I've noted that for the past two days two major London papers -- The Times and the Daily Mail -- have not led with the bombing of the city. I don't have today's Mail to hand, but it's the same for The Times today ('Fresh R.A.F. blow at Berlin', etc). But here is a provincial newspaper (albeit one with national influence), the Manchester Guardian, concentrating almost exclusively on the pounding the capital is receiving (5). I'm not sure what to make of this, or indeed whether to make anything of it all. Is it a liberal vs conservative difference (let's think about the wounded rather than focus on revenge) or a regional vs metropolitan one (Londoners don't need to be told what they are experiencing)? Or just small number statistics?

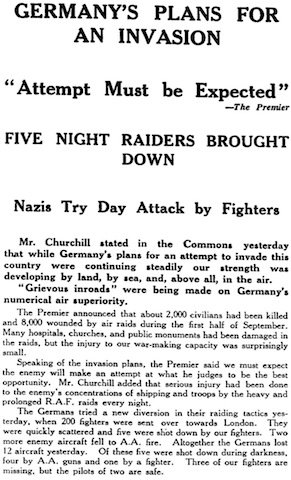

Anyway, London has now had four nights of 'indiscriminate' attacks ('the enemy has now thrown off all pretence of confining himself to military targets'), last night's still ongoing as the Guardian went to press.

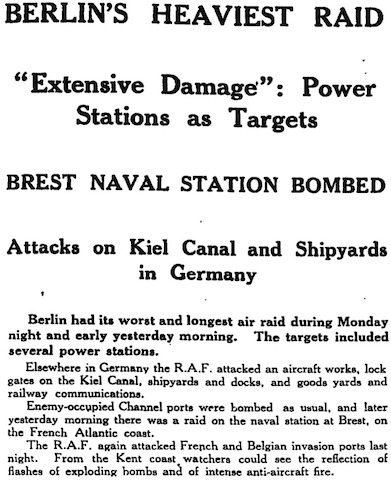

During the nine-hour on Monday night bombs were scattered at random over London. Fires were started near St. Paul's and St. Mary-le-Bow, and only the tireless work of hundreds of firemen saved these famous buildings. Bombs fell on a maternity hospital, a children's hospital, a nurses' home, a Poor Law institution for the aged, and workmen's cottages.

The casualties in the Monday raids are not yet known. Those for Sunday night's ten-hour raid amounted to 286 killed and about 1,400 seriously wounded.

The German press is now openly describing the bombing of London as a reprisal. BZ am Mittag said:

If London wishes to taste the full extent the fate of Warsaw and Rotterdam let the Churchill clique continue to send their pirates by night into Germany.

Germany has also thrown a new bomber into the fight, a 'modernised version' of the Dornier 215, a 'fast, long-distance bomber monoplane'. It is faster than the old Do 215 and has an extra gun turret, and formed the bulk of the German bomber force on Monday night. About three to five hundred bombers are being used in the 'attacks on London and other British cities' (and it is not just the capital which is being attacked: page 3 features some photos of 'Air-raid damage in the North-West', though some of it is described as only 'slight').

In an article called 'Sheltered life', M.R.H. (a woman, I think) writes of the absurdity of the air war:

Time after time [...] one overhears, in shops and streets and houses women saying to each other, some wearily, some bitterly, some wonderingly, "It's a silly game." Sometimes they add, "It doesn't make sense, all of us going into holes and shelters because a few men have been given bombs to play with."

M.R.H. finds hope in the very fact that people feel that, by virtue of actually experiencing them, they have permission to cut such great events down to size:

A great many, ignorant of social and historical forces and convinced of the impotence of the ordinary person to influence these, have in every generation lamented over what the world was coming to; now that they are all able to see and hear what it has come to, and discover with surprise that they themselves can diagnose the essential silliness of the catastrophe, it can seem that the outcome of a sense of individual power to shape our common ends may accompany a new realisation that the making of history is a job for common people who have ceased to be an indifferent majority indefinitely content to play "Follow my leader."

