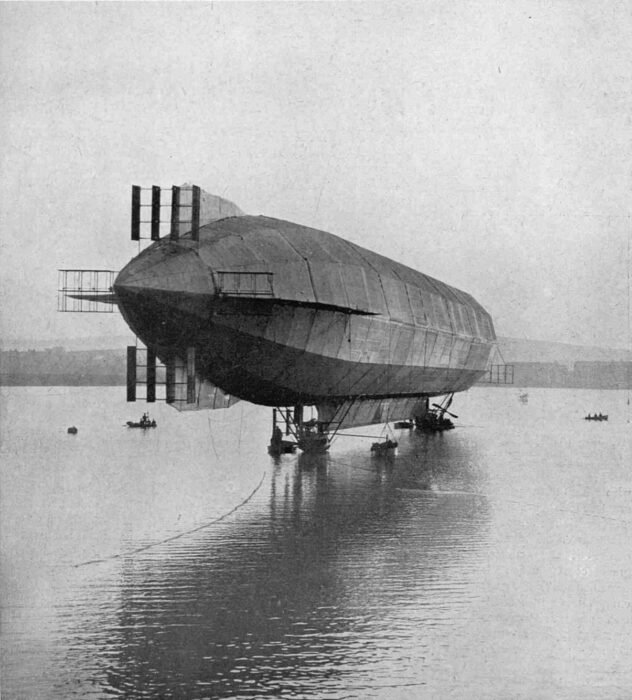

The mysterious flying machine of the mysterious Señor Alvares — I

A few weeks back, @TroveAirBot found a short article from the Port Lincoln, Tumby and West Coast Recorder entitled ‘Dropped From the Clouds’: A balloon which ascended from the Welsh Harp, Hendon, on October 14 [1904], carried with it into the clouds a large flying machine. As no one was in the car of the […]