, scale, and speed. Three describe what it destroyed: infrastructure, morale, and civilisation itself.

Starting with the attack, as this will define most of the actual mechanics of the game:

- Surprise. An attack would be next to impossible to detect. Strategically, an attack would likely come without any warning; the aggressor would be able to time the offensive for maximum effect, and the defender would not be mobilised. Even if an attack is expected, incoming bombers could not be detected before crossing the border, which in the British case means that the best that could be done would be to mount inefficient standing patrols to try to intercept them before they reached London, or attempt to catch them on the way back after unloading their cargo. And even then, the bombers would be hard to find, and able to defend themselves very effectively. Bombers will be the most important units in the game, therefore; fighters might even be abstracted out into the combat system. Also, if the initial attack does not incapacitate, then the defender would be able to launch its own raids on the aggressor, so both sides will need to have bombers.

- Scale. The aerial fleets involved would be massive compared with the strategic bombing campaigns of the First World War, maybe even those of the Second, with hundreds, thousands or even tens of thousands of bombers. Some of these could be commercial bombers, airliners converted to military use, which might be a bit less effective than purpose-built bombers, but not by much. The low interception rates mean also that there would be little wastage. So there might be a lot of units, though the tendency to fly en masse might mitigate this. It depends on the scale.

- Speed. A knock-out blow would operate very quickly: months, weeks, perhaps even days. This factors into the length of a turn. An entire knock-out blow could be simulated in, say, 15 turns of a week or so. Note, however, that at this scale it would take much less than a turn for bombers to reach the target. So a strategic level game like this would not involve units flying around the map, but rather they would be committed in an abstract sense to a target or even a theatre. They might not even be represented as counters at all, but as a numeric force level, which moves up and down according to attrition or production (which could be a factor at this scale). You might not even need a map (though if there are multiple theatres it might help). So, quite abstract. An alternative would be to have a smaller scale game, simulating something like one day in the war, and turns being maybe two or three hours. Then you could do the more familiar, and perhaps more accessible, style of game with units moving around the map and opposing units trying to stop them. Another level would be the tactical one, fighters vs bombers. At this scale, a game might not be very different from the historical reality, since it is a given that interception has taken place. But bombers in formation would be much more capable of self-defence, even without escorts (which were generally not thought necessary).

Turning now to the effects of a knock-out blow, the question is whether to simulate these directly or abstractly. It would be possible in principle to simulate a nation's industries, communications, resources, ports and civilian morale, and the interdependencies between them. Attacking any of these would have knock-on effects, and eventually the cumulative damage would cause society to break down completely. At this point, if not before, effective resistance would cease and the knock-out blow has succeeded. Factories, power plants, ports, railway and road nodes, administrative centres, etc, could be marked on the map and selected as targets; civilian morale is obviously more abstract, but equally obviously attacking population centres would be the best way to attack morale. (Hello, London.) Alternatively, all these targets could be taken off the map and damage to each type tracked by moving a counter along a track. Much easier, though perhaps less fun. Again, it would probably depend on the scale of the game itself, and whether there is a map at all. Either way, some way of representing the knock-on effects would be needed; perhaps when damage to one target system reaches a certain level then damage could be added to all of them. A similar mechanism could be used to determine the degradation of a nation's fighting ability, with production falling off as the knock-out blow proceeds, for example. (Raids directly against the enemy air force could also be undertaken, which might degrade it more rapidly but at the cost of passing up an opportunity to bring a knock-out blow closer.) Or all of that could be emulated much more simply with a victory point system.

So this gives some idea of the considerations involved in designing a game simulating the knock-out blow, not as it would have been fought, but how it was thought it would have been fought. Some things have become clearer. The key thing is decide the scale of the game, since war looks different at different scales. This is why Philip Sabin's concept of nested simulations is useful: two or three games are better than one (at least if your goal is enlightenment rather than enjoyment). In this case, there's a strategic game with turns of a week or so, and a large-scale map or no map at all; an operational game lasting a day and with a map covering the parts of each combatant reachable by its opponent's air force; and a tactical game at a much smaller scale, with turns lasting seconds or minutes and units of individual aircraft, say. As I've suggested above, I think this tactical game would tell us less about the knock-out blow than the other ones, so henceforth I'll concentrate on the operational and strategic games.

Acquisitions

Joanna Bourke. Dismembering the Male: Men's Bodies, Britain, and the Great War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. A now-classic gender analysis of the impact of the First World War on masculinity -- mostly in social and cultural terms, but the first chapter is entitled 'Mutilating' so sometimes the impact is quite literal. Other topics include the change in male identities occasioned by the much more intense official and public interest in the male body, and the postwar sanitisation of all the death and suffering in the form of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (which seems natural enough to us now, but supposedly the bones of the dead at Waterloo were turned into fertiliser only a century earlier).

Peter J. Dean, ed. Australia 1943: The Liberation of New Guinea. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2014. Having read Australia 1942 (2012), I'm keen to find out what happened next. As the title indicates, the perspective is Australian, but there are also chapters on Japanese and American strategy alongside the analyses of the land campaigns in New Guinea. There are also chapters on the RAN and the RAAF in 1943, but this is where I have reservations. The one on the RAAF is by the same author who did the corresponding chapter in Australia 1942, a simple narrative of the aerial campaign, the battles and losses involved. There's nothing wrong with this in and of itself, but the rest of Australia 1942 is much more analytical and pays much more attention to the strategic, logistical, administrative (etc) contexts. The chapter on the RAN was up to this standard; the one on the RAAF was not. Australian airpower history often seems to miss out like this.

Robert and Barbara Donington. The Citizen Faces War. London: Victor Gollancz, 1936. While certainly very sympathetic to pacifism, conscientious objection and war resistance, in the face of the knock-out blow from the air the Doningtons end up plumping for an international air force by way of internationalised civil aviation (and maybe the air pact). Robert later became a respected academic musicologist and early music expert; not sure about Barbara.

Margot A. Henriksen. Dr Strangelove's America: Society and Culture in the Atomic Age. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1997. Argues that the American countercultures of the 1960s were primarily a response to nuclear weapons. Sounds like a bit of a stretch, but as the book covers everything from atomic bomb shelters as well as youth rebellion, it should be fun.

Spencer R. Weart. Nuclear Fears: A History of Images. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1988. This has some overlap with the preceding book, but lacks the contentious hypothesis, covers most of the 20th century (and at least glances outside the United States) and tries to be comprehensive with respect to the various concepts about and responses to nuclear weapons in the public sphere (including death rays and UFOs). In some ways this is reminiscent of what I attempted to do in my PhD/book for the (conventional) bomber -- it would have been useful to have had this, say, eight years ago, especially as Weart provides an appendix on his methodology.

Found: one holy grail

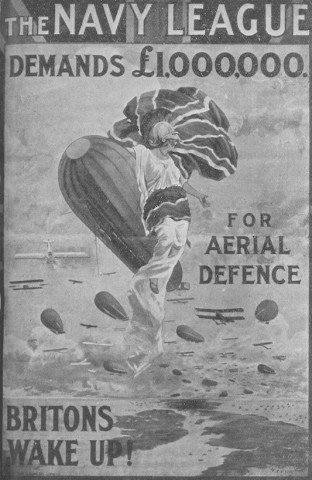

This is the poster produced by the Navy League in 1913 as a key part of its campaign to force the government to increase the amount it spent on military and naval aviation -- or as the poster itself puts it, rather more succinctly:

THE NAVY LEAGUE

DEMANDS £1,000,000.

FOR

AERIAL

DEFENCEBRITONS

WAKE UP!

Describing this poster as a holy grail is somewhat of an overstatement, but it had been proving elusive. I'd read a description of it in the popular press, and found some information about where it was distributed and how much it cost in the Navy League archives, but I hadn't managed to find an actual reproduction of it until I looked at The Navy, May 1913, 135. The official organ of the Navy League was always a likely bet, but when I visited the UK last year, the British Library's copies were unavailable due to the move from Colindale to Boston Spa, and the relevant volume in the Navy League archives was missing. So, naturally, I found a copy in the State Library of Victoria on a quick visit during my holidays.

The description I'd already had turns out to have been perfectly accurate, and so arguably being able to see the design rather than read about it adds little (though the lines of airships and aeroplanes rising up behind Britannia might suggest it an influence from the Illustrated London News). But it will make a nice illustration for an article -- and even nicer if I can find a colour version...

Acquisitions

Joan Beaumont. Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2013. With the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War looming, it's high time we had a book like this: a synoptic overview of the whole of Australia's war, from the fighting overseas to the conflicts at home, from why we got into the war to what we got out of it. Sadly, no mention of mystery aeroplanes that I can see.