Such grand dreams of people power are very far from the mind of a northern clergyman writing to the editor as Shelter Marshal (8), reflecting his volunteer ARP job:

On Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays numbers of drunken men and women, as well as lads, stagger in and out of shelters. Fights, quarrels, bad language, the deliberate damaging of sandbags are the result. Men and women stupified with drink insist on leaving the shelters, often to collapse outside, sometimes injuring themselves so severely that police, A.R.P. wardens, and shelter marshals have to render first aid in the open and expose themselves to unnecessary danger.

Though Shelter Marshal does have some reforms in mind himself:

Unless the Government is prepared for a drastic limitation of drinking hours, as well as for the imposition of much more severe penalties, the only remedy seems to be that the police should have the power to eject drunken people from shelters and the shelter marshals authority to exclude them.

It might be tempting to write him off as a wowser, but he has a point: if drunken behaviour is disturbing the equanimity -- and perhaps the morale -- of shelterers, then it needs to be minimised. Yet surely shelters are for all, not just the sober, and just because some people are having fun -- or drowning sorrows -- on a weekend in wartime, does this mean they are not entitled to what safety there is to be found?

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Alan Allport

I'm not sure what to make of this

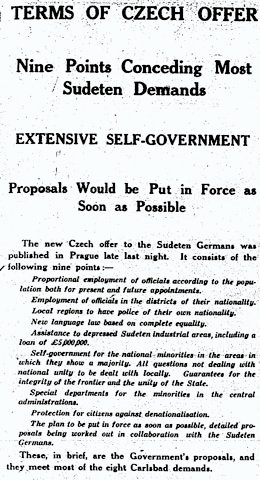

I expect what you're seeing is the lack of a single agreed narrative about the course of a battle that was still taking place. Because of the way the story of 1940 has been told by historians, we take for granted the importance of September 7 as a watershed moment - but clearly it didn't seem that way for everyone at the time. Indeed, one of the things that's been most interesting about your series so far has been the sense of incremental change: the campaign against Londoners was already taking place before the great raid of the 7th, and even after the formal start of the daylight Blitz this didn't necessarily seem the most important development in the war.

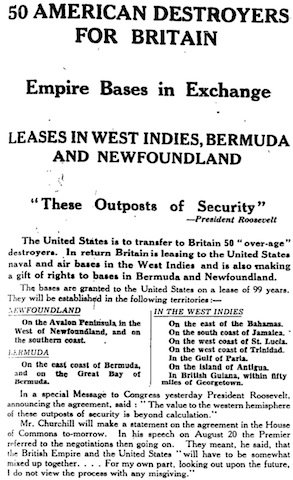

I'm reminded also of Churchill's 'Few' speech, which is remembered now for a single unrepresentative sentence. Churchill actually had very little to say about Fighter Command that day, and was far more interested in extolling the virtues of the Bomber Command offensive, Anglo-American relations, the war in Egypt, etc. After all, the air war over southeast England still seemed a preliminary skirmish before the apocalyptic invasion and land battle ...

Brett Holman

Post authorThe only reason why I hesitate is because I am using a small set of sources here. (We do have the 'popular WWII newspapers' on microfilm at the uni library but alas, I've had no time to look at them.) But the diversity of the contemporary narrative is certainly something I wanted to show, so I'm glad that's coming through. One of the things which had struck me previously was this incremental change you note; we speak now of the 'Battle of Britain' and 'the Blitz' as linked-but-different, and invasion is there too but it didn't happen so we can put that in the 'what-if' category. But it wasn't so clear cut at the time. But one thing I hadn't quite realised was the way in which newspaper readers, at least, were being constantly told how powerfully and precisely that the RAF had been hitting Germany for months now. It's one thing to present Londoners as stoically withstanding punishment, but it probably helped them to do so to think that Germany was having to take it too.

On 'the Few', indeed! And if you read that passage closely that phrase really refers to all 'British airmen', not just fighter pilots:

He does immediately go on to mention fighter pilots explicitly:

but note that semicolon -- here's the rest of that sentence:

So the Few that are remembered today are really only a few of the Few!

JDK

Very interesting contextualisation of 'the few'.

It is a pity that "by the highest navigational skill, aim their attacks" is complete rubbish, as is "with deliberate careful discrimination".

