Paris has, unfortunately, been in the news lately, which has made me think back to my visit in December 2013. Happier days. I never got around to posting any photos from that trip, so now seems like a good time to rectify that. But because you can find far more beautiful pictures of Parisian landmarks just about anywhere, I’ll just focus on airminded Paris. (With the exception of the Arc de Triomphe, above.)

I went to two aviation museums, the first of which, the Musée des Arts et Métiers in the 3rd arrondissement, is not actually an aviation museum as such but a technology museum. Within the walls (built in the 13th century as a monastery, though mostly rebuilt in the 18th century, with the museum itself dating to 1794) is a small but world-class collection of aeroplanes. For example, this is Clément Ader’s Avion III, a steam-powered and bat-winged aeroplane which failed to fly on 14 October 1897. Ader later claimed it had flown a hundred metres, but if so it’s hard to explain why the French army then discontinued funding.

A Blériot XI, but not just any Blériot XI — it’s the one that Louis Blériot used to become the first person to fly across the English Channel on 23 July 1909. It’s obviously no longer in a flyable state, unlike the one in the Shuttleworth Collection, and in fact it never flew again after its famous flight.

The Esnault-Pelterie REP 1, first flown in 1907, the first aeroplane to use a joystick for control (which unfortunately you can’t quite see here).

A Breguet RU1 from 1911 (or so). Not quite as historically significant as the preceding aircraft, although it did have an unusually high amount of metal in it for its day. Incidentally, just under its lower wing can be seen the Foucault pendulum (or at least the pedestal it swings over), which used to be the Foucault pendulum, the one used by Foucault in 1851 to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth (and the one from Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum, a key part of which is set in the museum). But in 2010 the cable snapped and the bob was damaged.

The other aviation museum I visited in Paris is indeed a proper aviation museum, the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace out at Le Bourget. Here’s an Antoinette VII, and behind it another Blériot (yawn), and underneath an Astra-Wright.

One of the cutest aircraft on display, a Demoiselle No. 21, c. 1909, one of the last of many contributions of Alberto Santos-Dumont to early aviation.

Le Bourget used to be Paris’s main international airport (it’s where Lindbergh landed in 1927) and the splendid art deco passenger hall is still preserved within the museum, more or less restored to its 1930s appearance. I say more or less because I rather doubt they parked Morane-Saulnier Type Gs in the concourse back then.

Also, this clock doesn’t quite seem period, and they haven’t tried to recreate the c. 1937 astrological and geographical artwork either. (Nice to see a clock for Melbourne, rather than say Sydney, though.)

Nevertheless it’s very pretty.

An elegant airport, for a more civilised age (or at least one with less need of Schiphol signage).

Back to the aircraft now. The First World War gallery was very well done (I must say it shades the RAF Museum’s new equivalent, although I understand that’s still a work in progress). This is a Voisin V pusher, an early-war bomber.

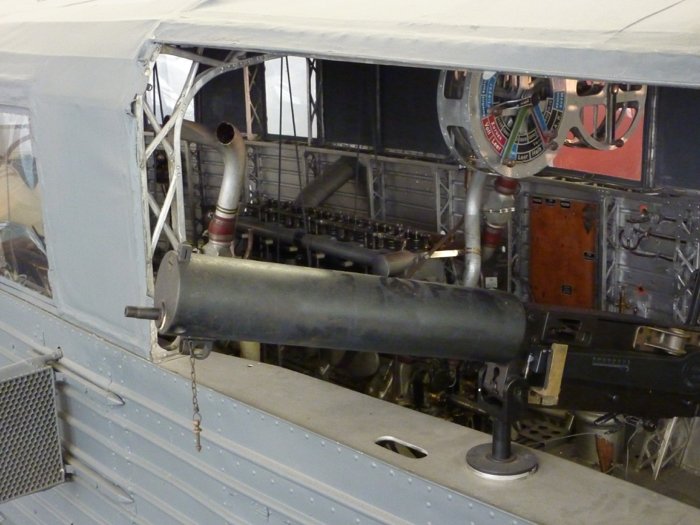

The rear control car of LZ113 (tactical number, not to be confused with production number LZ113), originally a military Zeppelin but transferred to the navy in August 1917, for which it flew 15 missions over the Baltic. It was given to France as war reparations in 1920 where it was used for structural testing.