Arthur Marder. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow. Volume 1: The Road to War 1904-1914. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2013 [1961]. The classic account of the Royal Navy and the naval arms race with Germany before 1914. Dated now, no doubt, but still influential and still a good source for a lot of boring but necessary facts. Four more volumes cover the actual war years, if you like that sort of thing.

Gaming the knock-out blow — I

As I discussed recently, Philip Sabin's Simulating War: Studying Conflict through Simulation Games (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2012) is primarily about using wargames to understand past wars. This is sensible; apart from the obvious benefit of helping us to understand history better, there's also the useful featurethat there are some facts to go on -- this war, campaign or battle happened once before, so we know something about the forces involved, the terrain it was fought on, the dynamics of combat at the time, and so on. Sabin does occasionally discuss wargaming future conflicts, though mainly in the context of wargaming in the military, where refighting the last (or worse) war is of limited interest.

However, I've been thinking about how to wargame something which is not quite a historical war, and not quite a future war: the knock-out blow from the air. This never actually happened in the past, but for a time was thought to be what might happen in the future. Precisely because of this, a wargame of the knock-out blow could be extremely valuable in demonstrating just how far it was from the reality of aerial warfare. But also precisely because of this, it would be difficult to find the information needed to design the game.

Difficult, not impossible. In fact, I've already done most of the work needed. Part of my PhD and forthcoming book involves a reconstruction of an ideal or consensus form of the knock-out blow theory as it was articulated in the airpower literature from the First World War to the Second. So I could use this as the basis for a wargame showing not what would have happened, or even what could have happened, but what people thought was going to happen in the next war.

Well, that's easier said than done. As Sabin discusses, there are many ways of representing warfare in a wargame, and hence many choices to be made about the maps, the counters, and most importantly the rules. How do this? While I have a reasonable amount of experience playing wargames, I have none designing them. One thing Sabin suggests is starting with an existing game on a related topic, and adapting it to suit or at least borrowing useful elements. Now, as far as I know, there aren't any other wargames simulating the knock-out blow, or for that matter strategic aerial warfare in the interwar period.1 So three realistic options come to mind. One is to start with a game set in the First World War, and project it forward. I have a couple of these: The First Battle of Britain and Airships at War 1916-1918. The second is to start with a game set in the Second World War, and project it backwards. Again, I have a few to work with here, including RAF and The Burning Blue. These approaches both have the advantage of the games being at appropriate scales, and of simulating the sorts of dynamics and tradeoffs inherent in aerial warfare. They have the disadvantage, of course, of being based on historical reality rather than contemporary imagination. The third option, then, is start with a game simulating nuclear warfare, since in many ways that's closer to the anticipated effects of the knock-out blow than was actual aerial warfare of the period. Perhaps surprisingly, there are a few such games, such as the Warplan: Dropshot/First Strike series and Fail Safe. Unfortunately I don't have any of these, though perhaps unsurprisingly I have been meaning to change that. These, of course, would be at a completely different scale to aerial warfare in the 1920s and 1930s, though that may not actually be too much of a problem at the strategic level.

It all depends on what aspects of the knock-out blow I want to simulate. I'll think through some of those choices in another post.

- There are some alternate history wargames out there, but in my experience they tend to either stick fairly closely to the real history, such as Case Green, or else tend to be fairly fantastic dieselpunk scenarios, Crimson Skies-style (or Aeronef for the steampunk crowd, and let's not forget the roleplaying equivalent, Forgotten Futures). I did find an interesting discussion on Interbellum about the wargaming potential of H. G. Wells's The Shape of Things to Come (1933), which is not too far off the mark; but that seems to be for miniature gaming. See also this, on the same blog. [↩]

One book, 2013

[Cross-posted at Society for Military History Blog.]

