As I'd never been out west before, I allowed myself a couple of days after the Perth conference for sightseeing. First I travelled down to Fremantle, not far south of Perth.

...continue reading

As I'd never been out west before, I allowed myself a couple of days after the Perth conference for sightseeing. First I travelled down to Fremantle, not far south of Perth.

...continue reading

A belated Anzac Day post.

Willunga is a small town in South Australia, not far south of Adelaide, not far from the coast. It was settled by Europeans in 1839, only a couple of years after the colony itself was established. It was a farming area, cattle mostly, and slate quarrying soon became an important industry. By 1860, it had its own militia unit: the Willunga Rifle Volunteers (or Volunteer Rifles, or Willunga Company -- the name varies from source to source). Why did a small country town need a defence force?

There are two reasons that occur to me. The first is, obviously, for defence. South Australia is a long way from anywhere, even the rest of Australia, so it's hard to imagine anyone invading it. But turn that around: it's precisely because South Australia was so far away from anywhere that South Australians felt the need to make some provision for their own defence. As a colony, South Australia was ultimately defended by Britain. But neither the British Army nor the Royal Navy had any units stationed there: the closest would have been in Western Australia or New South Wales (or, later, Victoria): a very long way indeed before interstate railways began to link up in the 1880s. (And even then each colony used its own gauge. The states still do.)

...continue reading

The war artist is Eric Thake (1904-1982), and the family is mine, although only in the extended sense: Thake's grandparents, John and Sarah (née Prentice) Thake, were my great-great-grandparents. It was only a couple of weeks ago that my mother found this out. My paternal grandmother (who was born a Thake) did maintain that he was related, but how exactly was unclear, and his middle-class life in suburban Melbourne seemed a long way from her family on the Murray. But she was right!

Thake is a moderately important Australian artist: as one indicator of this, the Art Gallery of New South Wales holds 131 of his works in its collection. He worked in a number of different media: watercolours, photography, sketches, linocuts. In later years he even designed stamps, including a series to mark the anniversary of the first flight from Britain to Australia. He started out as a commercial artist in the 1920s, but also began to make a name for himself in less practical forms of art, including surrealism: in 1940, the director of the National Gallery of Victoria denounced Thake for being 'too modern'! Perhaps his modernity was why the Royal Australian Air Force selected him in 1944 to be an official war artist. He had already shown some interest in the technology of flight, for example in this surrealist work entitled Archaeopteryx (1941):

...continue reading

On my third day in Cornwall I avoided the usual tourist traps entirely, because I was in search of my ancestors' home: a tiny little place called Tremayne, which is towards Land's End, in the hundred of Penwith. To get there I caught a train to Camborne, then a bus to Praze-an-Beeble (no, really!), and then walked along a winding country lane with no footpath and some very high hedgerows. Luckily I didn't get run over, as that would rather have spoiled what was a beautiful day.

...continue reading

The grave of Pte John Joseph Mulqueeney, in Courcelette British Cemetery, Somme, France. He was killed on 17 August 1916 near Mouquet Farm.

I am extremely grateful to Steve John for providing me with this photograph.

This week, I was looking at the service records of some other family members who served in the world wars -- those that have been digitised anyway -- and as today is 'Straya Day,1 it seems appropriate to write a little about them.

...continue reading

It's exactly 40 years since the Battle of Long Tan, a notable feat of Australian arms during the Vietnam War. But I have a more personal anniversary in mind -- yesterday was 90 years to the day since my great-grand uncle John Joseph Mulqueeney was killed by an artillery round during the Somme campaign, on 17 August 1916. As I wrote a brief memorial about him last year on Remembrance Day, today I thought I would look at the online sources I used for that post.

The first thing to note is that the Australian War Memorial website is absolutely superb for researching family members who served in wartime. By entering a surname on their search page, choosing a war and specifying whether they were killed in action or not, you can obtain a wealth of information, including Red Cross records, embarkation rolls, lists of decorations awarded, and so on. There are also two important external links: one to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission for the location of graves (though the AWM link is actually broken at the moment), and another to the National Archives of Australia, where service records can be obtained (hopefully online, if not photocopies can be ordered).

In looking through these records, the big surprise was that Private Mulqueeney did not die at Gallipoli, as my family's oral tradition held. Upon reflection, the reason for this is obvious -- over the years, as the family members who could remember John themselves passed away, the succeeding generations assimilated fragments of his story into what little they knew of the war, and that increasingly came to mean Gallipoli. Unlike Gallipoli and in contrast to the situation in Britain, the Somme has little meaning for modern Australians. And in family history terms, having a relative who fought at Gallipoli has a cachet that is probably only second to having First Fleet convict blood running in your veins.

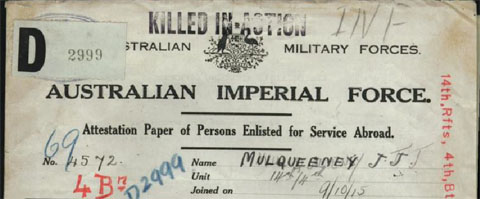

His service records were perhaps the most interesting, and sobering, find. Here's part of the attestation paper filled out when he enlisted. Note the bureaucratic scrawls all over it, and in particular the very final KILLED IN ACTION stamped across the top -- naturally, such a common occurrance merits a labour-saving device like a rubber stamp.