The quadruple tail of a Caudron G4.

A SPAD VII, one of the war’s great fighter aircraft; the very one flown by one of the war’s great fighter pilots, Georges Guynemer.

A late-war Junkers D1; out of about 40 built this is the only survivor. It was the first all-metal (corrugated!) fighter to go into service (for the German navy), so it’s doubly significant.

On to the ‘espace’ part of the museum. This is a replica of France’s first satellite, Astérix (yes, named after the gallant Gaul), launched 26 November 1965 (and still up there). The French were only the third country to launch its own satellite using its own rocket, something they are justifiably proud of.

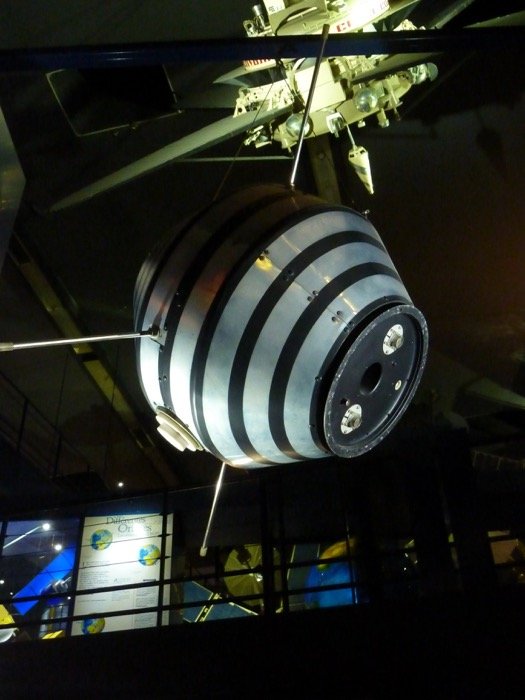

A label on the Soyuz T6 capsule, in which in 1982 Jean-Loup Chretien became the first French person in space, helpfully suggesting that rescuers should ‘open the hatch!’

A gloriously red Breguet 19 from the interwar hall. Designed as a light bomber, this particular example is actually a variant modified for long distance flights. Named Point d’Interrogation (i.e. ‘?’) it made the first heavier-than-air east-west crossing of the Atlantic, Le Bourget to New York, in September 1930. The stork on the fuselage is not to be confused with the stork on the fuselage of Guynemer’s SPAD above; there it’s a symbol of Escadrille 3, here it’s a symbol of Hispano-Suiza, the engine manufacturer. Seems unnecessarily confusing, though.

Many of the museum’s bigger aircraft are outside, but its the rockets which grab your attention. Here, Ariane 5 (first launch 1996).

And here, Ariane 1 (first launch 1979). They’re only mockups, but it was easy to imagine them lifting off all of a sudden –– though I would have preferred to be a bit further away in that case!

A SEPECAT Jaguar. SEPECAT was a one-off collaboration between the French Breguet (shortly Dassault) and the British BAC, and stands for Société Européenne de Production de l’avion Ecole de Combat et d’Appui Tactique; but ain’t nobody got time for that.

The First World War is understandably given more attention than the Second (though this difference was less marked in the military museum at Les Invalides, thanks to the Resistance and, in an odd way, Napoleon). But here’s a somewhat worn Heinkel 111 — except, of course, it’s not, although it does play one in the movies. It’s actually a Heinkel 111 derivative built in Spain after the war, the CASA 2.111.

This is definitely Second World War vintage, a rare Dewoitine D.520, the Armée de l’Air’s best fighter in 1940. It looks the part, too.

A Concorde…

… and a Concorde. Two Concordes. This one is the first prototype, the other is the second-last production number.