If I had to recommend one military history book I've read this year it would be Philip Sabin's Simulating War: Studying Conflict through Simulation Games (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2012). Admittedly, this is not your usual military history book. Sabin ranges at will from the 5th century BC to the present day, devotes twelve pages of its bibliography to games as well as providing the rules to eight games in the book itself, and talks about things that didn't happen more than those that didn't. The reason for all this is that Sabin argues, I think persuasively, that insights into historical warfighting can be gained through historical wargaming. In particular, he advocates the use of wargames in teaching military history, something he has much experience in and offers much advice about. Firstly, Sabin argues that what it is best to use what he terms manual wargames rather than computer wargames, that is played with dice and paper on a table-top (though there are in fact computer-assisted versions too). The advantage of this is that students can easily understand the rules, rather than have them hidden in a software black box. More importantly, they can also modify the rules, to experiment with increasing realism or playability, for example, or to alter what is being simulated. Even more importantly, they can design their own games, to reflect their research and understanding of a particular war, something Sabin has his own MA students do. Secondly, he advocates the use of what are called microgames with small maps and no more than twenty or so pieces per side, as opposed to the more complex wargames available commercially, which can have hundreds or even thousands of counters and very finely detailed maps. The main reason for this is that in his experience anything more complex than this is too hard to teach in a two-hour class. Also, given the need to make a game playable as well as gaps in our knowledge of the battle or campaign being simulated, Sabin suggests that it is better to focus on accurately representing key dynamics, such as the importance of suppressing fire in infantry combat, rather than trying to incorporate every last detail. Thirdly, and relatedly, for several of his courses Sabin uses nested simulations to represent warfare at different levels. So for the Second World War, he uses one game covering the war in Europe from 1940 to 1945, another focusing on the Eastern Front, a third at the operational level (depicting the Korsun pocket), and a fourth at the tactical level, gaming an assault by a British infantry battalion against German defences. This enables him to highlight the ways in which warfare looks different at different scales. There's much more in here, reflecting Sabin's years of teaching, playing and designing wargames; it's an essential book if you're interested in trying this at home (or in the classroom).

So if you had to recommend one military history book you've read this year, what would it be? What one book most impressed you, informed you, surprised you, moved you?

Note: I've changed the book featured here. I may discuss the reasons for this in a future post.

The sum of their fears

While archival research can be slim pickings, I suspect that this may not be such a problem for my Great War panics project, given that on my recent trip the UK I found some really good examples without even trying. The following is an excerpt from a letter dated 7 June 1915, sent to the navalist and journalist Arnold White by a member of the public (the first item in the list is a -- false, as far as I can tell -- claim that the same man had been captain of both HMS Bulwark and HMS Princess Irene and had left 15 minutes before each was sunk by internal explosions, and was court-martialled and shot):

Second, the last German Zeppelin raid [presumably 4 June 1915] has been very serious in loss of life at Tilbury, Gravesend, Greenwich Hospital, Enfield and elsewhere. The [objective] was Woolwich where Von Donop is [still] in charge. Engineers who meet him daily are astounded at the Government keeping him there!

Third, the 'guide' to the last raid is, as I have previously referred to, a motor cyclist with a side seat and a woman. This I have from a man who saw it flashing an upward light at the last raid with a Zeppelin following. I have seen the couple pass my house at Castlenau several times -- they go at great speed.

Fourth, I hear, again on good authority and from an Engineer who has frequently to meet von Donop, that the next Zeppelin raid in force will be made, (as they now know their ground) on Woolwich and that the German Navy will come out to meet our Navy, and the opportunity will be made for the German [transports] to slip out and attempt a landing at Southend. [Personally] I believe the S.E.Kent Coast will also be a base for their operations -- Ramsgate in particular -- they want waking up there -- Especially the Chief Constable -- its [sic] still a hotbed of spies.1

So Major-General Stanley Von Donop, Master-General of the Ordnance, is a suspicious character, apparently even more so since Woolwich Arsenal was the objective of the last Zeppelin raid, which caused serious loss of life. He may be connected with the couple in the motorcycle and sidecar who were seen guiding the Zeppelin. He is also apparently somehow involved in the next Zeppelin raid, also on Woolwich, which will be coordinated with a sortie by the German fleet and a landing by the German army at Southend in Essex. Also, spies or something in Kent. Of course, the spineless authorities are doing nothing about it. (White, at least, was paying attention: in 1917 he published The Hidden Hand detailing German infiltration and subversion of Britain.)

Just about none of this was true: if Von Donop, grandson of a German nobleman but son of a British admiral, was a German agent, he was never found out; spies did not go out at night to guide Zeppelins to their targets; nobody was killed in the air raid of 4 June 1915; the next Zeppelin attack wasn't on Woolwich but on Hull, and there was no German fleet sortie then, let alone a landing in Essex. In fact, this is an excellent example of the intersection and interaction of the three types of scares I am looking at: invasion, spies, air raids. These didn't exist in isolation, but could complement and reinforce each other, in a sum of the British people's fears.

