Gospel airships, heroic hearts and holy scriptures

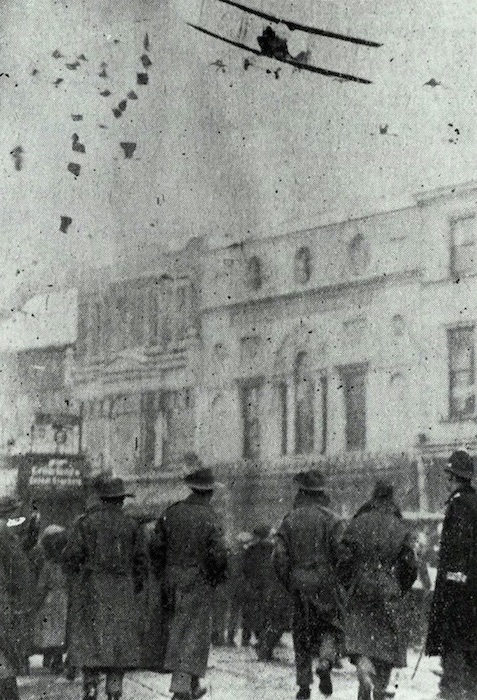

Proselytisers are famously early adopters of communications technology (see: the Gutenberg Bible). It shouldn’t be surprising that missionaries were intrigued by the development of aviation: a Baptist minister, Reverend F. W. Boreham, even claimed that It was with a view to winging the Gospel to the uttermost ends of the eaxth that the first airman […]