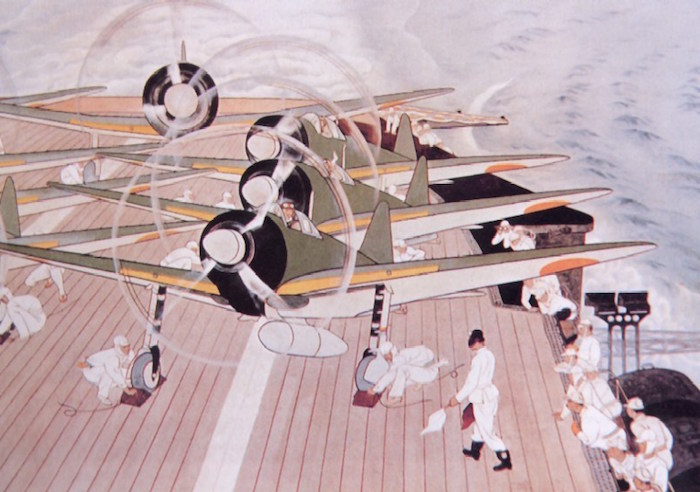

Mossies over Brissie

The State Library of Queensland identifies this image as ‘R.A.A.F. Mosquito bombers, ca. 1945′; I suspect it’s from a RAAF march and flypast put on for the Third Victory Loan in the centre of Brisbane on 6 April 1945. On that occasion, according to the Courier-Mail, The veteran Lancaster bomber ‘G. for George,’ will lead […]