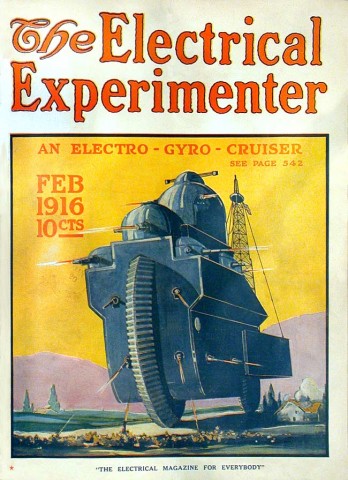

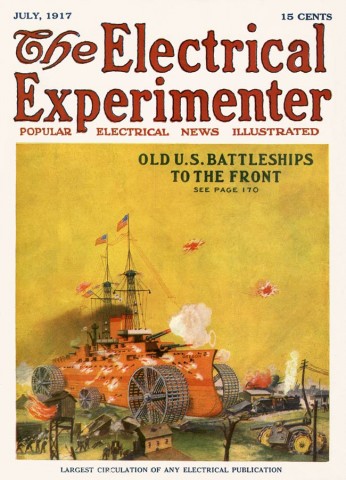

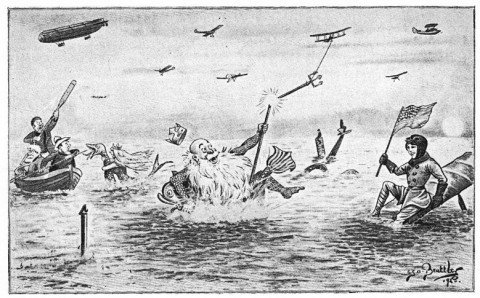

The Electrical Experimenter was an American science magazine, founded and edited by Hugo Gernsback. These covers were published during the First World War, and illustrate ways in which science could be used to create new weapons and new defences. Many of them are just a little far-fetched, such as the land ironclad shown above.

Or this electro-gyro-cruiser.

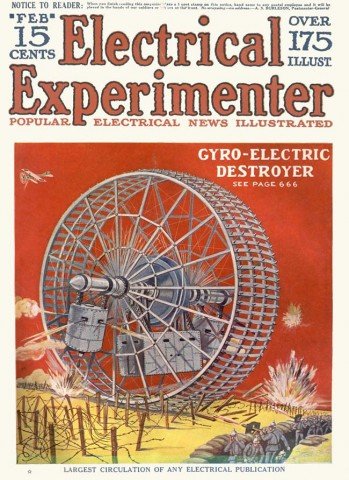

Not to be confused with the gyro-electric destroyer, of course.

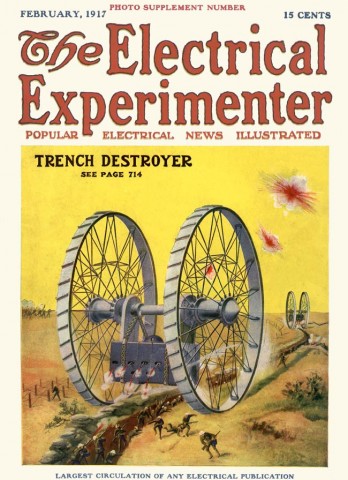

The trench destroyer is not quite in the same category of improbability, since the Russians did test something similar in 1915.

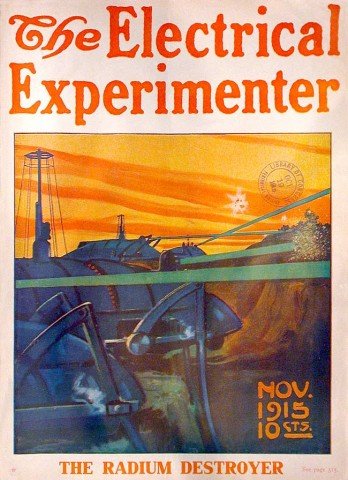

Radium destroyers aren't quite so imposing, even walking ones, but would seem to rely on more advanced science than the mechanical monstrosities above.