From his casualty form, we can trace his movements in the last months of his life. On 7 March 1916 he disembarked at Alexandria from the troopship Wandilla and on 29 March (presumably after further training) re-embarked, this time on the Transylvania, arriving in Marseilles to join the BEF on 4 April. He then presumably moved to the Australian depot at Etaples, where he remained for over two months: his group of reinforcements joined the 4th Battalion on 13 June. I'm not sure where the unit was then -- I'd need to check a unit history or war diary for that -- but it was another two months before he was killed, near Mouquet Farm. He was a well-behaved soldier, with nothing to mar his conduct sheet (where his character is recorded as "good").

John Mulqueeney's death added more pages to his service record than his life ever did. Six relate to the forwarding of his personal effects to his father, Timothy:

Writing Case, Tie, Key, Letters, Cards, Photo, 2 Pen Holders, Holdall, Housewife, 4 Brushes, 2 Combs, Scarf.

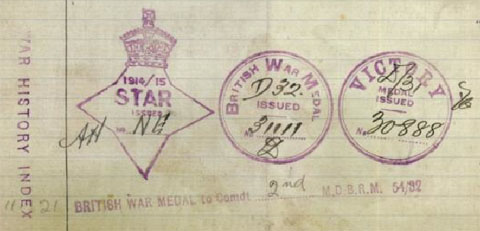

A receipt slip from 1921, to certify that (I think) his mother, Sarah, had received his 'Memorial Scroll and King's Message'. Stamps for his service medals: 1914/15 Star (presumably because he enlisted in 1915), British War Medal, Victory Medal.

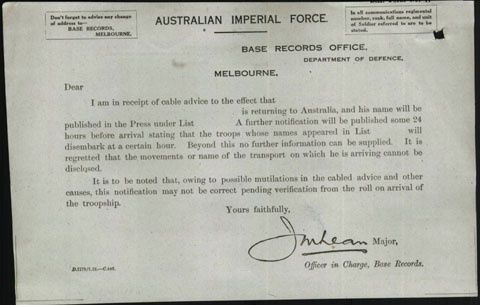

A positive reply to a family request for a photograph of his grave at Courcelette British Cemetary. Perhaps saddest of all, a form letter evidently for the purpose of informing his family which troopship he will be coming home on, never to be filled in, never to be sent.

Finally, there are the records of the Australian Red Cross Society Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau's enquiries on behalf of his family. They wrote to his comrades, asking for more information than the terse Department of Defence telegram would have provided.

We should be most grateful for any details you could send us concerning 4572 MULQUEENEY 4th Batt. A.I.F. and would also be glad iff [sic] you would add a short personal description, or any points that would sa tisfy [sic] his relatives that no error had been made.

There were six replies, including one from his sergeant. Pte. Hutchinson (himself recovering in the Eastbourne Military Hospital) provided the following information in December 1916:

Informant states that on Aug.17th. 1916, at the Pozieres Sector, a friend, Pte. McBride asked him to go with him into the next bay to see if "old Mul" [?] was alright as he did not think he had moved for a little time. Informant went, they found Mulqueeney dead, shot through the head, death must have been instantaneous. This was during the big bombardment. They buried him just beyond the bay, and informed the Sergt. Informant took some letters which he is sending to the Mother with details and also has pay book which he will forward to the right quarter as soon as he can do so.

That same month, Pte. Dickman wrote from Etaples:

He was killed at Moquet [sic] Farm about the middle of August. We were in the trenches. He was observing. I saw him killed by a shell, which burst near the parapet, and a piece hit him in the head. He belonged to IV Pl. A.Co. I knew him quite well. He was buried in a shell hole near by. A rough cross was put on his grave.

I hope that knowing how John Mulqueeney died, the return of his effects, the photo of his grave and so on, somehow provided some solace to his family. I can only imagine the pain they carried with them for the rest of their lives. My own sadness in examining these remains of his life can only be the palest (and somehow unearned) reflection of their grief. And of course, this was merely one, not particularly remarkable, death from a very bloody war. Scale all of that up by a factor of 10 or 40 million or so, and that's one huge reason why the First World War is still worth studying.

Today is Remembrance Day. Today I remember Private John Joseph Mulqueeney, of Tumut, New South Wales - my great-grand uncle. A labourer in civilian life, he enlisted in the 4th Battalion of the 1st AIF (Australian Imperial Force) on 9 October 1915, embarking for Egypt on 3 February 1916. His unit was soon redeployed to France, where it fought in the Somme offensive; in the middle of August it was involved in the attempts to capture Mouquet Farm, near Pozières. On 17 August 1916, Pte. Mulqueeney was looking out over the parapet when a shell landed in front of his trench, and he was hit in the head by a piece of shrapnel. He died instantly. He was 25 27 and, according to his sergeant, a 'good chap'. His fellow soldiers buried him in a nearby shell-hole, marking it with a rough cross, though his remains are now in Courcelette British Cemetery.

Lest we forget.

Image source: Australian War Memorial.