So, to conclude my survey of the career of Stanley Baldwin's phrase 'the bomber will always get through' in the British press (or at least in the British Newspaper Archive), here's how it fared during the Second World War.

...continue reading

So, to conclude my survey of the career of Stanley Baldwin's phrase 'the bomber will always get through' in the British press (or at least in the British Newspaper Archive), here's how it fared during the Second World War.

...continue reading

I showed in an earlier post that scepticism of Baldwin's dictum that 'the bomber will always get through' begins to appear in the British Newspaper Archive (BNA) in 1937, if only in a very small way. In 1938, the majority opinion still takes it to be axiomatic. For example, town alderman W. A. Miller, attacked the lack of information available about Plymouth City Council air raid precautions (ARP) planning:

'It is pure pretence to say you can offer any defence against the bomb,' he said. 'The bomber will always get through. When the things happen for which these precautions are intended, anarchy will not be in it.'1

W.V. of Belfast began a letter to the editor of the Northern Whig by stating that

'The bomber will always get through,' bombs will be dropped, and many people killed despite air raid precautions. Against high explosives no protection is possible.2

In July, George Lansbury, pacifist and former leader of the Labour Party, gave a widely-publicised speech in which he referred to 'the cold fact attested by military and scientific authorities [...] the bomber must always get through'.3

But this kind of discussion drops off later in the year. The phrase 'the bomber will always get through' doesn't appear at all in BNA in September or October, the months when the Sudeten (or Munich) crisis and the threat of a knock-out blow from the air dominated the news.

...continue reading

Today, a Trove API upgrade, or to be more precise, the decomissioning of the old API, briefly broke Trove Air Bot (and all the other Trove bots). Fortunately Tim Sherratt worked out a solution, and Trove Air Bot is now back in action with all new code, which (with slightly more useful comments) can be found here. Probably nobody noticed anything other than me -- except for when the bot blasted out a few dozen tweets in the space of a few minutes while I was editing the project! Sorry about that...

Bonus! The bot still does basically the same thing as originally, and its tweets look much the same; but it now uses a wider range of keywords, rather than just one. Whereas version 1 searched for newspaper articles containing 'aviation' (or variants, such as 'aviator'), it now randomly searches on one of the following:

aeronautics

aeroplane

aircraft

airplane

airship

aviation

balloon

helicopter

I could have added others, particularly for the aircraft. An obvious one is 'plane', but this gets hundreds of thousands of results every decade in the second half of the 19th century, which will be nothing to do with aviation. (This could be a problem with 'balloon', too.) Conversely I could have included words like 'Zeppelin' or 'autogyro', but that becomes a question of diminishing returns (where do you stop? 'ornithopter'? 'ekranoplan'?? 'vimana'???), and given that the selection of keywords isn't weighted in any way I don't want the results to be dominated by a weird, long tail. The above set of keywords should capture a high proportion of the kind of articles I'm looking for, while remaining reasonably coherent. Hopefully!

After the drama of 1934, 'the bomber will always get through' appears less frequently in the British Newspaper Archive (BNA) in 1935 (though still at about twice the level than in 1932 or 1933). But it is still mostly being used in a very political way. This is not surprising, with the general election contested in November to a significant extent on issues of collective security and national defence. In fact, it was most often used by the Labour Party to argue against the National Government's rearmament policy -- which must have irritated Stanley Baldwin, now prime minister again, no end.

...continue reading

Stanley Baldwin's 'the bomber will always get through' speech was not widely quoted in the British press in the 1930s. But when it was quoted, how was it used? To determine this, I'm going to do a closer read through of the British Newspaper Archive (BNA).

...continue reading

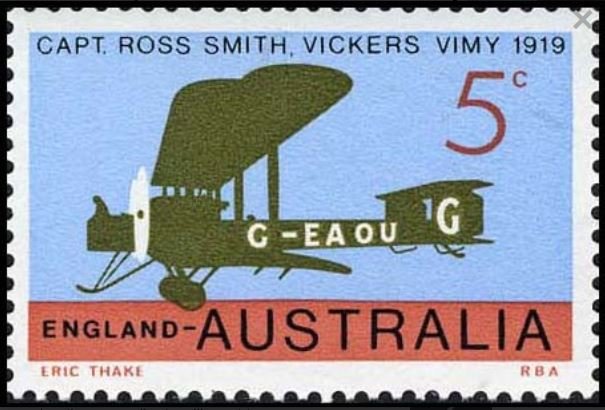

Michael Molkentin. Anzac and Aviator: The Remarkable Story of Sir Ross Smith and the 1919 England to Australia Air Race. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2019.

[Disclaimer: Michael is a friend of mine. But I wouldn't have agreed to review his book if I wasn't confident, based on everything else that he has published, that it was going to be excellent. And I was right.]

Anzac and Aviator is a new biography of Ross Smith, the first Australian aviation pioneer to find global fame.1 This fame rested largely on just one flight in 1919, but it was a truly epic one: the first flight from Britain to Australia. At around 18,000 km, it was the longest to date (albeit carried out in stages, unavoidably). Despite being accompanied by his older brother (and fellow pilot), Keith, Ross -- it's hard to avoid using first names in this review! -- was the driving force behind the flight. With the centenary of the flight this December almost upon us, this biography is timely.

