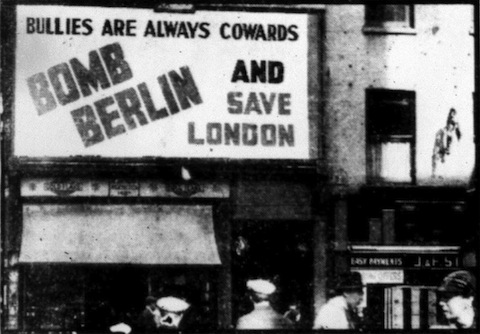

Bomb Berlin and…

This photo appeared on the front page of the Sunday Express on 6 October 1940, a month into the Blitz. A caption explained, or rather asked: WHO PUT UP THIS POSTER? This mystery poster has appeared in the streets of London. It is about six feet high and ten or twelve feet across, and bears […]