[Cross-posted at Revise and Dissent.]

Here's a confession: I don't really get Guernica -- the painting, that is, not the event (which is why I haven't mentioned it in this series until now). I understand that it's a passionate reaction by a great artist to the tragedy unfolding in his own country. It's physically imposing, rich in symbolism and, by now, a part of history itself. I'd love to see it one day. But what I don't get is how, and why, Picasso's Guernica came to be seen as a more powerful reaction to the coming of total war than this:

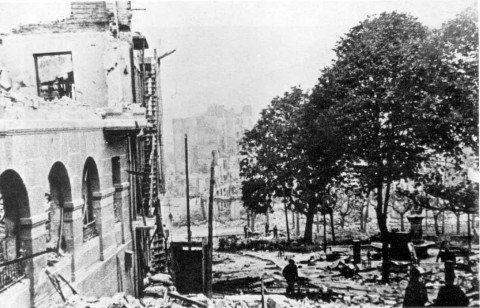

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

Or this:

To me, it's not, but perhaps I'm irredeemably literal. Why is Guernica such a recognisable image, and these so unfamiliar? Is art more powerful than reality? (Not that photographs aren't constructed at all, but they do record the effects of photons which were actually reflected from the ruins of Guernica, or emitted from the flames which consumed it.) Are the photographs of Guernica '37 devalued by their similarity to post-raid pictures of London '40, Hamburg '43 and Tokyo '45? Feel free to educate me in the comments!

The images of Guernica after the air raid are from Wikipedia, though from a user page, not an article. A couple have been deleted from Wikipedia, but I managed to find them here and here.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback:

Respectful Insolence

Ali

photos of the devastation of war aren't a reaction per se, but rather a representation. picasso's piece is both. if you were to ask which is simply a more powerful image, i think most people would agree that the photos are.

Ali

(see also my comment on orac's blog)

Skeptyk

Screaming horses, crying people, eyes of wild terror, the dead baby. One may project these onto the photos Brett posted, or not. Picasso does not give you choice. His skill, the scale ("Guernica" is BIG), and the subject, all are part of the power.

The painting, unlike the photos, is of people, and people respond to the suffering of people. As shocking as the photos after air raids are (and they are) they are not of people. We must add the people in our heads, based on knowledge and imagination.

All the photos I saw of air raids paled in contrast to the stories told by friends who "survived" the Dresden bombing, running, running into cellar restaurant to find piles of asphixiated dead, running past charred dead and dying people in the streets, two children running, their families lost...

...or when Michio Kaku told me of his relative (uncle?) who "survived" the Hiroshima bombing...

We are probably "wired" to react more viscerally to individuals in pain, to others with faces, rather than in the abstract. It is a human, perhaps a civilized, ability to be able to know understand harm to others at distance of time and space and at scales uncommon in a lifetime. Vesuvius killing Pompeii and the Lisbon Earthquake...huge and rare, and natural disasters, such things were in most of our history. In the past century we figured out how to do that kind of damage ourselves.

Even ancient gorgeous buildings bombed to ruins, even the awareness that people lived in - and many died in - these buildings, will not effect most people as strongly as will that dead baby in "Guernica".

Skeptyk

Yes, I found you via Orac.

I looked at some of your previous posts on Guernica, and thank you for posting the original reports of the day after. Those and the photos closed the distance in time. Maybe because I am old enough to have black and white photos from my childhood, B&W does not seem ancient, but it occurs to me that modern folks, used to full color moving images, may also not be as moved by the air attack photos as they are by the painting because B&W photos do not feel real to them. If they see color photos of Beirut from decades ago or New York in Sept., 2001 or Baghdad today, those look real, but most young people in the US (where I am) may have seen more cinematic recreations of newsreels than actual newsreels.

Fiasco da Gama

I think it's a lot simpler than that. Picasso's Guernica was exhibited at the 1937 World's Fair in Paris, as the centrepiece of a building's worth of pro-Republican information and propaganda.

I don't think it started out as such a general anti-bombing painting, so much as a specifically anti-Nationalist, anti-Franco painting---a rather more popular cause in the era. After all, as Mayor Quimby might have said, those could be anyone's bombs in the photographs.