More

I've been awarded a small grant by the University of New England to fund research into 'Popular perceptions of the German threat in Britain, 1914-1918'. I'm very fortunate to have received this and very grateful. The basic idea is this:

This project will investigate the British public's reaction to the threat of German attack during the First World War, including invasion, air raids, and espionage. Broadly speaking, the anticipation of such attacks before 1914 has received occasional attention over the last few decades. However, the way these fears actually developed during the war itself is less well understood. From scattered evidence it is known that they included trekking to safe areas, spontaneous organisation of civil defence measures such as the occupation of Tube stations as air raid shelters, and anti-German riots, but no comprehensive study has been carried out, with the recent and partial exception of invasion fears in south-east England in 1914. These fears are important for several reasons. Firstly, because they played a role in strengthening or weakening popular support for the war. Secondly, because they played a role in the retention in Britain of substantial military, naval and aerial forces which could have been deployed on the Western Front and elsewhere. Thirdly, because during the 1920s and 1930s, memories of air raids by Zeppelin and Gotha bombers led to an exaggerated fear of bombing which in turn had significant psychological, political and military consequences.

This is designed to be a standalone project (i.e. and an article), but it's also designed to support my longer-term mystery aircraft research by establishing a sort of baseline for the effect and extent of other forms of scares. How I (tentatively) plan do this is as follows:

- Using a combination of distant and close reading techniques, survey the British wartime press to identify periods when fear was likely at its highest, which will likely include the period after the fall of Antwerp, October 1914; the battlecruiser and Zeppelin raids in December 1914-January 1915, the first London air raids in May 1915, the height of the Zeppelin raids in the winter of 1915-6; the daylight Gotha raids in the summer of 1917; the night Gotha raids in the winter of 1918; and the German spring offensives of 1918. This can be done via the Internet using digitised newspaper archives such as the British Newspaper Archive and Gale NewsVault, which between them give good coverage of national and provincial daily newspapers.

- The core of the research will be undertaken in London:

I. 1 week research at the National Archives to examine the official understanding of public fears and responses to particular incidents such as riots and trekking.

II. 2 weeks at the Imperial War Museum to survey diaries from relevant places and periods to ascertain privately held and expressed reactions to the German threat.

III. 1 week in a provincial archive in a threatened area such as Hull or Norwich as a check of the predominant London bias of many sources, to gauge local government understanding of and responses to the German threat.- Analysis of data and followup research, if necessary.

This is significant for a number of reasons. First, it's the first time I've won any substantial research funding. Second, it will be the first time I've moved outside aviation history to any real degree (even if I will still be mostly doing aviation history). And third, while my last research trip to the UK may not have been completely successful, I will be going back for more.

Small moves

Now that I'm back home, it's time to sum up what my UK sojourn achieved. The short answer, at least in terms of my immediate research objectives, is that it yielded only mediocre results.

The ostensible purpose for the trip was to attend the Empire in Peril workshop at Queen Mary and to give a paper on the 1913 phantom airship scare. This I did, and I think it went well enough (though perhaps in future I should revert to actually reading a paper, rather than speaking to slides). It certainly helped that I was after Michael Paris (Central Lancashire), who set the scene with a discussion of early aerial warfare fiction, and Michael Matin (Warren Wilson), who used the phantom airship scare as a starting point to reflect upon invasion scare literature more generally. This capped off a stimulating two days of papers and discussions about, inter alia, inter-service debates regarding the possibility of invasion (Matthew Seligmann, Brunel; Richard Dunley, KCL), the representation of compulsory service in invasion scare fiction (Harry Wood, Liverpool), the Yellow Peril (Robert Brown, Birmimgham; Ailise Bulfin, Trinity College Dublin); and women writers on Germany (Richard Scully, UNE). A usefully discordant note was struck by Ian Hopper (Brandeis) who questioned just how seriously publishers, authors and readers took invasion scare novels: were they reflective of deeply held fears or simply trivial entertainments adapted to the political themes of the day? Perhaps the standout talk was the public lecture given by Nicholas Hiley (Kent), who reconstructed 'Vernon Kell's perfect nightmare', i.e. the German invasion of Britain as supported by the large number of spies and saboteurs believed to be lying in wait for Der Tag, as was fully expected at the outbreak of war by MI5, and hence prepared for -- but played down after the war in favour of the very different, and less impressive, threat posed by the handful of naval spies rounded up in the first days of the war by Kell's men. Apart from the papers themselves, of course, there was the usual networking: identifying a nucleus of researchers interested in broadly the same topic is a useful thing in itself, and may lead to future workshops, research and publications.

...continue reading