Something which is not very well represented in the Musée de l’air et de l’espace is the great French tradition of fugly aircraft. The only place where you get a sense of this is in this gallery, but then these are all experimental prototypes, so weird is normal.

This one is actually not very fugly, the SNCASO Trident, an interceptor from the 1950s which never went into production. Twin turbojets on the wings, rocket in the rear, Mach 1.6.

This is definitely bizarre. One of the world’s first ramjets, development of the Leduc 0.10 began in 1938 and remarkably continued right through the Vichy period until the first flight in 1947. Because ramjets don’t work at zero velocity, the 0.10 needed a carrier aircraft to get it up to speed. Where does the pilot sit? You may well ask. The pilot sits inside the ramjet itself, behind the spike; you can just make out the canopy, and there are portholes on the fuselage. At Mach 0.85 it must have been a very interesting way to fly.

The Hall de la Cocarde, or Hall of the Roundel. I didn’t even notice the massive roundel at the time! Too busy looking at the Ouragans, the Mystères, the Mirages…

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Ader thought he’d flown; a Sergeant Neute from the Engineers, who was there, thought Ader had flown; but the generals observing thought the plane had only skipped along the ground. And a steam-powered aircraft with no forward view for the pilot may not have been a basis for the future …

The 520 gets good press, and it was certainly more modern than its Maurine-Salnier rival, and liquid-cooled, compared with the Bloch, but a lack of engine power gains means that its thrust-to-weight ratio was in the same range, and the high wing loading was not overly desireable. The 520 could have been a world beater, but only had Hispano-Suiza been encouraged to design its engines for power rather than maintenance life cycle costs.

In that way, it’s sort of an object lesson to governments facing demand deficits that decide to go cheap on spending against downside policy outcomes. I know, I know, the enthusiasts always think defence expenditures are too low. Point is, in the France of 1937–9, they were.

Next time you’re there, try and take in La Maison du Livre Aviation at 75 boulevard Malesherbes, 75008 Paris for aviation books and magazines in many languages.

The First World War gallery was very well done

I thought their presentation in this gallery was nearly as good as the Aviation Heritage Centre in Omaka, Blenheim NZ. Of course, Paris has a higher quality of underlying airframes!

Ian:

Yes, as so often it depends on how ‘flight’ is defined (your own blog is a good source for Neute’s account!). But apparently Ader only claimed to have flown much later (certainly by 1910). Richard Hallion (Taking Flight: Inventing the Aerial Age, from Antiquity Through the First World War, p. 134) calls the test an ‘unambiguous failure’, but on the other hand notes that the official report did in fact recommend continued trials. He suggests that the War Ministry had more important things to worry about at the time, then being embroiled in the Dreyfus affair; that doesn’t quite seem plausible to me, but it could well be the case that non-technical reasons were involved. (You’re right that steam power was not exactly the way of the future, but we know that; they didn’t; and while having no forward view sounds like a bad idea, Lindbergh managed to fly non-stop across the Atlantic without one. Avion III was a prototype; if the will had been there then these problems could have been fixed.)

PS I liked your post on ugly French aircraft, also an interest of mine.

Erik:

The D.520 is anyway a red herring — the important point is that if France had simply built more D.550s, it wouldn’t have lost in 1940. As I’m sure you well know.

Nick:

Thanks! Hopefully it will still be there by the next time I visit — on past form it could be a while.

ErrolC:

Not every aviation museum can have a Peter Jackson to help out, I suppose!

Well, more Richard Taylor than PJ, but yes :-)

I was listening to this great extended audio tour of The Vintage Aviator construction facilities on Radio NZ.

http://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/ourchangingworld/audio/20164204/recreating-vintage-airplanes-long-version

They mentioned the access that TVA got to the Australian War Memorial’s Albatros D.Va to help to create new plans. I assume that part of the deal for access was the work that TVA and Weta Digital did on the ‘Over The Front’ exhibition.

http://www.theaerodrome.com/forum/showthread.php?t=38756

One day I’ll get back to the AWM, maybe even Omaka!