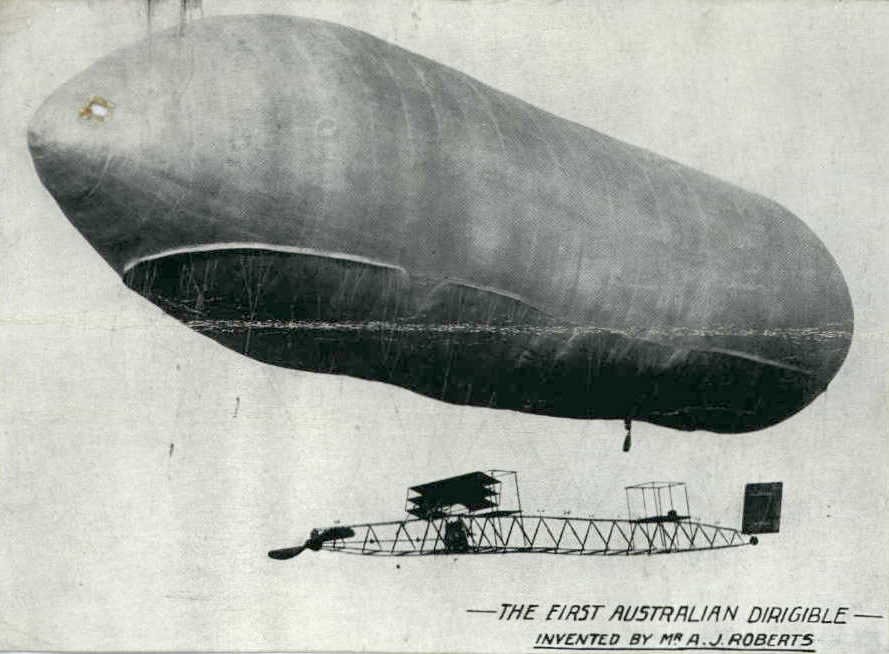

The Melbourne balloon riot of 1858

In the rather enjoyable Falling Upwards, Richard Holmes spends most of his time discussing the history of ballooning in Britain, France, and the United States. However, he does briefly talk about the first balloon flights in Australia: In 1858 the British balloon the Australian made some startling flights over Melbourne and Sydney. There was a […]