Also, on 'getting' the painting: it's not just pretty big, or imposing, it's deliberately fucking enormous. That's too easy to overlook, but it quite literally takes a whole room of the Reina Sofía.

Chris Williams

When we want a picture of the Blitz, we get the one of St Paul's or the (?faked) one of the Heinkel over the docks. This is because it's obviously London. Pictures of ruins are anonymous, and they all look the same: in fact, in the 1930s context, they look like Flanders. So the best image for Guernica has become the painting, because unlike the ruins, we know whre it is. Via the same process, the main gate at Auschwitz has become the number one image to exemplfy the Holocaust.

wil

Perhaps you are "irredeemably literal" -- hard to be certain from one post.

For what it's worth, great art IS more powerful than reality. The artist intentionally uses symbols to manipulate emotions. Color (or its absence), scale, faces -- it all serves to evoke emotions. Photographs only manage to achieve that result far less frequently; usually, untouched photos of ruins can only convey the sense of devastation and loss (and often only if corpses are present). Otherwise, it's just bricks and mortar, concrete and steel. They don't bleed. They don't scream. The don't die.

Above all else, Guernica speaks to me of death. The photos you used above don't.

Here via Orac, in case you were wondering.

TheBrummell

I'm with Brett on this one, perhaps I am also "irredeemably literal". I don't "get" the painting as well - the photographs above provoke much more reaction in me than the painting.

The weirdly abstract forms, the strange juxtapositions of objects... I just don't find it emotionally powerful so much as confusing. Perhaps I am not capable of appreciating great art in the way that others can. Or perhaps I just don't like Picasso's stuff.

The photos, on the other hand, starkly show the scale of the destruction of a city. Yes, the city is fairly annonymous, but that's part of the power - I can easily imagine the same level of destruction visited upon other cities that I am personally familiar with. The appearance of corpses, or of stricken people showing the emotions on their faces, some visual representation of what Skeptyk was talking about regarding Dresden et al., would certainly enhance the emotional power of those photographs. But their power is not zero without such personal images.

Fiasco da Gama said: Also, on 'getting' the painting: it's not just pretty big, or imposing, it's deliberately fucking enormous. That's too easy to overlook, but it quite literally takes a whole room of the Reina Sofía.

I have never seen the original. Perhaps if I had, and seen it at its true size, I may feel differently. Other very large paintings I have seen did seem to pack more visual 'punch' than smaller copies. Does Guernica ever get sent to other institutions for shows?

car

(Came via Orac)

I think they are powerful in different ways. The photos show the actual destruction of physical things; the painting shows the destruction of humanity. What strikes me most about Guernica is to sit and think about the sorrow and anger in Picasso as he was creating it, the emotion behind every brush stroke. Even though it's representational, it's more human.

I have to admit, though, every time I see/hear of the painting, I think of a line from the short-lived animated series The Critic: "Take that, Guernica!"

Fiasco da Gama

Rarely if ever, TheBrummel. Not just for the technical problems of moving it, but also for the political reasons that Spain is still coming to terms with their Civil War history.

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks, everyone, for your input -- I may not get Guernica but I think I get why others do! For the record, TheBrummell pretty much describes my own position: the painting is distracting, the photos are stark. The painting is just one man's reaction to Guernica, the photos show what he was reacting to. Although there are no bodies in the photos, we can probably assume that the destruction in each one correlates to the destruction of one or more innocent life: there's real suffering in them, not an abstract representation of such. That's my reaction, and I don't put it forward to say, "well, geez, you're all just wrong", just to explain where I'm coming from and why I was interested in hearing different views.

By the way, I have previously posted a post-air raid photo which shows a dead body, which I think is terribly affecting: here, if anyone is interested (it's not gory, just sad). It was taken in Barcelona, though, not Guernica.

Skeptyk and Fiasco da Gama make very good points about the sheer enormousness of Guernica (there's a photo showing the scale here). But on the other hand, since not many people do actually realise how big it is (particularly since relatively few people have actually seen the real thing), that can only be a small part of the explanation of its power.

