The Prime Minister gave a speech on the war situation to the House of Commons yesterday, which I'll come back to. The Manchester Guardian has a lot on the air war, of course (5). A big wave of enemy raiders, consisting of 'more than 200 Messerschmitt and Heinkel fighters' was broken up over Kent yesterday afternoon, getting no farther than Maidstone. Losses were small on both sides, however (possibly due to the heavy clouds and the '100-mile-an-hour gale' they fought in): seven German aeroplanes were shot down, and three British. Unusually, the defenders' record was nearly as good at night: anti-aircraft guns accounted for four enemy aircraft before midnight, and fighters one. The Luftwaffe dropped bombs central London, including the West End ('There was considerable aerial activity near Green Park'), and also on 'a South-East England village':

One dropped in a roadway, making a crater and causing considerable damage to houses and a number of casualties, some of them fatal. A couple and their four children had a remarkable escape when their house collapsed and they were buried in the wreckage.

So it's not just the big cities which are having to 'take it'.

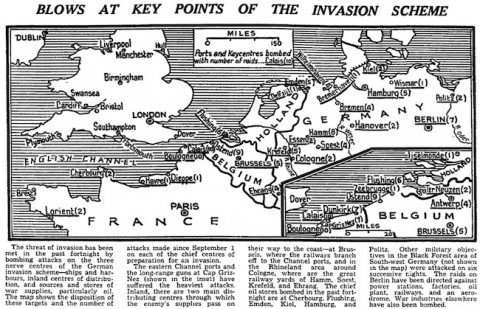

And there's the 'harrassing bombing action' against the German invasion forces assembling on the Continent (and the gale helped to disrupt them too), which the above map shows. An article from the Air Ministry News Service highlights the work of Coastal Command yesterday -- possibly because the bad weather precluded any Bomber Command raids (or am I just being cynical?)

These operations were supplementary to routine anti-submarine and convoy escort patrols, on which the aircraft flew 15,000 miles in a few hours, notwithstanding general bad weather.

To-day Coastal Command aircraft gave escort to many large convoys of merchant vessels, and there was not a single enemy attempt at molestation by air or by sea.

Not that this meant there was no action: one Coastal Command aircraft attempted to attack a convoy off Zeebrugge, but was fended off by three He 113s ('the new German fighters'). It then attacked barges in Zeebrugge harbour itself; it encountered heavy AA fire and the Heinkels came for it again but 'the raider had now completed its mission and made out to sea'.

The first leading article today discusses Churchill's speech on the war situation, covering 'the joint German-Italian effort against this country, here and in the Mediterranean' (4):

Here the indiscriminate bombing of London and the long battle with the R.A.F. are the preliminary to an attempt at invasion which Mr. Churchill believes the enemy will make "at what he judges to be the best opportunity." [...] No one ever attached more importance than Hitler to the principle of demoralising an enemy before striking at him; if he thinks that he has gained substantial successes over the mind of his enemy he will then look for the right wind and tide and light to fix the day.

Italy is advancing against Egypt, though it may have missed its chance there. Still, 'the two attacks go strictly together', with the aim of doing 'all they can to create new troubles for us'. Creating strain and confusion is indeed the key to German strategy.

By bombing London she aims at cutting off supplies, dislocating life and shaking the individual nerve, even (if her newspapers are to be believed) at driving the population out into the countryside -- a success that she has had elsewhere but will not have with us -- and at diminishing the military production of the country. The comparison is rough, but Hitler is trying to do in London as a prelude to invasion what, by bombing, parachutists, and troop carriers, he succeeded in doing at Rotterdam and the Hague as a support to the attack of his army from the east.

This strategy is not working: the damage done to production has been 'surprisingly small', Churchill said. German bombing by night is inaccurate and at day 'they risk meeting the R.A.F.'

With practice and day-time reconnaissance they may improve, but at present they are far from the standards reached by our own bombers. All told, Mr. Churchill could sum up that we can regard the air struggle "with sober but increasing confidence."

Churchill also talked about civilian welfare in the raids. The Guardian thinks that there needs to be more central control here:

Many different authorities are involved, and there ought to be some reconciling and directing force that can take in a complex situation as it develops day by day and take the necessary measures [...] with speed and efficiency.

All 'the great towns and industrial centres' should look at London's experience and revise their own ARP plans.

There may or may not have been excuse for whatever was inadequate in London's preparations. There will be no excuse in future for inadequacy there or elsewhere.

I'll close with an effective and quite moving 'open apology to children' on page 3:

Wake up children. I'm sorry -- you are terribly sleepy, I know, but the sirens are going. Come along, do try to waken. No, dear,, don't huddle down again. You really must get up and hurry downstairs. Lift your head. We are taking the pillow with us, and the eiderdown. Here are your slippers and gowns -- never mind the sleeves; you can get into your siren suits and your socks in the cellar. Yes, you gas masks are already down. Now wait for me; you are much too unsteady to rush down yourselves.

The heart of the piece is here:

There. All settled and cosy and nearly asleep again! I'll put out the light. Good night. Yes, I'm going to listen for a while and you can forget about the air raid.

Fortunately you can forget. You have forgotten even now, fast asleep in deck-chairs in a windowless cellar, in utter darkness. Your acceptance of all this shames us. You are not even frightened, because you still, strangely enough, trust grown-up people to provide you with the security you have always known to be your right to demand and their privilege to give; and it never occurs to you to challenge us to declare which of our failings have upset your ordered world or to say what part we have had in letting such things happen.

The author is M.R.H., who I also quoted last week. I wish I knew who she was.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

JDK

Ah, those 'Heinkel fighters'. I wonder what they really were? The most probable misidentification is 109s, but there is a theory that they were Hurricanes in friendly fire incidents.

There's definitely something to be written on misidentifications, and what was behind them, not just the propaganda but the psychology.

The differention between Blenheims and Ju 88s by R. A. Saville-Sneath mentioned on the 16th was a problem to pilots as well as civilians and was used in the well-founded TV series Piece of Cake based on the infamous real Battle of Barking Creek much earlier. (The Creek case was Spitfires on Hurricanes.)

Later we were to see RAF pilots being told that the new Fw 190s were actually second-hand ex-French Curtiss 75 Hawks. We've already seen here the Messerschmitt 'Jaguar'. Recently another discussion brought to light a USAAF claim in the late war of a 'Fw 290', clearly differentiating it (for what reason we don't know) from a Fw 190.

Pingback:

Airminded · Friday, 20 September 1940

Brett Holman

Post authorI see the misidentifications as a lot like the phantom airships, actually. You've got pilots and intelligence officers primed to be constantly on the lookout for new threats, worried that the enemy would leap ahead in technology and gain an advantage, and so it's not surprising that they might misinterpret or overanalyse some odd half-glimpsed detail. Maybe this fear derived from memories of WWI, when one side or the other would roll out a new scout every 6 or 12 months and rule the skies for a brief period? Whether it was institutionally-driven would be interesting to know, or maybe it was derived from pilots' memoirs or popular histories of the air war.

JDK

There's good points there, Brett. However I think there's a lot more aspects to it. For instance the 'denial' of the arrival of the Fw 190 as being 'Curtiss 75 Hawks' is the opposite to recognising or anticipating a new threat.

The He 113 was, of course, a complete German propaganda coup, backed by what I think of as inadequate British intelligence - being able to analyse and quantify what the Luftwaffe fielded seems to have been very poor until midway into the Battle when they were starting to analyse captured aircraft.

Brett Holman

Post authorMaybe they'd overcompensated after being wrong so often?