Australia and the airship — III

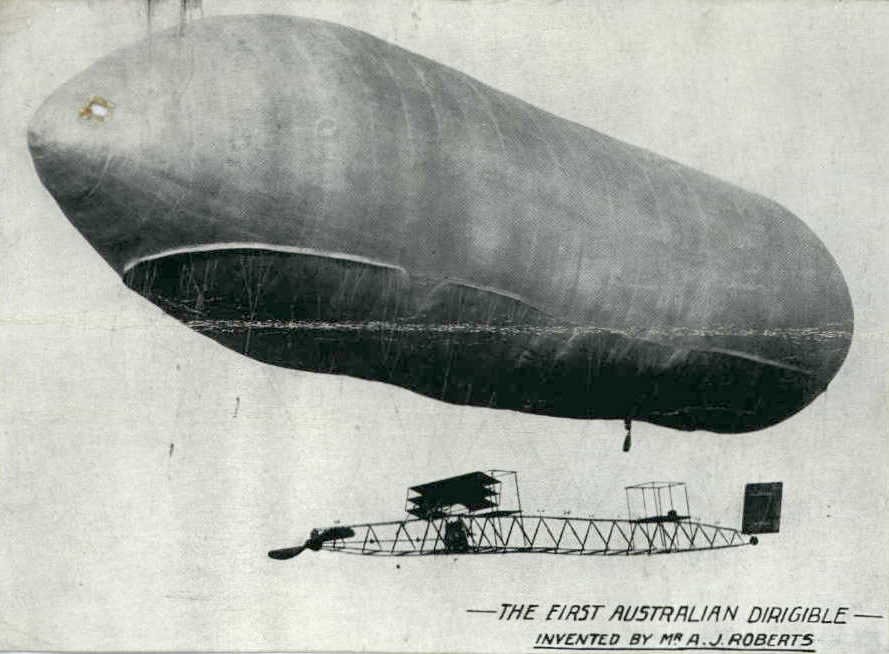

I ended the previous post in this series with the tease: In a final post, I will discuss what [Alban] Roberts called his airship, and what it might mean. That was over two months ago! I think it’s time to finally reveal the answer to this question. Errol Martyn, who has written what must be […]