I'd also have to take issue with Fiasco's statement that

I think that overstates the popularity of the Republican cause at the time: there was a significant segment of opinion which thought that communism was a greater danger than fascism. But I know it understates the degree of fear and apprehension about bombing (whether by "them" or by "us"), since that's what my PhD research is about :) You're right, Fiasco, that I glossed over the original anti-Franco meanings, but certainly as time passed that was forgotten anyway, and for most I would say it's an anti-war painting now.

Ronan Cunniffe

The way to "get" Guernica is definitely to go and see it - but before you go in to the painting itself, to spend time on the sketches Picasso made in preparation (also in the Reina Sofia). This is an astonishingly clarifying exercise - for me anyway, it transformed the painting from confusing to .... profound is probably the best word I've got.

Jack

I've been watching this debate with great interest from the sidelines. I, too, am always wary about generalizing from my own, subjective responses to works of art. A lot of visual art I simply don't 'get' (even though I really wish I did).

So all opinions above are, of course, utterly valid. But, having seen the sketches in the Reina Sofia, I'd agree with Ronan. It really is a matter of emotional response rather than semiotic analysis. I suppose it appeals to an 'act of faith' or leap of imagination rather than a 'reading'. Maybe that's the key difference between painting and photography, IMHO - not that the latter is not also 'art'.

But I think iconography is the key. When you absorb the extent to which 'Guernica' symbolizes the opinions, experiences and collective agonies (and I don't use that term lightly) of a substantial sector of the Spanish population (even to this day), then it ceases to be 'merely' a painting. I was completely swept away by that culture for many years, so the painting has many additional layers of adopted resonance for me.

Maybe whether 'we' get it or not is not the issue at all. What matters is why 'they' get it. We could debate who 'they' are, of course. But I suppose that's the point at which an artefact becomes a memorial/commemoration/emotional rallying point. Personally, when responding to 'Guernica' I'm now responding to a monument, not a painting. I don't think, with any amount of effort, I could now strip it back to being 'just' a painting.

But hey - you military-ish myth-and-memory types know far more about those matters than me. And, of course, that's the point of art - it is transformative, has no fixed meaning and we can debate it forever. Which is nice.

Brett Holman

Post authorYeah, well it's alright for all you European types to say "you simply must go and see it" but about the only way I could live further away from Madrid is to move to New Zealand!

Point taken though, I can understand that much of its power as a work of art derives from Picasso's passion and anguish, and that it has become entangled in history itself. But then again ... that's partly why I'm wary of it. He was just one man, and his painting is the reaction of just one man. As an historian I should be wary of relying upon just one source, and yet Guernica has come to stand for Guernica and much else. Who needs to understand what actually happened at Guernica, or what people felt after Guernica, when we've got Guernica to look at?

Having said all that, Guernica was exhibited in London just as the Munich crisis was ending, and I'll be keeping an eye out for how British artlovers reacted to it at the time ...

david tiley

An image using realistic elements is not just an image; it is a narrative, a story plucked from the surface.

Hence we are moved by one photo of a dead child, but not another.

Sounds obvious, but in documentary it is an important issue. Not enough to record; it is necessary to record artfully.

One of my 'favourite' bombing images is this.

Tension and intention.

Brett Holman

Post authorI can see that, but to me these images have a starkness that goes beyond any need for composition or artfulness. Possibly it's just that I spend to much time thinking about bombed-out cities ... I can easily supply the narrative and context myself, whether or not it's provided within the frame.

david tiley

That is the thing, isn't it. You do supply the narrative - just as the alerted viewer does the same to Guernica. Note that people say they get more from the painting if they have seen the sketches.

Particularly in a fast moving medium like television, knowing what the audience shares is very important. And is wrong again and again. i'm gone every time some breathless narration announces the beginning o fWW2 as if it is a surprise to the viewer.

Something else - Guernica is big. If you took your photos above and expanded them at very high resolution to life size, they would be completely crushing to the viewer.

And if you could add an image of that child alive with its mother, people would weep. Even though it is black and white.

