Friday, 30 September 1938

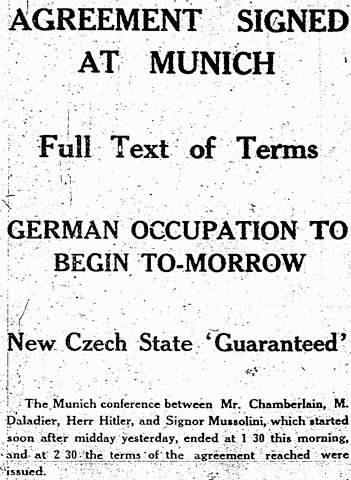

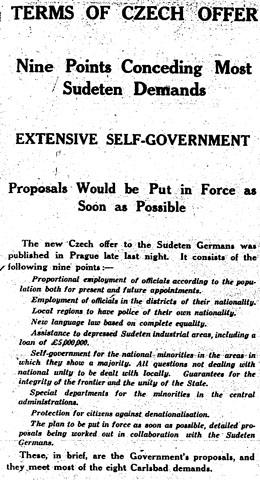

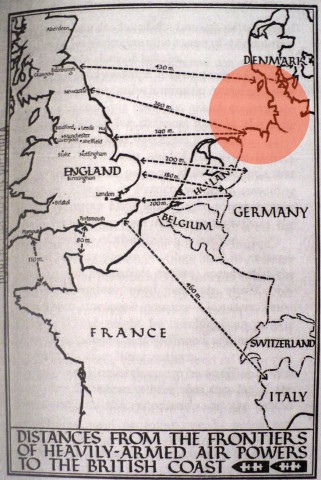

The hopes which were raised yesterday by the announcement of a four-power conference at Munich appear to have been justified (Manchester Guardian, p. 11). An agreement has been reached between Britain, Germany, France and Italy that the Sudetenland will be transferred in stages to Germany between tomorrow and 10 October. The installations in these areas […]