Anxious nation? — III

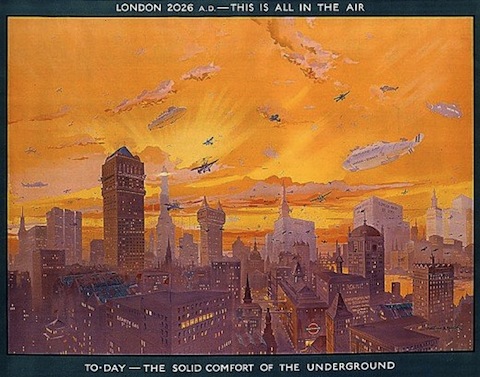

Aircraft don’t have to be military to be a threat to the nation. The ability to simply fly over frontiers makes them attractive to anyone who wants for some reason to enter a country without observing the legal usual formalities — smugglers, for example. Or at least, that seems to have been a widely-held belief […]