Gavin Robinson

According to Wikipedia (which could be wrong, and the fact that I have to rely on it here shows that I don't really know what I'm talking about!) Picasso lived in France throughout the Spanish Civil War. Many people pour scorn on Jessie Pope for writing poetry about the First World War when she hadn't experienced combat. I don't see that as a problem, because you can be affected by wars even if you're not at the front line or being bombed, and it's legitimate to think that the bombing of Guernica was a bad thing even if you didn't get bombed yourself, but has anyone criticized Picasso for painting something that he didn't witness? If not why not? Is it because he had the "right" (ie anti-war) view whereas Pope had the "wrong" (ie pro-war) view?

david tiley

I guess we could call this asymmetric. Somehow it is less ikky to use art to complain about other people being slaughtered when you weren't there than to use art to encourage other people to be attendant on a slaughter when you weren't there.

You can't accuse Picasso of hysteria - indeed the fact that he wasn't there makes the work less passionate. Because no-one who hasn't run through the flames of a burning city can completely comprehend what it is like. And then I don't believe you can reproduce it.

It is all beyond human communication, and maybe beyond comprehension for the people who were actually there.

Even my parents, who spent bits of the Blitz huddled in their family Anderson shelters, make no attempt to describe it. I don't think they can. I don't think they even retained it.

Brett Holman

Post authorI thought the scorn for Jessie Pope was as much due to the fact that she wrote such dire poems :D

Part of the asymmetry might be that specific anti-war messages are easy to interpret as generic anti-war messages -- they detach from their original context -- whereas pro-war messages remain attached to their original context. Imagine if Picasso had painted some rousing pro-Franco, let's-kill-the-commies thing instead. There aren't that many people these days who believe that war is inherently a good thing (or are there?), it depends on the reasons why it was fought. Once those reasons are forgotten (or rejected), recede into the past, the artwork would lose its power to move the spectator. Whereas anything with an anti-war message is assimilated to all wars, past, present and future, whether actually relevant or not.

Or it could just be that art criticism is not my thing and I have no idea what I'm talking about :) After all, lots of people still seem to like Jessie Pope, dire poetry and all ...

Gavin Robinson

I have to admit that if I was forced to read war poetry I'd rather read Owen than Pope, but you could turn it round and suggest that Pope's poetry is dismissed as being "bad" because it supports the "wrong" point of view, while Owen has been elevated to the canon because he has the "right" view. How do you objectively measure the aesthetics of poetry? If you can, are Jessie Pope haters applying the criteria honestly and objectively? I'm sure we could find some right-wing people who think that Picasso's paintings are bad art, but again you'd have to suspect that political ideology plays a part in their judgement, and it could also be that people with different political opinions also have different criteria for judging the "quality" of art, even if the message isn't obviously contentious.

It's good point that anti-war art easily makes the transition from specific to general. The hypothetical right-wing critic of Guernica might say "you can't even tell what it's supposed to be". In a way that's true. Several people have made convincing comments here about the emotional impact of the painting: you can tell that something terrible has happened. But what? There isn't much internal evidence in the painting to tell us that it represents the bombing of Guernica in 1937. That all comes from context: you have to know that it's called Guernica and know what famously happened at Guernica. If you showed the painting to someone who knew nothing about it, and told them it was called "Auschwitz", would it have the same impact? Or an even greater impact? But what if it was called "The Harrying of the North"? Would connecting the image to something that happened in the 11th century and which most people have never heard of diminish its impact?

(btw it's a good thing you linked to BODITT to explain who Jessie Pope was. The Wikipedia page on her is so spectacularly bad it's quite funny!)

Brett Holman

Post authorI think it must have. And as this thread has shown, understanding how Guernica came to be enhances its impact for some people. So the original context is not unimportant for anti-war art: sufficient but perhaps not necessary.

It's not quite pro-war but Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will seems pertinent here -- the classic question of whether it can be considered as great art despite its cheerleading for fascism. But if you knew nothing at all about Hitler then the problem wouldn't arise ... you could simply appreciate the visuals and the natty uniforms. But in this case, we (whoever "we" is) can't let the film detach from its context, we resist doing that. So if it is to be appreciated as great art, then it seems we must do so while remaining very aware of the intent behind it.

Pingback:

Airminded · Guernica, mon amour