...continue reading

My article, 'The meaning of Hendon: the Royal Air Force Display, aerial theatre and the technological sublime, 1920–37', has been accepted for publication in Historical Research (the journal of the Institute of Historical Research). I'm not sure when it will be published yet, and I can't self-archive the post-peer-reviewed version until 24 months after publication. The submitted, pre-peer-reviewed version I can self-archive now, however. There are some substantial differences between the two, mainly in the historiographical discussion in the introduction, as well as some errors I caught after submission, but the two versions are close enough that I'm happy to post the submitted version now -- and here it is. This is the abstract:

The annual Royal Air Force Display at Hendon was a hugely popular form of aerial theatre, with attendance peaking at 195,000. Most discussions of Hendon have understood it as 'a manifestation of popular imperialism', focusing on the climactic set-pieces which portrayed the bombing of a Middle Eastern village or desert fortress. However, scenarios of this kind were a small minority of Hendon’s set-pieces: most depicted warfare against other industrialised states. Hendon should rather be seen as an attempt to persuade spectators that future wars could be won through the use of airpower rather than large armies or expensive navies.

There are three things I wanted to do with this article, which to some extent are independent of each other. The first is to push against the prevailing historiographical understanding of the RAF Display as primarily imperialist and racist propaganda. This is the one thing that everyone 'knows' about Hendon, and I've written that myself, but it's wrong. As noted in the abstract, my case here is primarily numerical and chronological: only a quarter of the set-pieces were 'imperial', none of them after 1930. This doesn't necessarily invalidate discussions of those specific set-pieces as imperialist and racist propaganda, because they were, but we need to recognise that they were not what Hendon was mainly about.

So the second thing I wanted to do was to offer an alternative reading of Hendon, and that is as 'one long argument for airpower supremacy' (to quote myself). Most of the set-pieces involved industrial (and so presumably European) targets: factories, power stations, and so on. (See my posts on the Hendon set-pieces.) These were targets that only the RAF could attack. Other set-piece targets, such as siege guns and merchant cruisers, could have provided an opportunity to portrary cooperation with the Army and the Navy, but didn't (a point I could have made more strongly in the article). So Hendon was 'a cultural projection of what David Edgerton terms liberal militarism' (to quote myself again!)

The third and final thing I wanted to do with this article was to showcase the usefulness of aerial theatre. I've already given the concept an outing in my article on 'The militarisation of aerial theatre', but Hendon was of course the biggest and best air display in interwar Britain and so it's the ideal case study -- if the concept has any validity at all! I've also tried to link aerial theatre to the concept of the technological sublime; again, I'll be interested to see what others make of this.

This is not my final word on Hendon, by any means, but it's a good start.

The man: Stanley Baldwin. The place: the House of Commons. The date: 10 November 1932. The quote:

I think it is well also for the man in the street to realize that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed, whatever people may tell him. The bomber will always get through [...] The only defence is in offence, which means that you have got to kill more women and children more quickly than the enemy if you want to save yourselves.1

I use this quotation all the time in my scholarly writing: in my book, in four peer-reviewed articles, and in two forthcoming publications (as well as a bunch of times on Airminded). It's just such a perfect encapsulation of the knock-out blow theory, and from such a prominent British politician too, that I find it impossible to resist. (To be fair, I'm hardly alone.) The only competitor for my affections is by B. H. Liddell Hart:

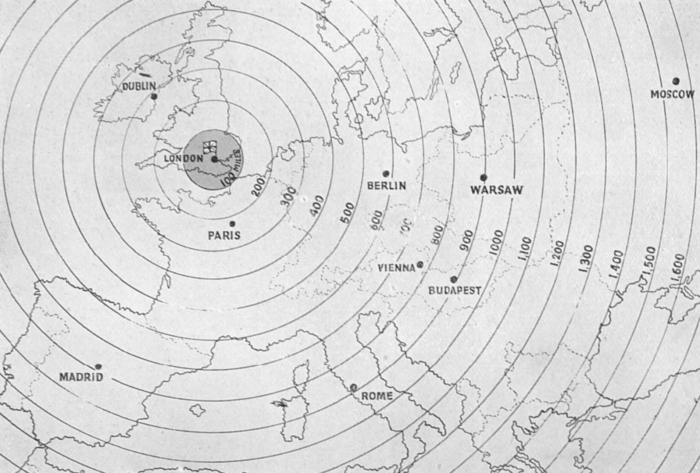

Imagine for a moment London, Manchester, Birmingham, and half a dozen other great centres simultaneously attacked, the business localities and Fleet Street wrecked, Whitehall a heap of ruins, the slum districts maddened into the impulse to break loose and maraud, the railways cut, factories destroyed. Would not the general will to resist vanish, and what use would be the still determined fraction of the nation, without organization and central direction?2

Which is more vivid, but not as succinct, and doesn't get across that the consequence of the apparent impossibility of air defence is the logic of mutually assured destruction. And so I always come back to Baldwin. I have used the Liddell Hart quote in my book and in one forthcoming publication, but always as well as 'the bomber will always get through', never instead of it. Baldwin is just too quotable.

...continue reading

Swastika Night was written by Katharine Burdekin under the pseudonym Murray Constantine. It's a dystopian novel in which Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan have conquered the world and divided it between them. Nothing so original in that, you might think -- except that Swastika Night was published in June 1937, before the invasion of Poland and even before the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. So it's not, strictly speaking, an alternate history, but an uncanny form of one.

...continue reading

From the climactic set-piece at the 1927 RAF Display at Hendon, the destruction of an 'Eastern village' by Fairey Foxes -- in GIF form: