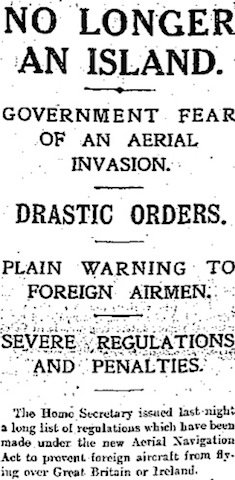

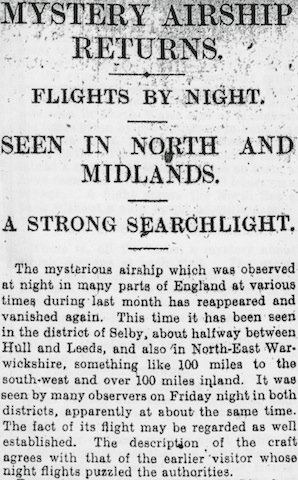

15 minutes of relevance

‘In the future, every historian will be relevant for 15 minutes’, as somebody once said. Here’s my 15 minutes, an interview with journalist Connor Echols for Responsible Statecraft on the parallels between the 1913 phantom airship panic and the 2023 spy balloon panic. As I’ve been busy with other things and have had to watch […]