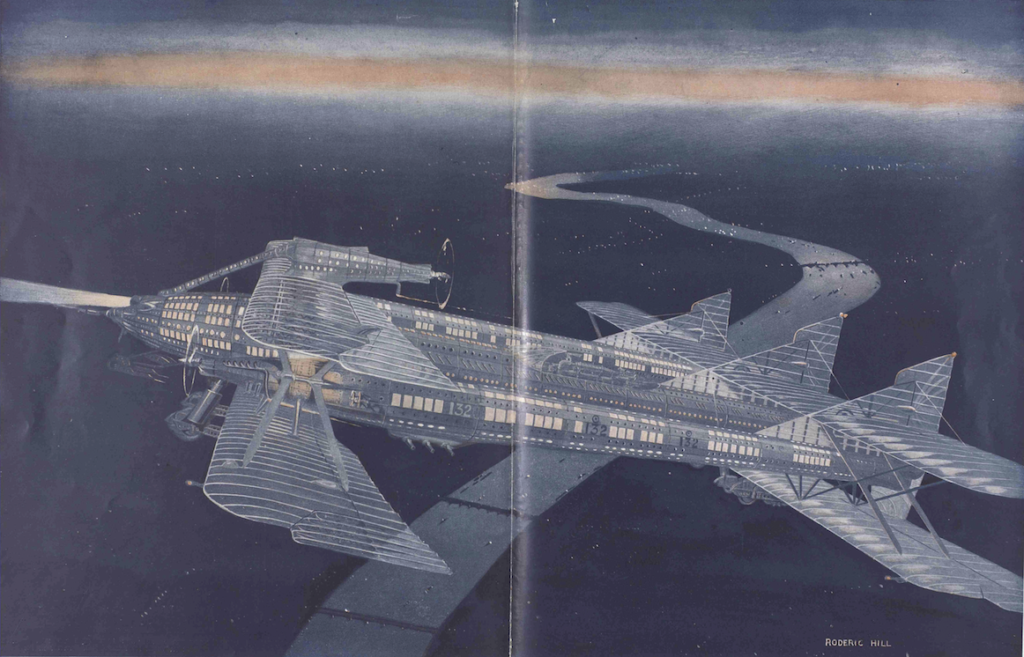

Modern wonders — I

For nearly four years from May 1937, Modern Wonder (Modern World from March 1940) was a British weekly magazine, priced at 2d. and aimed at, presumably, boys and young men who were interested in high technology, big machines and vehicles that go really, really fast — sometimes fantastical, but mostly real, if on or near […]