Breaking the tyranny of distance revisited — I

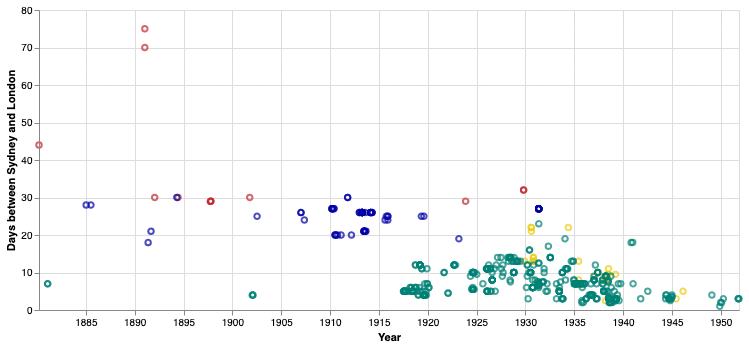

Nearly four years ago, I wrote a post about a software project Tim Sherratt and I were working on for Heritage of the Air called hota-time. Briefly, the idea was that hota-time would extract and then plot travel times between London and Sydney mentioned in Trove Newspaper headlines, as a quantitative way to gauge the […]