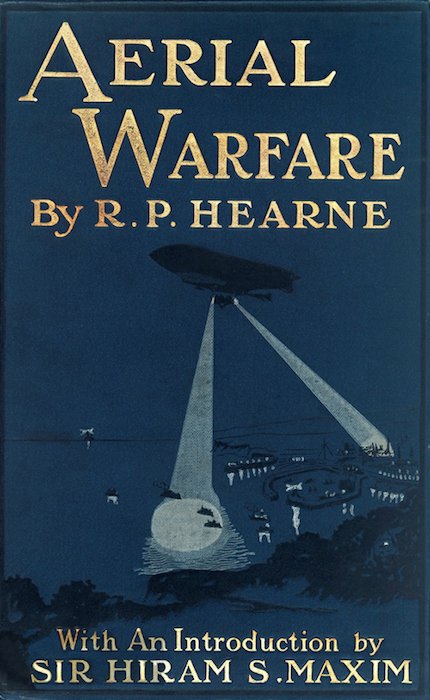

Repost: Secret Zeppelin bases in Britain — I

[Part of a celebration of Airminded’s 10th anniversary; originally posted on 6 September 2014. The start of my investigation into rumours of, well, secret Zeppelin bases in Britain in 1914, which continued here and here, and concluded here. And will eventually be published somewhere.] On ABC New England last week I briefly mentioned rumours of […]