And we still haven't come up with anti-gravitation rays.

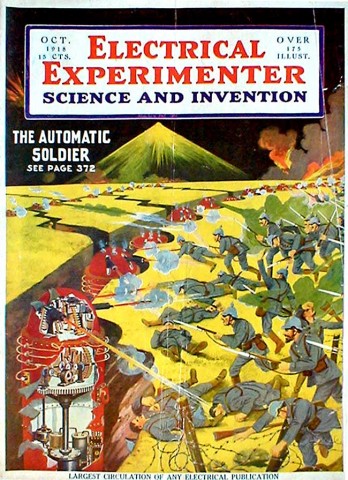

Or automatic soldiers, though we're getting closer.

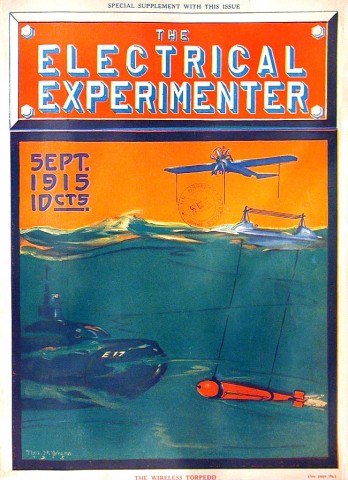

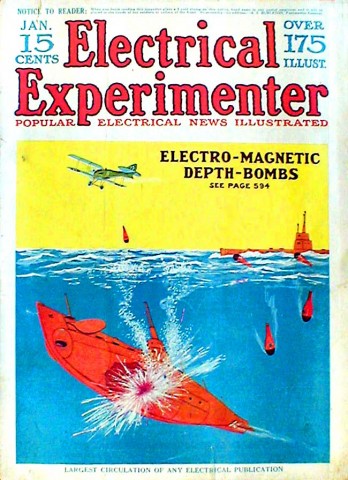

The problem of the submarine seems to have stimulated less fanciful (if still unworkable) ideas. Here is an anti-submarine torpedo controlled by radio.

This looks like some sort of boom which causes torpedoes to explode before reaching the ship.

Here, intense searchlights blind a U-boat's periscope.

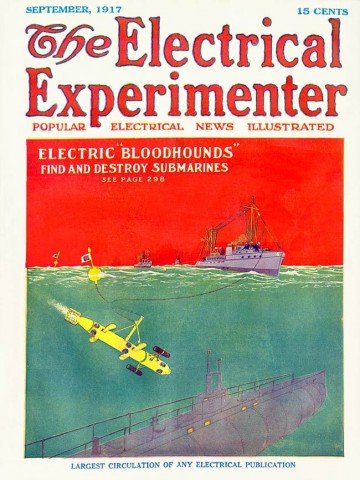

A homing torpedo to seek and destroy submarines.

Magnetic depth charges, triggered by a submarine's magnetic field.

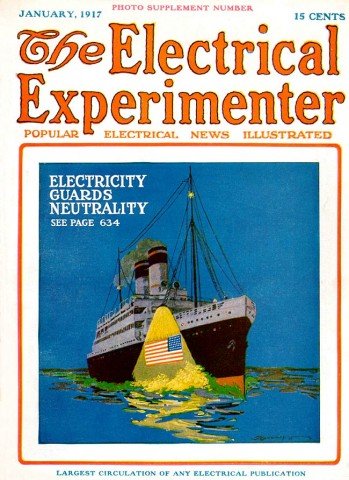

Even the simple use of lighting the side of US merchant vessels could ensure that German submarine commanders would see the large American flag painted on the side, and so avoid firing at a noncombatant. Hence 'Electricity guards neutrality', a great title for a paper if ever I heard one.

Admittedly, this post is partly just an excuse to display some of these wonderful magazine covers. But more seriously, they do display a remarkably vivid imagination when it comes to deploying science and technology in war, an imagination which generally seems to be lacking in contemporary British periodicals. As far as I can see, English Mechanic, Practical Wireless, Practical Mechanics and Wireless World were much more staid than Electrical Experimenter in terms of their visual style. It could be argued that Gernsback was unique, but in America his style inspired, in different directions, the pulp SF magazines of the 1930s and visually arresting science magazines such as Modern Mechanix or Popular Science. Where were the British Gernsbacks?

Image source: MagazineArt.org.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Chris Williams

Wells. As in 'Wells was one of them', not 'the were all in Wells.' Most of that Gernsback lot is various re-mixes of the 'brain beats brawn' theme of _The Land Ironclads_. But don't ask me about the visual language, though - I don't know of anything in the UK that approached this.

John Ptak

I love these ideas. Or the images of them. It would make an interesting phyz class to figure out what sort of powertrain an ironclad would need to make its way around on land and compare it to the massive engines needed to push the beast around floating in water. And what happens if the land ironclad got stuck? I like the wheels.

Erik Lund

This is a great subject that I've wondered about myself, but it seems to me that you'd have to start with a level playing field in the sense of comparing weeklies to weeklies and monthlies to monthlies, or at least have an argument for discounting the differences.

Hmm... is _Aviation Engineering_ more like _Aviation_ than is _Flight_? _I_ could do that comparison. I'd just need a metric...

Pingback:

Notional Slurry » links for 2009-11-29

Brett Holman

Post authorChris:

Yes, Wells for the non-visual side of things, and Wells was not without imitators himself. But he was far less optimistic than Gernsback that technology was a panacea.

John:

Yes, the battleship-on-wheels is my favourite! It's just so crazy it might work ... actually, no.

Erik:

Metrics would be nice, but having access to full runs of these magazines would be nicer!

Ted Samsel

This is where Bruce McCall (illustrator for the National Lampoon/ New Yorker) got a lot of his schtick from. Weren't we supposed to have antigravity by 1995?

Jakob

I'm currently re-reading Don MacKenzie's 'Inventing Accuracy,' and now whenever he uses the term 'gyro culture' I'm going to think of GYRO-ELECTRIC DESTROYERS! Although I suppose a Trident D5 could be described as one without stretching the truth too much...

Chris Williams

"Giant Radio Robots Play Ice Hockey at 300mph" - best Bruce McCall headline ever.

John Shepherd

WRT the Trench Destroyer. A smaller, but similar contraption - propelled by rockets mounted on the rims of the wheels - was proposed to deliver a large explosive charge against the fortifications of the Atlantic Wall in WWII. Called the _Great Panjandrum_, several versions were actually built and tested. It turned out, however, to be almost as dangerous to those who operated it as it would have been to the enemy.

Pingback:

Airminded · The superweapon and the Anglo-American imagination — IV

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks, John. It turns out the name was chosen by my man Shute!

Robert

Nice material. The ironclad landships reminds me of a book I read on the US Coast Artillery Corps during the First World War. The author made sure to inform readers that the CAC did float Fort Monroe over to the Western Front.

JDK

They certainly saw no limitations to electrical experimentation, did they?

While there's no real world correlation, it's worth noting that the the Tank was the brainchild of the 'Landships Committee' and that the rhomboid shape of the early tanks was arrived at to develop a trench-crossing 'footprint' that was derived to some extent by just using the critical lower arc of a giant wheel*.

So they were onto something. Just a very, very big gap between idea and implementation!

*Italicised because of the "dah de dah" ominous music requirement.

Ross

Brett here is a picture of a model made by Steve Zaloga of the Russian Nepotir.

http://www.missing-lynx.com/gallery/other/tsar_szaloga.html

Quite a large looking vehicle.

Brett Holman

Post authorVery impressive, thanks.

JDK

If I saw that coming I'd be torn between sensible running away and staying to watch the bits go 'twang' one piece at a time, with more eccentric wobles as it wound down... rather like a Professor Branestawm gyroscope.

Brett Holman

Post authorRun away. Always.

Pingback:

Airminded · Positive and negative airmindedness