Spooked

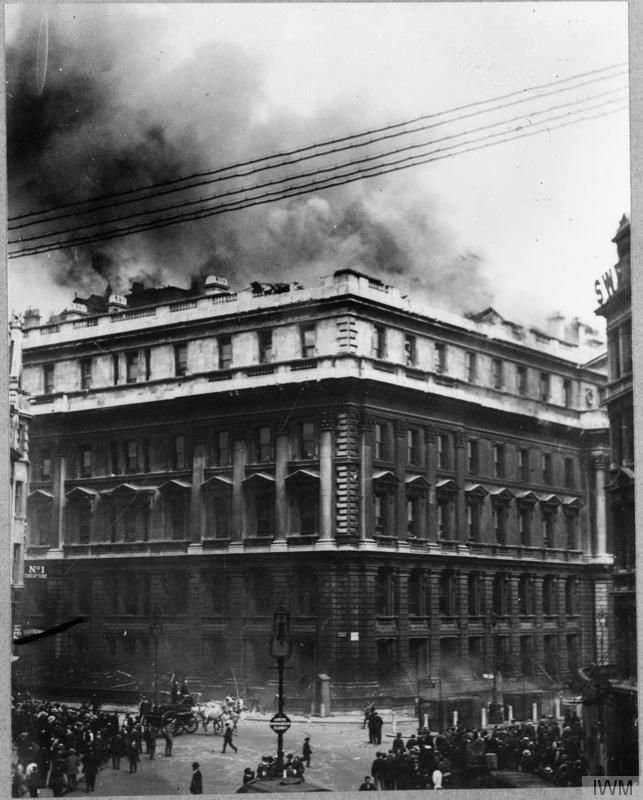

One of the fun things about historical research is finding something when you’re not looking for it. Alan Murdie, in his regular ‘Ghostwatch’ column in a recent Fortean Times, wrote the following: At Folkstone [sic], in 1917, candles in an air-raid shelter were mysteriously extinguished amid other poltergeist events. Natural gas from strata was blamed.1 […]

![German propaganda poster with a vibrant and striking image depicting swarms of British aircraft bombing an industrial site to illustrate the following quote, by British Labour Leader Johnston Hicks [sic], which appeared in the 'Daily Telegraph' on January 3rd 1918: 'One must bomb the Rhineland industrial regions with one hundred aircraft day after day, until the treatment has had its effect!’](https://airminded.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/artv05099.jpg)