Sadly the "under the heaviest fire, often with serious loss" isn't.

This is no criticism of the men of Bomber Command, but reflection on the technical, training and equipment standards of Bomber Command of the 1930-40 period. (Had Fighter Command been so poorly served by their equipment, system and training in 1940...) Churchill may have believed his statements were mostly true, but then in 1941 there was Butt.

Neil Datson

The emphasis on the RAF bashing Germany is interesting. Again, much at odds with the subsequent popular mythologising, in which bombing is always portrayed as something that was done to the British by the Germans before the British really retaliated.

I have no doubt whatsoever that Churchill - however much he may have privately doubted Bomber Command's ability to hit high value targets - would never, ever have publicly suggested that its accuracy could possibly be less than A1.

Erik Lund

Actually, the RAF had a pretty intensive navigational training programme prewar. (And an arrangement with the University of Southampton, which offered a B. Sc. in navigation.)

Unfortunately, most pilots didn't go through it, because there weren't the resources to give everyone 20 weeks in a trainer. Graduates of the full course, offered as part of the School of Naval Cooperation's portfolio, were supposed to train fellow pilots at squadron level. In any event, I'd like to see a breakout of the squadrons the graduates were sent to, because no-one ever complains about Coastal Command's navigation....

What it all really points to is the limits of celestial and dead-reckoning navigation --in the immediate postwar generation of aircraft!-- and the need for a technological solution. Radio aids aside, that implies (to the extent that there is any one single technological fix) the Air Position Indicator, upon which the boffins at Farnborough are hard at work this morning. It will go into service early in 1943. The Germans are sowing the wind...blah blah blah.

JDK

Actually, prewar, at night, the RAF mainly managed to find mountains to scatter aircraft and crews on (see HP Heyford debacles) and anything with a nice big coastline or river.

'Inadequate' is a very accurate description, including the training exacerbated by the status of navigation in the RAF.

Gavin

I'm surprised and fascinated by how far the British press and public over-estimated Bomber Command in 1940. It's hard to see any logical reason why they should have thought that British bombers must be doing so much better than German bombers. From what we've seen so far it often seems to be presented in terms of morality and racial stereotypes: our decent chaps only bomb carefully selected military targets, but those beastly Huns just drop their bombs at random.

But this false belief does seem to have been good for civilian morale. I used to think that the "it was necessary to keep up morale" argument was a poor excuse for strategic bombing of Germany when it wasn't have much strategic or economic impact, but it looks like I was wrong.

JDK

This exercise of 'post blogging' certainly throws up stuff you'd not expect, doesn't it?

As per Brett's thesis, we tend to forget that pre-war it was all about the bombers and the emphasis on fighters since then is anachronistic, as we are seeing in Brett's posts here. The pre-war bomber-theory we can easily forget carried right into the war on all sides, and it's only with hindsight we understand they were rarely anything like the knockout blow that was so widely believed in, supported and worked for.

As you've touched on Gavin, it does illuminate the differences between our contemporary thinking and theirs.

As to the differentiation of ability and behaviour of 'our' guys versus 'theirs' it's obviously critical for historians to achieve a detachment from such propaganda-driven evaluation, but equally it mustn't be forgotten it's essentially an absolute - running down the enemy while overstating one's own claims seems - from memory and current events - to be standard behaviour.

Brett Holman

Post authorGavin:

Yes, the way in which the press kept pushing the bomber offensive does point to its perceived importance for morale. And it's understandable: no matter how well Fighter Command was doing, people living under the bombs had to have some belief that Britain was able to hit back and some hope that the war might end. The other question is, how far did ordinary people believe it?

JDK:

I think the pre-war bombermindedness is a hangover here, but I'm also aware of my own biases in selecting material here -- there are a lot of accounts of air-to-air combat that I don't quote (whether because I've covered it before or because I want to talk about bombers). Also, remember AVM Brooke-Popham's complaint about there being so many Spitfire funds and no Stirling funds -- that does point to a genuine popularity for the fighters.

Pingback:

Airminded · Wednesday, 18 September 1940