A sister to assist ‘er

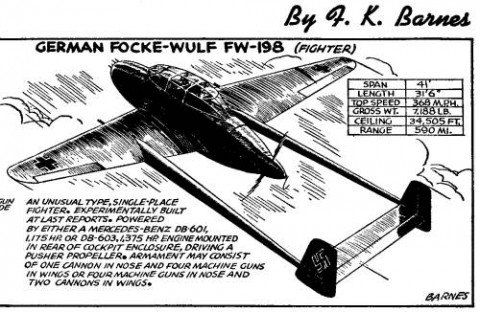

At the end of October 1940, while the British and German air forces were nightly striking at each other’s cities, Captain Norman Macmillan (a decorated RFC veteran and former head of the National League of Airmen) argued in Flight that Britain’s greatest need was for the development of a bomber which was possessed great speed […]