The road to war — IX

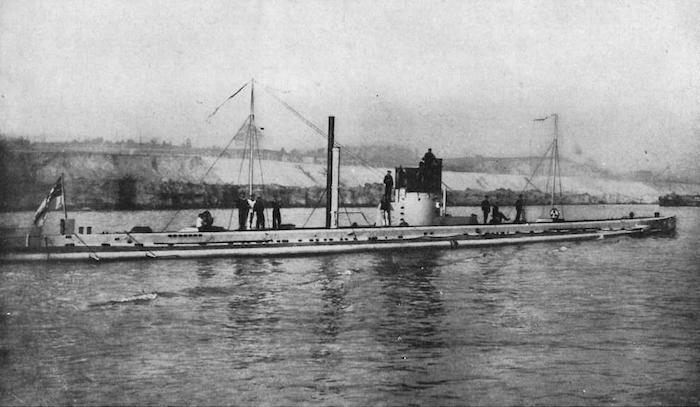

Today I made my ninth contribution to ABC New England’s Road to War series, talking about U-boats (AKA ‘the Zeppelins of the sea’) and their advantages and disadvantages in warfare. More specifically, I spoke about the German declaration on 4 February 1915 of unlimited submarine warfare in the seas around Britain, switching from their previous […]